Great Talent, Little Money, 1863-1879

Halifax in 1863. Opening of Dalhousie College. James Ross and his five professors. Charles Macdonald. James De Mille. Curriculum of the 1860s and 1870s. Dalhousie’s students. Faculty of Medicine, 1868-75. The University of Halifax, 1876-81. Penury.

The afternoon of Tuesday, 10 November 1863 was overcast; the wind from the northeast seemed to make the old wooden houses of Halifax huddle together as if for warmth. The grey smoke from the chimneys was blowing out toward the grey sea; there would be snow before morning.[1] Dalhousie College was opening once more, for the third time.

The half-century-old grey stone building on the Grand Parade looked out upon a Halifax slowly expanding and improving. Fire hastened the process. Granville Street was devastated by fire in 1859, and it was then rebuilt in stone, a streetscape that is still attractive. The harbour’s forest of masts and yards was bigger, as were the wharves and the warehouses behind them. Halifax was still very much a military place, and it showed in the red uniforms of the British soldiers, in the blue of the navy, enjoying, or enduring, their lives in the most important military and naval station on the northwest Atlantic.

It was still dominated by the Citadel. The British army had started rebuilding it in 1828; it was at last finished in 1860 at a cost of £242,122, double the original estimate. After having strained the abilities, and as one historian suggests, the sanity, of a generation of military engineers, the rebuilt Citadel was rendered virtually obsolete by technology, by the hitting power of the new, rifled artillery. Few military men were fully aware of that yet, and the Citadel would remain occupied by British troops until 1907.[2]

Hugo Reid said in 1861 that it was the army and the navy that kept Halifax alive. While that was partly true, Halifax was no longer so dependent on military expenditure, although it would profit from wars for many a year yet. Reid suggested that the greatest danger to the British army in Halifax was not the enemy, whoever they might be, but something more insidious and longer lasting: Halifax daughters. “The merchants are rich, and their daughters are fair, and the mingled charms and dollars have a powerful effect on her Majesty’s Service.” In summer there were those delightful picnics and excursions in the environs, which were followed, often enough according to Reid, by a very old church service with the lines, “Who giveth this woman to be married to this man?”[3]

If they survived those dangers, the soldiers and sailors found Halifax much like other garrison towns. Occasionally angry at being victimized by bad rum and bad women, they would break out in frustration, as they had in 1838. There was an even bigger riot in 1863, a week before the Dalhousie bill was given second reading. Some soldiers were beaten up in a tavern on Barrack (now Brunswick) Street, so the soldiers took their revenge by setting fire to the place. Rioting broke out and two nights later some three hundred soldiers armed with sticks and slingshots took possession of the downtown streets for over an hour. Finally the military authorities from the Citadel brought things under control. The local newspapers were severe on the rioters, but the Presbyterian Witness suggested that the soldiers had over the years been mostly peaceable, that the cause was “the mean and miserable civilians” who were to blame, drugging and poisoning the soldiers with bad rum. Indeed, some strange concoctions were brewed up in those grim houses just two blocks above Dalhousie College.[4]

Edmund Burke once described the court of France before the Revolution as a setting where “vice itself lost half its evil by losing all its grossness.” That was rarely true in Victorian Halifax. It was the theme of an editorial in the Presbyterian Witness, unhappy over the desecretion of Halifax’s Sunday by military and naval bands. Music was bad enough on such a sacred day; the tunes they played were much worse, jocular airs too often, with highly unsuitable verses. “Pretty employment this…! Pretty preparation this for eternity!” It also descanted against Halifax theatres. The British Colonist replied that the Presbyterians seemed to be a group who enjoyed sullen hatred of anyone outside of “their own sanctimonious and hypocritical society.” After all, said the Colonist, the Queen went to the theatre, and often. To which the Witness replied, “If the Queen frequents theatres the more’s the pity!” It was not alone in its Puritan views. The Provincial Wesleyan was upset with the new dance that had been imported from wicked Europe in the 1850s, the waltz, that had been taken up in Halifax. The worst of it was, young ladies who ought to have been repelled by its lascivious and seductive rhythms seemed willing, recklessly, to enjoy it.[5]

Halifax in the 1860s, with grog shops and taverns everywhere with plenty of patrons, was anything but a staid place. In the view of some religious papers, it could have stood a deal of starching. Temperance movements had been steadily gathering strength since the 1840s, and it was not difficult to understand why. One could hardly walk a few hundred yards in Halifax, complained the Witness in 1856, “without meeting a staggering ‘Crimean hero!’ – and very frequently these heroes are to be seen lying full length in the gutter or on the muddy street.”[6] No one could safely allege that Halifax was puritan; there were newspapers ready to try to make it so but it was uphill work.

Dalhousie College Opens

Dalhousie College was fairly in the midst of all of this. Its first concern was to shake off the dust and the mice of the past four years. The Morning Sun called it a “mouldering memorial” to Lord Dalhousie, hoping, despite that, it might turn into a provincial university whose professors were, for once, “up to their work.” Save us, it said, from another sectarian college, with its “interminable propagation of polemical divinity.” There was still plenty of that; Dalhousie would open amid the burgeoning antipathy of the religious papers, especially the Methodist and Baptist ones; even the Anglicans could not resist pointing out how Dalhousie could never be the provincial university “so long as the institution at Windsor retains the Royal Charter which so long ago constituted it as the University of Nova Scotia.” Nor was there much disposition on the Dalhousie governors’ part to make it a triumph; Dalhousie’s opening was low key, as befitted a college whose history had been, as the chairman remarked, “a list of failures.” In 1863 Dalhousie confronted considerable opposition. As James De Mille was later to remark, it started “without prestige, but on the contrary with a past history of failures… and there were not wanting those who prophesied a new failure.”[7]

Nevertheless, on that November afternoon the east room of the building was crowded, so much so that the reporter for the Morning Chronicle had no room to make notes, and recorded what he heard by memory. The proceedings were opened by Major-General Sir Charles Hastings Doyle, administrator of the province in the absence of the lieutenant-governor in England, and commander-in-chief of the British troops (and militia) from Bermuda to Newfoundland.

Sir Charles presented an olive branch to the phalanxes of religious warriors. “I am informed,” he said, “that this College will, in no respect, be hostile to the other Educational establishments in the province.” He, too, mentioned failures. Dalhousie College had

hitherto failed to obtain the patronage of the public; but I sincerely believe that the steps now taken to obtain Professors of high repute, and the exertions which have been made to remove the causes which have led to previous failures, success may attend its future efforts; and I trust it may turn out that the retrograde movements which have occurred have been simply the reculer pour mieux sauter. Let aucto splendore resurgo be its motto henceforth.”[8]

The chief justice, William Young, chairman of the Dalhousie Board of Governors since 1848, gave a history of Dalhousie, rehearsing its failures. Yet, he said, “its funds had not been diverted from their legitimate object, but were yet available to commence with, [and] they had a fine building in perfect order.” The new principal, James Ross, who followed Young, felt he had to enter a caveat to that point. Whatever the exterior may have been, the building was deficient in interior accommodation. There was no room suitable to perform chemistry experiments, and precious little apparatus to do them with. Perhaps the citizens of Halifax could make donations that might help remedy some of these more patent deficiencies. He hoped that the Law Society of Halifax would consider soon establishing a chair in law, and that a medical school would not be far behind. Lectures began at ten o’clock the next morning, the first students walking across the Parade through the light snowfall.

Dalhousie College in November 1863 was an experiment. No one quite knew if it would work. Students came, but much of its future depended on its staff, and their reputation had yet to be essayed or developed. It would have to make its own way by its own virtues, whatever those might turn out to be. The first motto of Dalhousie, appearing on the first Dalhousie Gazette of 1869, began with the word “Forsan” (Perhaps). It was from Virgil’s Aeneid, Book I, line 203, “Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit” (Perhaps the time may come when these difficulties will be sweet to remember).

The following year a more confident motto, from the Earl of Dalhousie, was adopted, “Ora et labora.” There seems to be a modern impression, owing to the great diminution of Latin literacy, that these are pious nouns. Quite the contrary; they are verbs, and stern Presbyterian imperatives at that: “Pray and work.” Five of the six professors first appointed were Presbyterians, used to both. Six professors had been appointed by this time, of whom five had arrived. The two nominated by the United Presbyterians were James Ross, professor of ethics and political economy, and principal, and Thomas McCulloch, Jr., professor of natural philosophy, both formerly at Truro. The Kirk nominee was Charles Macdonald of Aberdeen, whom George Grant knew and respected, professor of mathematics. For the three appointments available to them, the Dalhousie governors had the happy idea of appointing William Lyall, also of Truro, as professor of metaphysics, regarded by many as pre-eminent in British North America.

All of that was decided by early August 1863. Advertisements were placed in the Toronto, Saint John, and Charlottetown papers for applications to the chairs of classics and chemistry, and for a tutor in modern languages. There were eleven applicants for the chair of chemistry, including Abraham Gesner, the inventor of kerosene. The governors chose George Lawson of Queen’s University, Kingston, whose specialty was botany as well as chemistry. All five appointees so far were Presbyterians. The sixth chair was classics. Dalhousie would have liked to appoint the Reverend Dr. John Pryor, former president of Acadia, and now minister of the Granville Street Baptist Church. But he would not accept the basic condition of giving up his pastoral charge, so John Johnson, MA, an Anglican and Irish, was appointed.[9]

The one person who was not there was Charles Macdonald, whom the governors had not notified directly, assuming that his friend and Dalhousie governor, George Grant, would have done that. The board only found out at the end of October that Macdonald was awaiting formal notification. The day he received it, he resigned his Aberdeen charge; he would sail for Halifax in December, and would be ready for duty on 4 January.[10]

Dalhousie and Its Staff

The old Dalhousie building seemed positively palatial to the forty students who came that first session. Viewed from the north it was a big building, four stories high at the Duke Street level, even though at the Parade level it was only two. At the lowest level, with entrance only on Duke Street, were the vaults of Oland’s Brewery. Students were jocular about the brewery. Parents in the country, said the Dalhousie Gazette, who worried about sending their sons to Dalhousie and their not being able to get enough beer, could rest easy.

“The Brewery,” reasoned the Governors of the College, “will be a great help to our College, as it can afford to pay a good rent.” “The College,” reasoned the Governors of the Brewery, “will be a great help to our Brewery, as the students can afford to pay well for good beer.” Thus they are mutually dependent on each other.

There was also a shop facing Barrington Street. On the second level, still below the Parade, were student rooms, accessible from above, a reading room, and a lounge where, as one student remembered, “all the mischief going was planned.”[11] The janitor and his family occupied the other rooms on that floor. Errol Boyd had been in his position since February 1824; forty-four years of rent-free accommodations may have given him and his family a sense of owning the place. From the smells working their way to the floors above, it seemed to the professors that Errol Boyd was running either a cooking school or a boarding house; the smells of cooking, in the mornings especially, were so strong, professors were “so overpowered with the odoriferous energy as to be on the point of… dismissing their classes.” Who could concentrate on quadratic equations if one’s mid-morning hunger were tempted by the luscious smell of roast beef, or even corned beef and cabbage? Boyd was told about it, but couldn’t or wouldn’t change. A new janitor was engaged, a quaint and likeable character named John Wilson.

On the Parade level, the college’s main entrance and the two entrances on either side bridged a deep moat that gave light to the basement story where the postmaster and his family lived. Dalhousie’s main entrance gave onto a large T-shaped hall eight feet wide that went the full thirty feet to the back of the building, past a large semi-circular staircase; at the back it branched twenty feet each way, east and west, into two large wing rooms. There were smaller rooms off the main corridor. The building was heated with beehive stoves[12], in each room, which were fed from a vast four-foot-high coal box placed into the window recess at the junction of the T. The hall was the main student meeting place, where songs and what were called “scrimmages” took place. A scrimmage is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “a noisy contention or tussle.” Both songs and scrimmages were not infrequent, but seem to have been confined to times when lectures were not being given. Professors did not positively prohibit them but there were attempts to restrain their excesses. Charles Macdonald used to say, “There is nobody more tolerant of fun than myself when it reveals the presence of genius, and nobody less so when it is guided by stupidity.” Where scrimmaging lay between those polarities was not always easy to discern. One student exercise was to see that every freshman was elevated onto the coal box, where they had to make a speech. One strong, six-foot freshman bragged that he would like to see sophomores try to elevate him. It was being duly done by a group of them, when who should walk by but Professor John Johnson. Just as D.C. Fraser was depositing his end of the load on the coal box Johnson, his Irish eyes sparkling with merriment not severity, said, “A little less energy, Mr. Fraser; much less energy.”[13]

On the second floor were two rooms, the west one initially being the chemistry room, and the east occupied by Principal Ross who lectured on ethics and political economy three days a week. Under the roof, and giving access to it, was an attic, reached by a ladder. Eventually it would be converted into a chemistry laboratory. In winter excellent fun was to be had getting out onto the roof and pelting the passers-by below with snowballs. The pupils of the National School across the way, described by James Ross as the “rising savages of Halifax,” were a tempting target.[14]

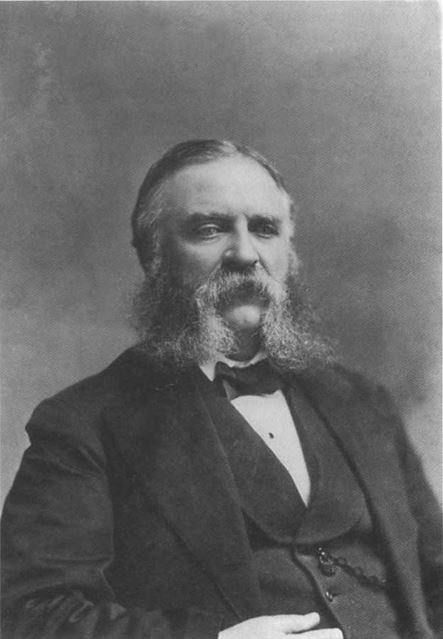

James Ross, the first principal of Dalhousie, was born at West River in 1811 and educated at Pictou Academy under McCulloch. His school mates had been J.W. Dawson, William McCulloch, and J.D. MacGregor. He was himself the product of a minister’s home, one of fifteen children. He was about to go to Edinburgh University when he was urged to replace his father, who had died in 1834, at the West River Church. Duty triumphed, and eventually the West River Seminary evolved. Ross taught everything – Latin, Greek, mathematics, logic, moral philosophy, and in alternate years, physics and chemistry. He was named by the United Presbyterians as their appointee to the professorship of ethics and political economy at Dalhousie, and was made principal by the Dalhousie board, partly owing to his role at the college at Truro of which he had been principal.

He was now fifty-two, a useful and varied teacher rather than a scholar. He had stopped formal education when he was twenty-two, but he had learned much from McCulloch that stood him in good stead, and they remained in touch. There was no hypocrisy in McCulloch’s comments to Ross when he was a young man. Your father was good, he said, but lacked fire. It is probably constitutional in your family, and for that reason “I have the more frequently impressed upon yourself the importance of energy.”[15] There is evidence from Dalhousie students that James Ross never quite overcame this torpidity. His beautifully neat lecture notes came from a neat mind, but were delivered with a marked absence of vigour. As if to compensate for the absence of fire in his classes, he was a generous marker of examinations.

Ross took nothing for granted. If he took on a subject, he started at the foundations, deploring easy generalities. The students complained that he too often treated them like schoolboys. In some ways that was true, but it had virtues. G.G. Patterson said that while he had written many essays in Latin, and some in Greek, he had written none in English until one in metaphysics for Lyall in his third year (which was not returned) and two for “Jimmie” Ross in the fourth (which were returned, and closely marked). Like McCulloch, Ross hated superfluity.

There was also a certain taciturnity in Ross. Benjamin Russell, later jurist and teacher at Dalhousie Law School, went to Ross’s very unpretentious house on Maitland Street in August 1864 to inquire about admission to Dalhousie. Perhaps even then one did not go to the principal’s house with such questions, or Ross was wakened from a nap, for when he crossly came to the door without collar, he grumbled to Russell that most matriculation students did not know their Latin conjugations well enough. Russell, who did know, found him so disagreeable that he decided to go to Mount Allison instead. Certainly Ross had no great place in students’ affections. He seems to have been conscious of two things especially: how much the success of the college depended upon him, and how short of money Dalhousie really was. Dalhousie lived on the edge of financial disaster for two-thirds of his presidency. Ross may well have been one of those unremembered presidents who are better at preventing evil than creating good.[16]

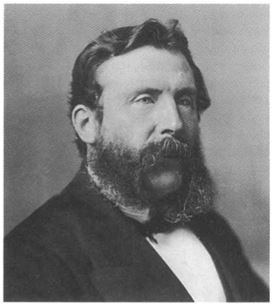

Charles Macdonald, professor of mathematics from 1863 to 1901 had taught for some years in high schools in Edinburgh and Aberdeen before coming to Dalhousie at the age of thirty-five. He was a gifted teacher. Not only did he have a wide and trenchant knowledge of his subject but singular brilliance in its exposition. He was accurate and precise, but far from being coldly logical or pedantic. He loved his work, and it showed. He positively revelled in what he was doing. “Gentlemen,” he would say in effect, “I am ravished with the thought of introducing you into the delightful mysteries of mathematics, in which recreation I am confident we shall both enjoy ourselves.” That invitation students found irresistible. “Lead on,” they would say, “we long to follow such a charismatic leader.” There would he stand, his coat covered with chalk dust (for he did not wear a gown), his massive, leonine head thrown slightly back, his face radiant with the idea of opening up to those young minds a new field of knowledge, wholly certain he would carry most of them with him. He did not overburden his courses, but preferred discussion across a fairly narrow range. Thoroughness was what he was after. He had his touches of theatre. After a particularly good class he liked to throw the chalk backwards over his head and hit, more often than not, the waste basket in the corner. The students loved that stunt, and would cheer and clap with delight.[17]

Charlie, as the students called him behind his back, could say harsh things, more so than his colleagues, but he would say them with such humour and raciness, and with such a genial smile, that his remark would have the edge taken off it. When some student was flying too high, assuming too much, Macdonald would interrupt with a few coughs and say, “Euclid thought differently but he must have been mistaken.” A student was grinning at something private one day, and Macdonald, who did not like such disruptions in his class, asked the student what he was grinning at. To get laugh from his fellows, the student said, “My own folly!” Macdonald could always go one better. “You’ll find it,” said he in a flash, “an inexhaustible source of amusement.” All this with his Aberdeen accent. A student was giving some exposition of Euclid. “Your arguments,” said Macdonald, “lack cogency, it’s a spley method of speech ye have. It’s not gude… Use the first equation as a sort of sledgehammer to break up the others.” He did not like his mathematics closed in by too vulgar an emphasis upon the practical applications of it. Asked by a student if he were going to teach “practical mathematics” (by which the student meant things like navigation, or surveying), he replied, “Practical Mathematics! You are here, Sir, to learn a modicum of Mathematics.”

New students were apt to fear him. Dalhousie entrance examinations in mathematics were partly oral, which had the virtue of allowing Macdonald to become acquainted with his students. One entering student was not very big and was much in awe of Professor Macdonald at close quarters. Macdonald asked him a question about parallel lines, and then, hearing the student was from the Eastern Shore, went on to talk about fishing in the Salmon River. A pat on the shoulders, and the dread ordeal was over.

Life would be intolerable, Macdonald used to conclude, but for its fun. He had no great confidence in the immediate victory of merit, wisdom, justice. In the short run, he would say, humbug, pretence, and brazen self-assertion can often prevail against wisdom and “wide-horizoned thought.” In the long run, the latter win out, but it is a very long run. He had his touches of whimsy. An invitation to tea to a lady student in the 1880s:

Carissima Puellala

March 2

Will do

At 6 p.m. for Miss B. and you

C.M.

Of medium height, with a strong, well-knit frame, he liked to begin his Saturdays with a walk around Bedford Basin, a good fifteen miles. He was a great fisherman, and worked every good stream in convenient reach of Halifax. When James De Mille came in 1865, the two became boon companions, talking of their favourite subject – trout and salmon – in Latin. The most popular professor on staff, Macdonald carried the whole formidable mathematics curriculum on his broad shoulders from 1863 to 1901.

The other pillar of the Dalhousie curriculum was, of course, classics. John Johnson was twenty-eight years old, an MA from Trinity College, Dublin, as Irish as Charlie was Scottish. He had wit and charm, but he was less forthright; his shafts were more delicate, the way he was, crafted more gently. He was professor of classics from 1863 to 1894. His manner was at once cool and precise. One student remembered him skating by himself up at the far end of Second Lake in Dartmouth, where he fell heavily and broke his leg just above the ankle. He had to be got to the foot of First Lake somehow. A rude conveyance was made from a young spruce tree and thus he was dragged the three miles over the ice. Not a groan escaped him; he seemed more cheerful than anyone.

Johnson’s classes could never be taken for granted, nor his examinations, for he was a close marker. You could not work off some glittering generality on him. If your answers were not to the point you might just as well forget it.[18]

His classes were terrors to those reluctant to work. One student, trying to pass a Greek examination, used a translation, regarded then, and one hopes now, as counsel of desperation. It worked, and he received a better mark than many in class who were better Greek scholars. At the beginning of next term, asked questions in Greek class, the student gave such idiotic answers that Johnson, tightening his gown around his shoulders as he did when he was angry, said, “Dear me, Mr. X, how did you pass your last examination?” Then realizing what had happened, he added, “My lad, I will look after you at the next.” No professor likes being hoodwinked.

Being Irish, Johnson was fond of rugby and followed the fortunes of the Dalhousie team rain or shine. Few were as faithful as he to the fortunes, good or bad, of Dalhousie rugby.

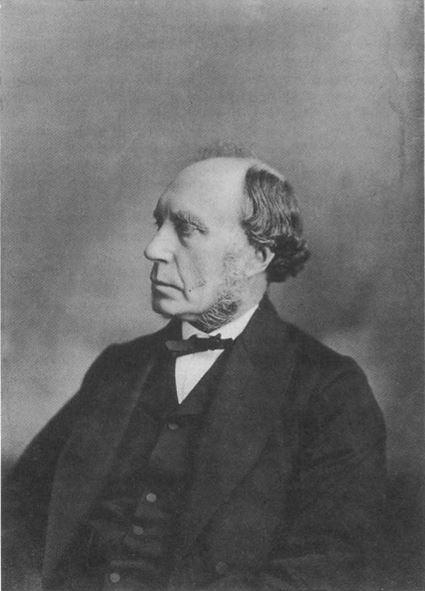

The oldest member of staff was William Lyall, professor of logic and metaphysics from 1863 to 1890. Lyall was born in 1811, educated at Glasgow and Edinburgh, and had been a tutor at Knox College at the University of Toronto. He then went to the Free Church Academy at Halifax, and so to Dalhousie via Truro. McGill gave him an LL.D. in 1864, and he was elected a charter member of the Royal Society of Canada when it was started in 1882. Lyall’s philosophy derived mainly from the Scottish common-sense school and, like Thomas McCulloch, he was much influenced by Thomas Reid and Dugald Stewart. His first book, Intellect, the Emotions, and the Moral Nature, was published in 1855 and is one of the first written in Canada in the field. In that book philosophy was set down as the handmaiden of religion. “Philosophy may speculate: the Bible reveals…” was the way Lyall put it. He was unusually self-effacing, having what one student called “the transparent innocence of a pure mind.” He often forgot to check his watch. On one occasion, noting the class was running late, the students silently agreed between themselves to let him keep going, to see how long he would go on. After a further hour, one of the hungrier of the class could stand it no longer and began to shuffle his feet. Much embarrassed and disconcerted, Lyall stopped. But the students gave him a fine round of applause just the same. Sensitive, shy, quiet, Lyall was one of the truest scholars of the Dalhousie sextet, and one who much enjoyed his teaching. He was, in his range of interests, as someone remarked, “a whole faculty of arts.”[19]

George Lawson, professor of chemistry from 1863 to 1895, came from Fifeshire and graduated from Edinburgh. He lectured at one time in science at Edinburgh, took his PH.D. at Giessen, the only Dalhousie professor of 1863 to have one of those new-fangled German degrees. Lawson was widely published and, like Lyall, was among the original members of the Royal Society of Canada, of which he became president in 1887. His real work was in botany, but he had great interest in agriculture, and was for twenty years secretary of the Nova Scotia Central Board of Agriculture. Lawson was big, bluff, rather easy-going in class. If you did not pay attention to what he was saying and doing, that was your problem, not his. He gave the inaugural address at the fall convocation of 1877 and touched on this theme. A professor’s duty was to teach willing students, to set the subject before them in ways that would enable them to grasp it with the exercise of their own wits. The unwilling, or the careless, fell behind. Such students were apt to develop what every professor disliked in class, “bodily activity combined with mental indolence.” That he hated.

Lawson had the power of rousing the enthusiasm of his students, teaching them to use their own powers of observation. He was a good man in the field, and he conducted his own field research classes in the summer, at his farm at Sackville and elsewhere. His major contributions to botanical research were on the Canadian east coast and the Arctic. His influence was such that by 1890 most if not all the leading botanists in Canada had been trained by him.[20]

The sixth professor was Thomas McCulloch, Jr., professor of natural philosophy. He was the third son of Thomas McCulloch but was not quite a chip off the old block. After being principal of Dalhousie briefly in 1849, he was appointed to the West River Seminary under James Ross. He duly moved to Truro in 1856, where he taught natural philosophy and mathematics. He had never been physically strong, and he died in March of 1865, at the age of fifty-four.[21]

After the death of McCulloch, a committee of the Board of Governors was struck to see what best to do. An ingenious change was worked out with the United Presbyterians, whose professor McCulloch had been. Their Synod now resolved, through the Rev. Peter MacGregor, that as exchange for Dalhousie’s courtesy in originally appointing Lyall on Dalhousie money, they would take Lyall now upon their charge, thus freeing a chair. The Dalhousie board then turned in an unexpected direction. Perhaps in their canvass of Dalhousie offerings, they reasoned that Lawson could carry some physics, that Macdonald could handle some mathematical physics, that Lyall might manage some psychology, and hence the professorship of natural philosophy (physics) could wait for a time. The board advertised simply a position, while they were working out what best to do. An early applicant was James De Mille, professor of classics at Acadia College. He had many other talents, and on 11 September 1865 he was appointed to the new chair, called rhetoric and history.[22]

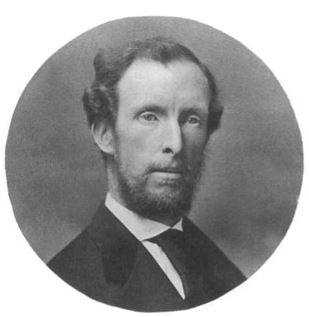

James De Mille came from Saint John, New Brunswick, from a family of Dutch origin that had migrated to New York in 1658. A branch came to Saint John with the Loyalists in 1783, where James was born fifty years later. The family were Baptists, sober and diligent, and were sufficiently well off to see that James went to a good Baptist school, in this case, Horton Academy in Wolfville. De Mille attended Acadia for a season, then took a six-month tour of Europe, most of it, sensibly enough, in Italy. He then went to Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, graduating in 1854. After a stint as a bookseller in Saint John, he was appointed to Acadia as professor of classics in 1860. He did well there. Why he resigned in 1865 to come to Dalhousie is not clear. The Dalhousie pay was certainly a little better; or De Mille may have preferred teaching history and rhetoric to classics, or Halifax to Wolfville. The Dalhousie board went to some trouble with his appointment, for it required a rearrangement of the whole curriculum to enable them to appoint him.

He was liked from the start. He was dignified, handsome, from which not even a heavy pair of glasses detracted. He was a little aloof perhaps, which was compounded by his short-sightedness. He did not always recognize his students; Patterson remembers how he was passed by unnoticed on the Grand Parade, but immediately after De Mille, prompted by his son, turned and greeted Patterson with great warmth. De Mille was something of an outdoor man, loving to swim in the North West Arm and skate on the Dartmouth Lakes. He was a great fisherman; trout and salmon streams allowed him, with his son, or with Charles Macdonald, to combine two happy avocations. De Mille was a charming talker, especially in small company, for he had a wealth of historical and literary allusions at his fingertips, and a singular facility at imparting them.

His lectures did not always claim his full attention. There was occasionally a mechanistic, perfunctory element in them that led one student, Edwin Crowell, to think that De Mille’s real interests were elsewhere. Nevertheless, most students liked his infectious and sprightly performances, and if a lecture were to be skipped (“slope” was the verb used in the 1870s), it was not apt to be Professor De Mille’s. He had a richly modulated voice, a capacious grasp of English; his history was never static, but dialectical; it was, as one student remembered, “a moving, living panorama.” In 1878 he offered a special fourth-year course in the history of Canada. This was probably the first time such a course was offered in English Canada. For most students De Mille’s lectures always ended too soon. All students studying for the BA had to take his first-year class in rhetoric; many general students registered for his class alone, not least among whom were W.S. Fielding (who became premier in 1884) and Charles Hibbert Tupper, the vigorous son of a redoubtable father. Students were proud of De Mille, proud of his fame, and many treasured him as a friend.[23]

At the same time as De Mille was appointed, James Liechti was hired as tutor in modern languages. Liechti was Swiss, a Lutheran, who had taught French and German in the Halifax Grammar School for six years. He was liked by students, patient, kind, hardworking. In 1883 he became McLeod professor of modern languages. He survived longer than any of the original old guard; he retired in 1906 to Lunenburg and lived until 1925.

Curriculum of the 1860s and 1870s

The Dalhousie curriculum of the 1860s and 1870s was conventional enough for the time, laying great stress on mathematics and classics; but it was developed and laid out with Scottish rigour. First of all, matriculation examinations were required for entrance, all of them three hours long, and formidable enough. The French entrance examination, for example, gave a quotation from Voltaire’s Charles XII for translation into English: “Le czar, qui dans de pareilles saisons faisait quelques fois quatre cents lieues en poste, à cheval, pour aller visiter lui-meme une mine ou quelque canal, n’épargnait plus ses troupes que lui-meme.” Those were just three out of twenty-five lines for translation, plus detailed questions of selected points of grammar. The German paper was similar. In classics, translations were required from “one easy Latin” and “one easy Greek” author. These were usually Caesar, Virgil, Cicero, or Horace; Xenophon, Homer, Lucian, or the New Testament. The mathematics exam comprehended arithmetic and Book I of Euclid. A further examination included English grammar and composition, the history of England, and geography. Students took examinations in October, two or three days prior to the opening of lectures.[24]

Once past that hurdle, the student settled into his first year. By the 1870s this was classics and mathematics, plus rhetoric, all three of them daily. This regimen continued in the second year, with chemistry, logic, and psychology added. In the third year classics and mathematics were continued, plus experimental physics, mathematical physics, metaphysics, French or German, Greek or chemistry. The fourth year gave Latin, ethics and political economy, history, French or German, astronomy and experimental physics. That meant four courses in the first year, five in the second, six in the third, and five in the fourth. Failing more than two classes in any year meant the year had to be repeated. In 1866 the Senate brought in a rule that classics and mathematics were each reckoned as two subjects! Students were allowed a supplemental examination in the autumn. One historian of Nova Scotia, David Allison, thought the Dalhousie regimen positively draconian, but he was not a Dalhousie man. Dalhousians were proud of it, and believed it the basis of Dalhousie’s reputation. Johnson and Macdonald, the classicist and the mathematician, had between them established that powerful, and exigent, tradition. And though in later years more flexibility was added to the curriculum, that core of classics and mathematics would remain, if in a gradually more attentuated form, until the 1960s.[25]

Dalhousie examinations were printed and published as an appendix to the calendar. These examination papers offered a guarantee, as nearly as could be managed, of a university’s standing. There you displayed what you had to do for the degree. Of course, the next question was, how were the examinations marked? Dalhousie offered no figures itself, but the students did, and they were proud of them. One of the medical professors had charged that all the arts colleges in Nova Scotia were lax in examination standards. The Dalhousie Gazette corrected him:

Now if the [medical] gentleman had excepted our college by name his statement would have been perfectly correct; for it is a notorious fact, admitted by themselves that plucking is almost unknown in the other colleges of Nova Scotia. But it is altogether vain for any man to decry the strictness of our examinations in the face of the evidence afforded by their results. More than once twenty per cent, of our undergraduates have failed to pass, a proportion not exceeded in any college on the continent. Why, last year our examiners plucked nearly as many men as attended King’s College. Least of all ought the charge to have come from any member of the Medical Faculty whose students, though we have personal knowledge that they study not a whit harder than we do, make from 80 to 95 per cent, on their examinations.[26]

As the students put it in the Gazette, 11 January 1873,

Dalhousie claims for herself no indulgence and wants no man to believe in her professions without sufficient proof. What she promises to teach she does teach thoroughly and this her examination papers prove beyond all dispute. They are open to public inspection, and every man in giving his son as a foster child to Dalhousie knows exactly how that son is to be trained, because he has proof positive.

Dalhousie Students of the 1860s and 1870s

Dalhousie students were usually recognizable. The Senate required that all students wear mortar-boards and gowns, not only while at Dalhousie but going to and from as well. A common sight around the Parade was a “black angel,” mortar-board on head, hurrying to class, his gown blowing in the wind. Mortar-boards were more honoured in the breach than the observance, however, and outside the college grounds gowns tended to become scarcer after the first term. They were the target for every ragamuffin who had any latent combative instincts. Duncan Fraser (’72) and a friend were walking to Dalhousie one cold winter morning and were accosted by a gang of city boys, who taunted them about their garb. To Fraser’s surprise, his companion hit out right and left and of course Fraser had to join in. In the end, as Fraser put it, “the oatmeal in our systems prevailed.” Gowns acquired their own patina of age and experience; the more tattered and battered the better.[27]

Dalhousie students did have minor wars with the locals. The Dalhousie Gazette found that crossing the Parade one risked getting mixed up in their games and the target of ordinary balls, snowballs, or even rocks. It was not always war. The Gazette felt sorry for some of the little fellows; imps they were, but it was not their fault: “Your mother suckled you on gin, and your father patted you with the leg of the chair, you were turned out on the streets when you could toddle.” What pious Halifax did for such scamps, said the Gazette, was to send them to prison at Rockhead, through the unsympathetic ministrations of Judge Pryor.[28]

Students usually entered Dalhousie at the age of twenty or twenty-one in the early days. The reason was partly the scattered and feeble character of the secondary schools, with no uniform curriculum. Halifax itself did not have a public high school until 1879. Duncan Fraser of New Glasgow came to Dalhousie when he was twenty-three. Many students had been part-time or full-time teachers before coming to Dalhousie. R.B. Bennett (’93) was a characteristic example, arriving at Dalhousie at the age of twenty after having taught school since he was seventeen.

Students tended to lodge together. Each would take turns cooking; one would buy the food, the coal, the candles or kerosene for a week, the next week another would take over. The diet was oatmeal porridge, saltfish, corned beef, lots of bread. Two enterprising Pictou County students, who came to Dalhousie in 1868 and roomed together north of the Citadel, brought with them three barrels that stood in the hall outside their room – one each of oatmeal, apples, and potatoes. Entertainment was the Debating Society on Friday nights, and Saturday afternoon rugby. Every student took part in the debating society. High-flown oratory was discouraged, and classical allusions considered pedantic. As to rugby, no one prior to about 1867 had ever seen a game. A book of rules was bought, a portion of the North Common pre-empted, and the Saturday afternoon rugby was started, usually going on until snow and ice compelled capitulation.[29]

There were few Halifax-Dartmouth students in the twenty-seven regular undergraduates in 1865-6; twelve came from New Glasgow, Pictou town or Pictou County, two from Halifax-Dartmouth, three from the Annapolis Valley, and three from Prince Edward Island. In 1871-1, of forty-eight undergraduates, twenty-seven came from Pictou County, nine from Halifax-Dartmouth. That year there were twenty-five general students as well, of whom ten were from Halifax-Dartmouth.

Dalhousie also had a diversity of religions. It did not call itself a Presbyterian college, though its detractors did. The Dalhousie Gazette pointed out in 1875 that the Board of Governors, Senate, and student body all had representatives from every denomination in Nova Scotia. Although a majority of students were, indeed, Presbyterian, there seems to have been little animosity between different religious denominations. The four editors of the Gazette were elected annually by the student body; the Gazette was proud to boast that in 1874-5 two were Wesleyan Methodists, and that in 1873-4 one editor was a Roman Catholic.

The Faculty of Medicine

The Faculty of Medicine was opened for the first time in early May 1868, its first session running to the end of July. It had been talked of as early as 1843, but held up by lack of clinical facilities. By 1859 there was a hospital; after a decade of attempts, Halifax City Council in 1855 voted £5,000 for it. It was completed in 1859, on a site between Morris and South streets, west of Tower Road, where the Victoria General Hospital now stands. Local doctors welcomed it, not only to help the poor – its main patrons then – but as a place where clinical work could be carried on.[30] As early as November 1863 the secretary of the Dalhousie board wondered if the Nova Scotia Medical Society was interested in discussing a possible Faculty of Medicine. One great difficulty was the lack of local expertise to teach clinical subjects. Another was the absence of any law authorizing dissection. An Anatomy Act was mooted in 1858 but public opposition was too strong. “An Act Respecting the Study of Anatomy” was passed in 1869, despite strong opposition from outside Halifax. It gave the doctors the right to dissect men who died in the poorhouse at the corner of South and Robie streets. Even after the Anatomy Act, there was a shortage of bodies. A young hospital attendant told police in 1874 that the body of a young man, Michael Gleason, who died in February, had been delivered to the Dalhousie Medical Faculty; that the coffin, over which a funeral was held, had nothing in it but rubbish. It was true; the coffin was found to be full of old hospital bedding. Cordwood was another favourite replacement. Such stories tended to confirm public suspicion of hospitals, medical schools, and dissection. Nevertheless, there was a real public need.[31]

The moving spirit in the creation of the Dalhousie Medical Faculty was Dr. A.P. Reid, a man of considerable experience and distinction, and also eccentricities. Born in London, Upper Canada, in 1836, he graduated from McGill in 1858, doing postgraduate work in Edinburgh, London, and Paris. He had many adventures, not least going to the west coast of British North America, before ending up in Halifax as dean of medicine. In August 1870, after a trial of two years, it was agreed that a full medical school should start as of 1 November. The original plan was that students would do two years in Halifax and then go off to Edinburgh, London, Harvard, or Pennsylvania to complete their medical training. Some did, but five of the original twelve stayed at Dalhousie and were thus its first medical graduates. Medical degrees would carry the seal of Dalhousie College and the signatures of Sir William Young, chairman of the Dalhousie Board of Governors, Principal Ross, and Dr. W.J. Almon, president of the faculty. The Medical Faculty functioned virtually as an autonomous unit; the relations between it and Dalhousie were as loose as possible consistent with any affiliation at all. In effect, Dalhousie granted the space and the use of its name for the degrees.[32]

There was difficulty with space. The board finally got the provincial government to remove the museum from the East Room so that the medical students could have a lecture room. The Dalhousie attic was converted into a dissecting room, with the light bad and the ventilation worse. In summer it was a good place to avoid; an old cadaver and a month of heat under the roof produced disconcerting results. The faculty was also a drain on funds for chemicals and apparatus, now deemed indispensable.

Medical school ambitions were difficult to contain. Dalhousie principals and presidents were not the first, nor the last, to find their medical deans were more to be feared than loved. They needed more money for their work and they needed more space. Space could have been arranged in another building by means of a trust, or by an act of incorporation for that single purpose. What emerged in 1873 was an act creating the Halifax School of Medicine that gave powers to its governors to appoint professors and make by-laws. “As the law stands the [Dalhousie] Governors cannot see how it is possible for them to affiliate with any independent institution so as to legalize their degrees.” So they said in May of 1873. The Medical Faculty replied that they did not wish to separate from Dalhousie, and had not thought the 1873 act would have that effect. But Sir William Young was also chief justice of Nova Scotia, and his view was that under the 1863 act Dalhousie could not confer degrees on students of the Halifax School of Medicine, and that if the faculty were organized under the 1873 act, separation from Dalhousie would follow. The Halifax Medical School sought to avoid the full ramifications of this, not wanting to give up that Dalhousie imprimatur. But they still needed a new building, and wanted Dalhousie to help bear the expense. At that the Dalhousie board virtually threw up their hands: “Your Colleagues must be aware that the [Dalhousie] Board cannot possibly accede to these proposals. From the beginning they have never once been left in doubt as to what the Board could do and what it could not do.” Those who were dissatisfied with the existing and well-defined relationship with Dalhousie should resign from it. That was a reference to divisions of opinion within medical ranks, about what best to do.

In 1875 the Dalhousie board agreed to allow medical students to have their own convocation, with Dalhousie degrees; but that year, a further Act of Incorporation created the Halifax Medical College giving additional powers, including that of conferring degrees. Separation was now inevitable. In the Dalhousie calendar for 1876-7 all reference to the Medical Faculty was omitted; Halifax Medical College granted its own degrees until 1885.[33]

The Colleges Question Revived

Joseph Howe, who had been on the Dalhousie Board of Governors since 1848 and had given yeoman service, died on 1 June 1873. His successor on the board was the Reverend George W. Hill, rector of St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Halifax, the brother of P.C. Hill who would become premier in May 1875. At his first board meeting on 23 January 1874, Hill raised the question of a more ample provincial grant, and furthermore, of the necessity of getting the other colleges to think seriously about the advantages and possibilities of a central university for Nova Scotia. The previous May the board had sent a circular letter to Acadia, King’s, St. Mary’s, St. Francis Xavier, and Mount Allison, suggesting that their several boards nominate delegates to meet and discuss the question. Dalhousie got short shrift for its pains; the idea was turned down.

That having failed, the Dalhousie board next struck a committee to prepare a submission to the legislature for more money. It was a good state paper, presenting a short history of the college, its present position, and its needs. The gist of the argument was financial. The other five colleges each received $1,400 from the legislature; all Dalhousie got was $1,000, inherited from the old Assembly grant to the Free Church College. Had the Presbyterians not combined to help resuscitate Dalhousie, chances were that they might have been given $1,400 each for two colleges, the way the Roman Catholics had with St. Mary’s and St. Francis Xavier. It looked to Dalhousie as if “no matter how many small colleges you choose to establish, we shall give $1,400 a year to each; but attempt to combine your resources and we shall give you nothing.” Should not Nova Scotia now take up a policy similar to that in Ontario (the University of Toronto), or New Brunswick (the University of New Brunswick)? Was it not obvious that no denominational college in Nova Scotia was strong enough “to fully equip a university”? Surely, said the Dalhousie petition, “the time has come for the Legislature to take its stand on one principle or the other: on the Denominational or the Provincial … At present Dalhousie suffers injustice because neither the one nor the other is allowed.” The salaries to its professors, first set in 1863, were now inadequate. Enrolment at the college was growing; in the session of 1874-5 Dalhousie had eighty-seven students in arts, thirty-three in medicine – larger than all the other Nova Scotian colleges combined.[34]

The government recognized the validity of Dalhousie’s argument and increased the grant to $1,800 for 1875-6. But the following year a new act was brought in, establishing, though in an odd way, what Dalhousie looked forward to – a central university for Nova Scotia. This was the University of Halifax.

The college question was a little like measles or whooping cough, breaking out every now and then in the body politic of Nova Scotia. The University of Halifax was a pet project of the premier’s. P.C. Hill was a graduate of King’s, urbane, civilized, but politically naive. His act of 1876 was courageous. Its preamble stated:

Whereas it is desirable to establish one University for the whole of Nova Scotia, on the model of the University of London, for the purpose of raising the standard of higher education in the Province, and of enabling all denominations and classes, including those persons whose circumstances preclude them from following a regular course of study in any of the existing Colleges or Universities to obtain academical degrees.

There was real idealism in the proposal, in effect setting up a central examining body with the existing colleges doing the teaching. The trouble was, the Hill government had courage but not enough strength to effect what was really needed: to draw the teeth of the six colleges by abolishing their degree-granting powers. Probably the government knew it could not do that and live. On 10 March 1876 it came close to losing the bill altogether, surviving a Conservative motive for the three months’ hoist by only three votes. According to the Halifax Evening Reporter, the whole measure was a compromise to give those who wanted a non-sectarian institution five years’ time to “to work up an agitation in favour of one central teaching university.” It can also be said, as the Pictou Standard did, that the creation of the University of Halifax was an admission that the government would not do what it also might have done – give its $8,000 university grants to Dalhousie, the one college that was central, that professed to be, and was in principle, non-denominational. That course, said the Standard, “Catholics, Baptists, Episcopalians and Methodists would have resisted … to the last extremity. ” That was what Samuel Creelman, commissioner of public works and mines, said in the Legislative Council in 1881. The reason why the University of Halifax had to be created, instead of using Dalhousie, was because the other colleges would not have it. They would not send any students to Dalhousie.[35]

Dalhousie’s position had long been that university education in Nova Scotia was too important to be left to the vagaries of “Church, Chance or Charity.” This did not endear it to those colleges so created. According to the Gazette, Dalhousie was “a kind of modern Ishmael, – hating and being hated by the other five colleges.” In Professor Lyall’s address to convocation, in 1874, he had pointed out, “We have existed under a kind of protest. A portion of the community has frowned upon us; rival institutions have been jealous of us.” One correspondent in the Halifax Evening Reporter deplored Dalhousie-bashing, and claimed it originated mainly in Wolfville. Surely, said “One of the People,” the Crawley affair could have been forgotten by now? Dalhousie, the “People’s College,” had done much in the last ten years to atone for past sins, “by the numbers taught, by the acknowledged excellence of its teaching, by the liberality of its government.”[36]

The Dalhousie Gazette‘s criticism of the University of Halifax was based on the false premise under which it was started. England at the time the University of London was established had excellent teaching facilities but, outside of Oxford and Cambridge, no power of conferring degrees; “in Nova Scotia we have most admirable arrangements for conferring degrees but wretched facilities for imparting a good education.” “The new Paper University will be almost helpless” to remedy that. It might give unity to study; it may expose shams “lurking in the examination-paper-less obscurity” of some colleges; but it can do little to strengthen the universities where they need it: in teaching.[37]

Dalhousie mounted a longer and more serious criticism in 1877 (anonymously but probably by Charles Macdonald), in a twenty-two- page pamphlet. It likened the sectarian colleges to “sturdy beggars hustling with shout and menace a simple-minded gentleman from whose fears more is to be expected than from his pity.” The simple-minded gentleman, the Nova Scotian government, had been handing over money, being “incapable of a manful No.” One university for the province was, indeed, highly desirable; to achieve that, degreegranting powers had to be withdrawn from the others. But,

when it is known that the Colleges are to continue to grant Degrees as before, with all the laxity and indiscriminateness with which they are, justly or unjustly charged, we may ask, what evil does the University of Halifax cure? What is it more than an additional Graduating nuisance ? It is the old story, the fifth wheel to the carriage, coals to Newcastle, more Christmas-pie to the already surfeited Jack Horner, or whatever else is superfluous and absurd.

The author condemned outright, as did Dr. Cramp of Acadia, the strange provision in section 15 of the act: that the University of Halifax’s Senate had no power to recommend or urge that any student should study “any materialistic or sceptical system of Logic or Mental or Moral Philosophy.” The author ran a coach and horses through that provision. All he had to do was to mention Lucretius, Hobbes, Hume, Comte, Darwin, Spencer. He concluded that the net effect of the University of Halifax would be to leave the idea of a provincial university still further off than before.[38]

So, in fact, it proved to be. In 1878 and 1879 the University of Halifax examined some fifty-seven candidates in arts, science, law and medicine. Some 30 per cent failed. In 1880 only twenty applied for its degree. In 1881 the University of Halifax came to an end.

That was the strangest part of the story. Its funding of $2,000 a year was to continue until 31 December 1880, after which its functioning, role, and refunding would be considered. By that time Hill’s government had been defeated and replaced by a Conservative one which had much less sympathy with the University of Halifax. There was a good deal of ferment in the autumn of 1880; both leading political papers, the Morning Herald (Conservative) and the Morning Chronicle (Liberal) published a series of articles on the university question. Dalhousie’s position was further stated by J.G. MacGregor, professor of physics, in ten letters to the Morning Herald, from December 1880 to February 1881. The University of London’s example could not be transferred to Halifax. London had large numbers of well-trained students, well-trained specialists to teach them, and no accessible degreegranting university. In Nova Scotia it was the other way. There was no dearth of colleges but a great shortage of specialists. It was the teaching that was weak, and there was nothing the paper University of Halifax could do about that. It ought not to have been founded and should be abolished.

In the 1881 session the Assembly repealed the University of Halifax Act, putting in its place a grant of $1,400 a year to each of the six existing colleges, on condition that they be inspected regularly by the superintendent of education. This bill passed the Assembly by the overwhelming majority of thirty to one. But it got very different treatment in the Legislative Council. The Anglicans were unhappy: King’s College to be inspected by a government official! The Presbyterians thought Dalhousie was being penalized. Others did not like the double grant to the small Roman Catholic colleges, St. Mary’s and St. Francis Xavier. A few wanted to keep the University of Halifax. A motion for the three months’ hoist caught the government off guard; the government leader, Samuel Creelman, desperately tried to adjourn the debate. That failed by three votes, and the three months’ hoist passed by one vote. The Colleges bill was in ruins. This had two effects: it stopped the college grants, and not just in 1881, but for nearly eighty years, and it kept the University of Halifax alive. It was buried anyway.[39]

In 1871 Dalhousie’s need for money had forced the governors to do their own campaigning. Sir William Young, George Grant, W.J. Stairs, and William Doull agreed to try to raise $1,200 a year for five years. They succeeded. It may also have been the origin of the Dalhousie Alumni Association that began in 1871 and was incorporated in 1876. Even so, Dalhousie lived from hand to mouth. Its total annual income in 1875 was $4,600: $3,000 from investments, $600 rent, and the government grant of $1,000. The arithmetic was fearfully simple. Dalhousie paid the three professors for which it had responsibility $1,200 a year each. They paid Liechti $500, and the janitor got his free apartment and $25 a year. It was very thin going. True, in 1876 Dalhousie got $1,800 from the government, which in 1876 went up to $3,000 for five years. That helped. Dalhousie’s annual income was now $6,600.[40]

That allowed Dalhousie to do what it had been anxious to do for some time: appoint a teacher in physics. James Gordon MacGregor, (BA ’71, MA ’74) was one of Dalhousie’s most brilliant graduates, who had gone on to do graduate work at Edinburgh and Leipzig, taking a D.SC. from the University of London in 1876. He offered himself for a lectureship in physics in 1876. George Grant had urged that a lectureship in physics be established. Unfortunately Dalhousie could spare only $400. Grant volunteered to find another $300, for one year anyway.[41]

The following year MacGregor resigned to take a post as physics master at an English public school, presumably for better pay. The Dalhousie board then appointed Dr. J.J. MacKenzie in 1877. He was another Dalhousie graduate, from Pictou County, (BA ’69, MA ’72), who had taken his PH.D. in Germany. At his urging, the board made a great effort to strengthen Dalhousie’s science. Led by Sir William Young, some $2,500 was collected to enable MacKenzie to buy some physics apparatus in Paris and Berlin in the summer of 1878. A former assistant of Lawson’s, H.A. Bayne, was made professor of organic chemistry, with the Reverend D. Honeyman as lecturer in geology and paleontology. Dalhousie thus began in September 1878 with some hopes that, having strengthened its science curriculum, an increase of students would result.

Sir William Young was concerned to keep the Presbyterian Synod fully informed of Dalhousie developments. He wrote in September 1878 that “no greater misfortune could befall the Presbyterian Body than the failure or degradation of our College.” One current difficulty was Principal Ross’s health. Ross’s strength was much shaken, said Young, and his capacity to teach so doubtful that the question of his retirement on half-pay should be considered by Synod. Synod made non-committal noises to this, but before any decision had been made, MacKenzie died of pneumonia on 2 February 1879, at the age of thirty-one.[42]

The board found the greatest difficulty in replacing him. What they really wanted to do was to retire Ross, and get the Presbyterians to fund a chair of physics, while Dalhousie took on the support of ethics and political economy that Ross taught. Young put it diplomatically in May 1879:

The Governors are sensible that in urging the Synod to accept the Principal’s resignation and in assigning to Physical Instruction [Physics] a prominence it has not hitherto enjoyed, they may be asking some of its members to modify or to surrender cherished opinions but the Governors are pressed by a strong conviction that the course they venture to recommend is of the first moment to the College, and that the delay of even a year, may defeat their object.

But the Dalhousie board now lacked the pulling power of one of the most redoubtable and devoted of its governors, George Grant. He was offered the principalship of Queen’s University at Kingston, Ontario, in October 1877. His congregation of St. Matthew’s were in despair, and his friends tried to persuade him to stay. The new Dalhousie was in no small way the result of Grant’s brimming energy and his enthusiasm for education. After a month of thinking, Grant left Halifax for Queen’s on 26 November 1877. He would be its principal for the next twenty-five years. Grant remained on the Dalhousie board until 1884, giving his advice by mail and on occasional visits to Halifax.[43]

On 9 October 1878 the board appointed in his place an energetic Presbyterian minister, the Reverend John Forrest, of St. John’s Presbyterian Church, Brunswick Street. Forrest was untried, but at thirty-five young and vigorous, and in a decade he had made St. John’s into a large and flourishing congregation.[44] He was the driving force behind much charitable work in the Halifax community. His appointment came at a critical time. Dalhousie was desperately looking for money from a grudging, hesitant, and impecunious Synod to appoint that essential professor of physics. Principal Ross was ill and old, and had never had talent for collecting money. The $3,000 government grant would run out in two years, at the end of 1880. Expenses were pared wherever they could be. Where could Dalhousie go for money? The Presbyterians had done their best, and more; Halifax had not yet taken up Dalhousie as its own college. Then, in the summer of 1879, Forrest had a visit from his sister Catherine and her husband who lived in New York. The husband was very rich, he was Nova Scotian and Presbyterian, and he knew Halifax well. His name was George Munro.

- For the weather report, see Morning Sun (Halifax), 11 Nov. 1863, under “Almanac.” ↵

- For a history of the later stages of the Halifax Citadel, see John Joseph Greenough, The Halifax Citadel, 1825-1860: A Narrative and Structural History (Ottawa 1977), Canadian Historic Sites Series No. 17, pp. 128-9. ↵

- Hugo Reid, Sketches in North America (London 1861), p. 296. ↵

- Morning Sun, 17 Apr. 1863; Morning Chronicle, 18 Apr. 1863; Presbyterian Witness, 18 Apr. 1863. ↵

- The quotation from Burke is from his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790); Presbyterian Witness, 2 Feb. 1856, quoting the Edinburgh Witness; Presbyterian Witness, 9 Aug. 1856; British Colonist, 19 Aug. 1856; Presbyterian Witness, 23 Aug. 1856; Provincial Wesleyan, 9 Sept. 1863. ↵

- Presbyterian Witness, 6 Sept. 1856. ↵

- Morning Sun, 20 Apr. 1863. The Anglican journal is the Halifax Church Record, 2 Sept. 1863. For the chairman’s remarks, see Morning Chronicle, 12 Nov. 1863. De Mille’s remarks are made ten years later, in his inaugural address, see the Dalhousie Gazette, 15 Nov. 1873. ↵

- Morning Sun, 11 Nov. 1863 (italics added). The French quotation means “to move back, the better to jump forward.” The Latin means “I rise again with splendour augmented.” ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 6 Aug., 3 and 19 Oct. 1863, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives; Letter from James Thomson to McCulloch, 10 Aug. 1863, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 24, Dalhousie University Archives; Letter from Thomson to George Lawson, 5 Oct. 1863, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 24, Dalhousie University Archives. Perhaps it was as well that Pryor was not appointed. He got into trouble with his Granville Street congregation in 1867 over misapplication of church funds and impropriety with a woman of doubtful character, and was ousted from his church. A full account of this incident is given in Patricia Monk, The Gilded Beaver: An Introduction to the Life and Work of James De Mille (Toronto 1991), pp. 129-33. See also Barry M. Moody, “John Pryor,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, xii: 871-3. ↵

- Letter from Thomson to Rev. C.M. McDonald, 29 Oct. [1863], Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 24, Dalhousie University Archives; Letter from Charles Macdonald to Secretary of Dalhousie College, 14 Nov. 1863, from Aberdeen, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 24, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- The account here and on the following pages is based largely on descriptive evidence. There is no plan of the old Dalhousie College building that I have seen. In 1871 Dr. J.F. Avery tried to get “the original plan” of Dalhousie College to make some changes after the departure of the post office, but apparently none could be found (Board of Governors Minutes, 25 May 1871, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3). J.G. McGregor, professor of physics, had a sketch of some changes he would like made on the second floor in 1881 (Board of Governors Correspondence, MacGregor to Board of Governors, 3 Jan. 1881, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 14). There are a number of personal descriptions. The earliest is by Calor, Dalhousie Gazette, 19 Jan. 1871. The Gazette issued an important historical number, on 12 Jan. 1903, in which George Patterson has a useful essay on “The Old Building,” pp. 111-19. There is also a photograph, probably taken in the early 1880s. D.C. Fraser reminisces about 1872 in The Gazette, 25 Jan. 1908, pp. 112-18, “M” writes of “Dalhousie in the 60s” in The Gazette, 20 Oct. 1908, as does Dr. J. McG. Baxter in The Gazette, 30 Jan. 1919. ↵

- There is a picture of one, looking exactly like its name, in a photograph of one of the redan residences in the Citadel, taken c. 1890, in Greenough, The Halifax Citadel, p. 103. ↵

- D.C. Fraser, “Reminiscences of 1872,” Dalhousie Gazette, 25 Jan. 1905, p. 117. There is a resolution in the Senate, 2 Feb. 1876: “Students must understand that any act, however trifling in itself, becomes serious when it tends to cause interruptions or distraction in a class, and that it then both necessitates and merits punishment.” Senate let the group of students responsible for an incident off, after their apology, and one third-year student, John S. Murray, was given a warning, that it was hoped he would in future maintain behaviour “unobtrusive as respects his fellow students and, in every instance, respectful as regards his Professors.” ↵

- Allan Dunlop, “James Ross,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, xi: 773. The Board of Governors registered a complaint against the boys of the National School for shouting and throwing of stones, “a most serious evil for some time past.” The board was to ask the school to confine the boys to a line south of George Street, Board of Governors Minutes, 12 Nov. 1875, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from McCulloch to Ross, 16 June 1835, from Pictou, box 22, Thomas McCulloch Papers, Maritime Conference Archives. ↵

- Morning Herald (Halifax), 16 Mar. 1886; E.D. Millar, “Rev. James Ross, D.D.” in Dalhousie Gazette, Historical No. 1903, pp. 114-52; J. Macdonald Oxley, “Some Reminiscences of the Men of ’76,” Dalhousie Gazette, Historical No. 1903, pp. 159-63; Benjamin Russell, Autobiography (Halifax 1932), pp. 48-9. There is a retrospective article on James Ross in the Morning Chronicle, 1 Jan. 1912, and a much better one in George Patterson, Studies in Nova Scotia History (Halifax 1940), “Dalhousie’s Second Principal - an old boy’s tribute,” pp. 100-5. ↵

- The source for much of this paragraph and subsequent ones on Macdonald is the Dalhousie Gazette, Macdonald Memorial issue, Apr. 1901. See also J. Aubrey Lippincott, “Dalhousie College in the Sixties,” Dalhousie Review 16, no. 3, (1936-37), p. 287. Dr. Lippincott graduated in medicine in 1867. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, Historical No., 12 Jan. 1903, p. 161; Dalhousie Gazette, 7 May 1894. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 30 Jan. 1890. See also William B. Hamilton, “William Lyall,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, xi: 534; and Lippincott, “Dalhousie College in the Sixties,” p. 286. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 17 Nov. 1877, 22 Nov. 1895. See also Suzanne Zeller, “George Lawson,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, xii: 539-43. ↵

- Senate Minutes, 17 Mar. 1865, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 1 July, 11 Sept. 1865, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives; Letter from De Mille to Board of Governors, 2 July 1865, from Chester, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 26, Dalhousie University Archives; Letter from Thomson to De Mille, 12 Sept. 1865, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 26, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Patricia Monk, The Gilded Beaver: An Introduction to the Life and work of James De Mille (Toronto 1991), passim; George Patterson, More Studies in Nova Scotian History (Halifax 1941), “Concerning James De Mille,” pp. 146-7; Lippincott, “Dalhousie College in the Sixties,” p. 288. ↵

- I have not found the matriculation examinations for the 1870s. Doubtless they did not differ all that much from the ones given here for 1893-4. ↵

- See Calendar of Dalhousie College and University, Session 1872-1873, p. 20; Senate Minutes, 8 Feb. 1866, Dalhousie University Archives; David Allison, History of Nova Scotia, 3 vols. (Halifax 1916), II: 840-1. Allison was however given an honorary LL.D. by Dalhousie in 1919. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 29 Apr. 1876. This was in a parting address by the students graduating in 1876. ↵

- The Senate rule was laid down on 6 Feb. 1865, but it was not easy to enforce. When the Board of Governors raised the question, the Senate replied, that the existing rules could be “approximately enforced within the limits of the college and the Parade with the aid of a Janitor whose whole time were secured for duties connected with the College.” But since he was not so available, “there is virtually no check upon the conduct of students or others outside the Class-Rooms.” The Senate also noted that the mortar-board was not suitable for winter wear and ought to be modified. For Duncan Fraser’s reminiscences, see Dalhousie Gazette, 25 Jan. 1908, p. 116. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 14 Dec. 1872, “Ragamuffins”; Dalhousie Gazette, 25 Apr. 1870, p. 73. ↵

- The two Pictou County students are described in Kenneth F. Mackenzie, Sabots and Slippers (Toronto 1954), pp. 114-15. This reference has been brought to my attention by Allan Dunlop, to whom I am most grateful. An early rugby game was devised, twenty-five students a side, which was a mixture of rugby and soccer. ↵

- Colin D. Howell, A Century of Care: A History of the Victoria General Hospital in Halifax 1887-1987 (Halifax 1988), pp. 1-34. See also C.B. Stewart’s history of the Dalhousie Medical Faculty in Mail-Star (Halifax), 14 Sept. 1968. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 28 Nov. 1863, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives; see also Howell, Century of Care, pp. 22-3, and Acadian Recorder, 11 Aug. 1875. ↵

- D.A. Campbell, “Medical Education in Nova Scotia,” Maritime Medical News, July 1910, p. 13; and Colin D. Howell, “Medical Science and Social Criticism: Alexander Peter Reid and the Ideological Origins of the Welfare State in Canada” in C. David Naylor, ed., Canadian Health Care and the State: a Century of Evolution (Montreal and Kingston 1992), pp. 26-37. See also Board of Governors Minutes, 12 Aug. 1870, 26 Jan. 1872, 6 Apr. 1872, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Much of the correspondence is in the Board of Governors Minutes. See especially 19 Mar., 26 May, 2 June 1873; 9 July, 16 Sept. 1874, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 5 Feb. 1875, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. It is signed by all nine members of the Dalhousie board: Sir William Young, Charles Tupper, J.W. Ritchie, S.L. Shannon, G.W. Hill, G.M. Grant, J.F. Avery, C. Robson, and Alexander Forrest. ↵

- Halifax Evening Reporter, 11 Mar. 1876; Nova Scotia, Statutes 1876, 39 Vic. cap. 28; Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1876, 10 Mar., pp. 52-3. See Denis Healy, “The University of Halifax, 1875-1881,” Dalhousie Review 53, no. 1 (Spring 1973), pp. 39-56. Pictou Colonial Standard, quoted with approval in Morning Chronicle, 1 Apr. 1881. For Samuel Creelman, see Nova Scotia, Debates and Proceedings of the Legislative Council, 1881, 8 Apr., p. 69. ↵

- I have not found the origin of the delightful alliteration, “Church, Chance or Charity.” It is in the Halifax Evening Reporter of 22 Feb. 1876, in the leading editorial, “The College Question,” and is attributed to Dalhousie or the Presbyterians. Dalhousie Gazette, 31 May 1876, editorial entitled “The College War.” For Lyall’s address to convocation see Dalhousie Gazette, 21 Nov. 1874. Halifax Evening Reporter, 2 Mar. 1876, letter from “One of the People.” The Reporter gave general support to the Hill government. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 1 Apr. 1876. ↵

- A Professor, The University of Halifax Criticised in a Letter Addressed to the Chancellor (Halifax 1877), pp. 3, 5, 6-8, 21. There is no external evidence that Charles Macdonald wrote this pamphlet, but the level of sophistication in both classics and mathematics displayed in the pamphlet strongly suggests his authorship. ↵

- For a fuller gist of MacGregor’s letters, see Healey, University of Halifax, pp. 50-1. On the adventures of the Colleges bill, see Peter Waite, The Man from Halifax: Sir John Thompson, Prime Minister (Toronto 1985), pp. 98-9. ↵

- The sources of financial information for the 1870s are not very satisfactory, for the Board of Governors Minutes are sporadic with financial information. There are only occasional indications of where Dalhousie’s capital (that produced the $3,000 from investments) actually was. Some $8,000 was put into Bank of Montreal stock in 1876. Most of the rest seems to have been in mortgages. The total capital was probably about $75,000. See Board of Governors Minutes, 21 Apr. 1871; 26 Jan., 12 Mar. 1872; 3 Feb. 1876; 19 Mar. 1879, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. The Morning Herald of 23 Apr. 1896 has a long retrospective on Dalhousie, including some useful financial information, some of it written by Professor Archibald MacMechan. For the Dalhousie Alumni Association, see the pamphlet, History of the Dalhousie Alumni Association ([Halifax] 1937), with no author given. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 18 Sept. 1876; 21 Aug. 1879, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- See Walter J. Chute, Chemistry at Dalhousie (Halifax 1986), p. 10; Board of Governors Minutes, 14 Sept. 1877, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives; Board of Governors Correspondence, J.J. MacKenzie to Sir William Young, 6 Dec. 1877, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 34; 13 Apr., 23 June 1878, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 12, Dalhousie University Archives; Letter from Young to Reverend C.B. Pitblado, 28 Sept. 1878, from Halifax, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 12, Dalhousie University Archives; extract from Minutes, Board of Superintendence of Theological Hall, Pictou, 1 Oct. 1878, reported by P.G. MacGregor, secretary; Dalhousie Gazette, 8 Feb. 1879. ↵

- Letter from Young to Pitblado, 26 May 1879, from Halifax, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 35, Dalhousie University Archives. W.L. Grant and F. Hamilton, Principal Grant (Toronto 1904), pp. 187-8. Hilda Neatby, Queen’s University: And Not to Yield: 1841-1917 (Kingston and Montreal 1978), pp. 151-3; Dalhousie Gazette, 14 Dec. 1877. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 20 Dec. 1892, “President Forrest,” p. 141; Dalhousie Gazette, 19 Jan. 1893, letter from “Another Alumnus,” pp. 164-5. ↵