A Brave Beginning, 1816-1821

Lord Dalhousie comes to Nova Scotia. Halifax in 1816. The Castine Fund. Presbyterian rivalries. Lord Dalhousie’s College approved. Scottish educational traditions. Laying the cornerstone, 1820.

Dalhousie Castle lies a dozen miles southeast of Edinburgh, not far from the village of Bonnyrigg, but out in the Scottish countryside, as befits an ancient establishment that dates from the thirteenth century. Of that original building only the foundations and dungeon remain; the main structure now visible was built about 1450, using the salmon-red stone quarried across the South Esk. The castle stands between the South Esk and the Dalhousie Burn that flows into it, two streams where salmon and trout still run.

The rivers flow north in this part of Midlothian. The whole countryside, Edinburgh included, fronting on the Firth of Forth, is backed against the Moorfoot hills and the hills of Lammermoor. The history of this Midlothian countryside is shot through with legend, and with the wars against England. Sir William Ramsay de Dalwolsey swore fealty to the English king, Edward I, at Dalhousie Castle, when Edward stayed there on his way to defeat William Wallace at Falkirk in 1298. The Ramsay family were raised to the peerage in the time of the Stuart king, James VI of Scotland and James I of England (1603-25); that did not prevent the first Earl of Dalhousie from fighting with his regiment in 1644 at Marston Moor, down in Yorkshire, on the side of Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell himself wrote despatches from Dalhousie Castle in 1648, a few months before the execution of Charles I in London in January 1649.

After the Union of England and Scotland in 1707, the Ramsays and other Scots became soldiers in the service of Great Britain. The fifth earl fought in the War of the Spanish Succession, 1702-13; another Ramsay signed the agreement for the surrender of Quebec on 18 September 1759. The ninth earl, George Ramsay, ours, fought with Wellington in Spain in 1812-14, and at Waterloo in 1815. Watching the ninth earl’s panache that terrible Sunday, 18 June 1815, Wellington said of him, “That man has more confidence in him than other general officer in the army.” That confidence was not always justified; the ninth earl’s compaigning in Spain did not earn him accolades from historians, who pictured him as slow and methodical rather than decisive. Yet he must have been well regarded at the time, for during and after the war he received honours from king and Parliament – a KB in 1813, after Waterloo a GCB, and the official thanks of Parliament[1]

All that did not help much to repair Dalhousie Castle, which Lord Dalhousie set about after his return from Waterloo. He got an architect to help restore it to its original form, which cost more than he had readily available. Like many British officers after the Napoleonic Wars, he sought a colonial appointment to preserve his military rank and pension. His idea was to follow Sir John Coape Sherbrooke as lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia and thence as governor general of British North America to which Sherbrooke had been appointed in April 1816. The colonial secretary was Lord Bathurst, the longest serving colonial secretary in the nineteenth century, from 1812 to 1827. His actual title was secretary for war and colonies, a significant combination of responsibilities. He also found it easy to reward service in the Peninsular War with positions in the postwar colonial service. Lord Dalhousie got his appointment to Nova Scotia in July 1816. With his wife and the youngest of his three sons he sailed from Portsmouth on 11 September in HMS Forth, a forty-gun frigate. It was a good passage, via Madeira as was common in westward sailings, and she ran into Halifax harbour on the morning of 24 October. Lord Dalhousie came ashore in state the same afternoon.

Lord Dalhousie took to Halifax and to Nova Scotia almost at once. He liked his house and he noted that the “natives,” as he at first called Haligonians, “good quiet and plain Burgesses, are inclined to show us every attention.”[2] He was forty-six years old, fit, intelligent, and active, driven by considerable curiosity about the world around him. He was a man trenchant of mind and inclined to be authoritarian of decision, though cautious until he had duly weighed up the options. He was experienced and knowledgeable on farming, and was much given to improving old and slack methods in both farming and politics. In his early travels around Nova Scotia he noted much land unfarmed, not because it was not owned, but because the owners did not live up to the terms of the grant, holding it for opportunity to sell it for a fat, but unearned, profit. With the help of Richard J. Uniacke, his attorney general, Dalhousie was able, over the next year or so, to get some 100,000 acres returned to the crown for non-performance of the terms of the land grant.[3]

His quest for knowledge of his domain is detailed in his journal, and it opens up fresh and interesting vistas on the Nova Scotia of 1816-20, a period not otherwise well served by newspapers and other records. Nothing seemed to give Lord Dalhousie more satisfaction than to mount his horse and explore the Nova Scotian countryside, or to get the admiral on the Halifax station to take him on a voyage around the coasts. Sometimes, as in 1817, he combined both, taking a naval ship around to Pictou, and then riding back to Halifax via Truro. Few governors have been so assiduous at seeing and describing their colony. And he grew to be very fond of it. He wrote to Sir John Sherbrooke, now governor general of British North America, in June 1818, “a more quiet, contented and kind people does not exist, nor can there be a more interesting situation than that which sees a beautiful country and a happy people bursting into prosperity by hard labour.”[4]

Nova Scotia had a population at that time of some eighty thousand of mixed origins; Lunenburg County’s German settlers came there in 1753, but otherwise the inhabitants of the South Shore and the Annapolis valley were of Yankee background, from both before and after the American Revolution. As Sam Slick once said, those parts were “near about half apple sarce, & t’other half molasses, all except to East’ard, where there is a cross of the Scotch.”[5] In religion they were Baptists, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians; the new waves of immigrants that came after 1815 were also Methodists, Catholics, and various splintered branches of Presbyterians. Only one-fifth were Anglicans, and the proportion would get smaller; Nova Scotia was on the eve of a considerable expansion of population that would rise by the 1850s to three hundred thousand.

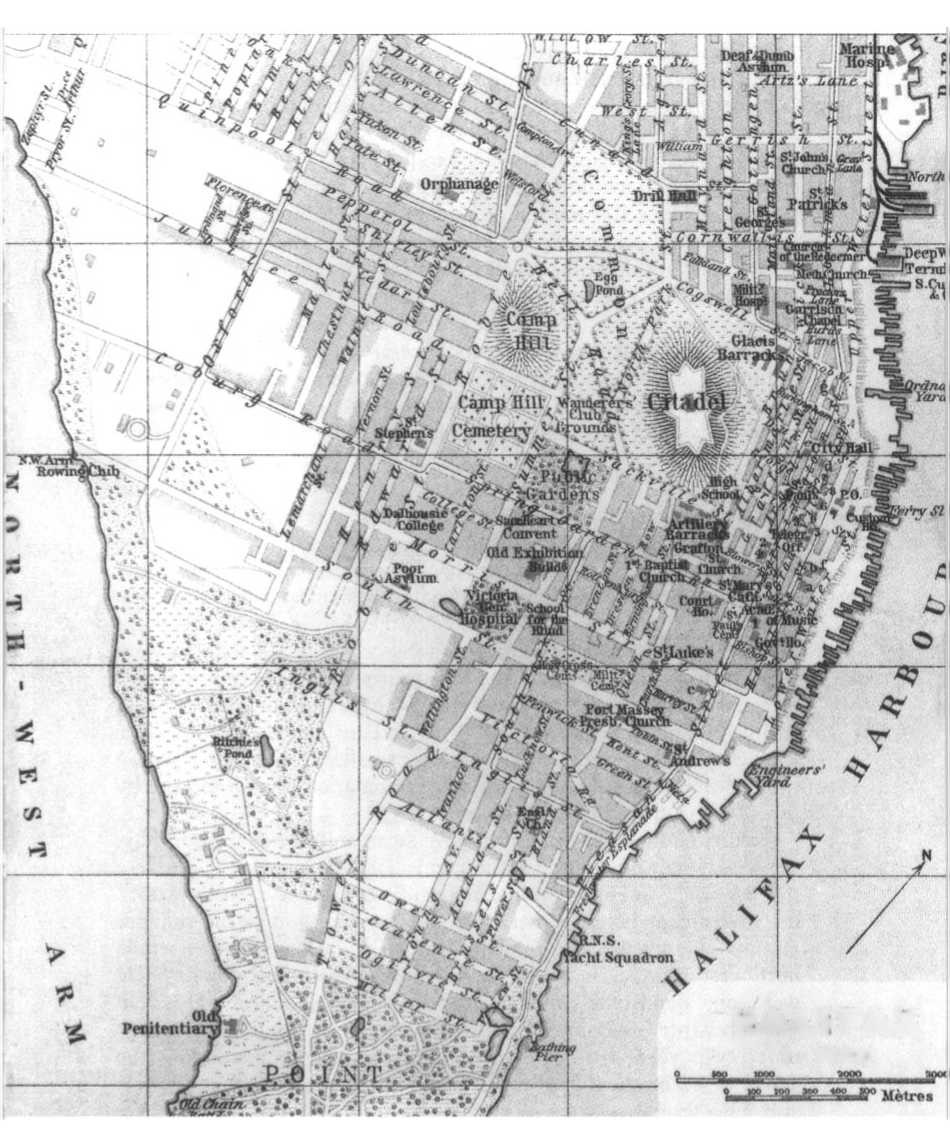

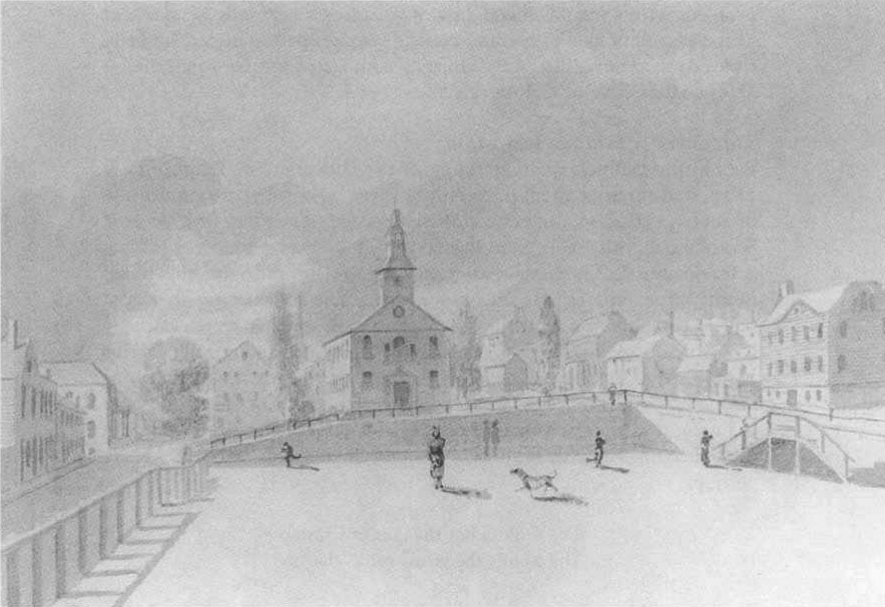

Halifax had a more pronounced Anglican and British flavour, having both a major military garrison and a large naval base. There were troops enough in Halifax to line both sides of the street from the dock to Government House when Dalhousie arrived, and in the summer months Halifax was the principal British naval base for the whole northwest Atlantic. (In winter they sensibly moved to Bermuda.) There were some handsome buildings already in place: Admiralty House in the dockyard; Government House, finished in Sir John Wentworth’s time seven years before; Province House under construction; the Town Clock on the side of the Citadel Hill. The hill itself, at 275 feet above sea level, was some twenty feet higher than it is now; it had yet to undergo the big renovations of 1828-60. Halifax was also a city of churches. There is a handsome watercolour painting of Halifax by an unknown artist done for T.C. Haliburton’s 1829 history of Nova Scotia, the artist having set up his easel just above Dartmouth Cove. Below the Citadel, the steeples marked the skyline of the town: to the left, St. Matthew’s Presbyterian; then St. Paul’s Anglican, the style and construction taken straight out of Boston, literally in pieces, in 1750; then the Town Clock, and finally, on the right, the round church, St. George’s Anglican, that reflected the taste of the Duke of Kent.[6]

Halifax was a town of great contrasts – an amalgam of military, naval, governmental, and commercial enterprises, all gathered together around a large and spacious roadstead. The town itself had been founded only seventy years before. The opulent and the poor, the stone buildings and the wooden ones, lived side by side; social and economic segregation did not yet exist. The town still got its water from wells; in 1817 the Halifax Water Company was formed to supply the town with water by pipes, from a reservoir on the Common. It failed, however; Halifax would get water mains in the 1840s. In 1818 the Assembly passed an act establishing a watch at night in Halifax “for the better preservation of property.” A few years later the Assembly passed a traffic act. No one was allowed to gallop a horse on any public highway in Halifax or any other town faster than “a slow or easy trot.” Sleighs in winter were to have bells (otherwise you could not hear them coming), and everyone was to drive on the left hand side of the road.[7]

There was a good deal of military and naval pomp and ceremony in Halifax. When Lord Dalhousie’s ship left Halifax three weeks after his arrival, she was saluted officially as she made her way down the harbour. Lord Dalhousie rode down to Point Pleasant to watch:

The scene was very beautiful – the Grand Battery [the Citadel], George’s Island, Fort Clarence [Dartmouth at Eastern Passage], Point Pleasant, followed each other. The Forth was then abreast of the North point of McNab’s island, hove to & backed her topsails, so as to lay herself right across the stream, returned the salute, in the most magnificant style, & then filling handsomely stood down to York Redoubt where the Battery again saluted her.

But there were other sides to military life. Alexander Croke, a viceadmiralty judge in Halifax from 1801 to 1815, irascible, conservative, and literary, poked fun at wicked Halifax, all in heroic couplets. A Halifax party in 1805:

Great Harlots into honest Women made, And some who still profess that thriving Trade; Great Accoucheurs, great Saints and greater Sinners, And all who love great Dances and great Dinners; Great Ladies who the chains of home despise And Pleasure’s Call above decorum prize; Red Coats, and Blue Coats altogether squeeze Buzzing and humming, like a Swarm of Bees.[8]

It was only twenty years since Prince Billy (to become William IV in 1830) and his ADCs could drink themselves under the table at Government House. Gentlemen who could manage it went up to visit the brothels on Citadel Hill, concentrated on the two upper streets, Barrack Street (now Brunswick), and Albemarle (now Market). It was a drinking society at all levels. Lord Dalhousie noticed in his travels around Nova Scotia heavy indulgence in rum, especially in the evening when the farm labourers were coming home, “staggering along the roads, noisy & roaring like ill-doing blackguards.”[9]

It was a rough and violent society. Richard J. Uniacke’s son killed a Halifax merchant in a duel in July 1819. His father, as attorney general, could not prosecute, but told the court that whatever his feelings, they must be subservient to the laws of the land, which he was sure would be administered with both justice and mercy. Young Uniacke got off, but the episode shocked the city, and it began the trend away from duelling.[10] It was not the end of it, however; Joseph Howe was compelled to fight a duel in 1840, but it ended without either antagonist being hit. Howe’s opponent missed; Howe, a good shot, fired into the air.

Halifax had been a war town built out of the discovered necessities of one war – the War of the Austrian Succession – and in preparation for others; the Napoleonic Wars with France and the War of 1812 with the Americans were fresh in the minds of every inhabitant. It was only three years since young Thomas Chandler Haliburton slipped from the afternoon church service at St Paul’s to run down to the waterfront to see HMS Shannon with the captured USS Chesapeake behind her, sailing past the Halifax wharves to anchor at the dockyard. The commander of the American ship, Captain James Lawrence, died in Halifax of his wounds, and was buried in St Paul’s cemetery with full military honours a few days later.[11]

Effects of the War of 1812

The aftermath of the War of 1812 in Nova Scotia fell on Dalhousie’s predecessor, Sir John Sherbrooke, a fellow officer from the Peninsular War. Wellington thought highly of him. “Sherbrooke is a very good officer, but the most passionate man I think I ever knew.”[12] Sherbrooke had become lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia in 1811. When Napoleon abdicated in April 1814, the War of 1812 against the Americans took a new and decisive turn. British troops were sent across the Atlantic, and some of them came to Halifax. On instructions from Lord Bathurst, the colonial secretary, Sherbrooke was told to occupy “so much of the District of Maine as will ensure uninterrupted communication between Halifax and Quebec.” Sherbrooke believed that it would be done best by control over the Penobscot River. That in turn was determined by possession of Castine, a small port that lay right at the mouth of the river on the east bank. Sir John Sherbrooke put together a small fleet of warships and transports and brought two thousand British regulars from Halifax. Castine gave up with hardly a shot being fired, and this was followed a few days later by the surrender of Bangor. Maine from the Penobscot to the St Croix was soon in British hands.

British military administration of the territory was mild and gave little offence to the inhabitants. American laws were left in place, administered by American justices of the peace. Castine became the main clearing port for the whole district. The customs rules were the same as those that obtained at Halifax. The Peace of Ghent in December 1814 required the evacuation of the British, which they duly complied with in April 1815, bringing the Castine money with them to Halifax, some £12,000 Halifax currency.[13] Lord Dalhousie described it as a large sum of money, the spending of which would certainly need mature consideration.[14] The story has been set down in poetry by Archibald MacMechan, in “The Castine Fund”:

Sir Johnny Coape Sherbrooke’s the hero I mean, He sail’d off and captur’d the town of Castine, The Yankee head-centre for smart privateers That had bothered our merchants for nearly three years.

And six months Sir John in that port did remain Saving work for collectors of customs in Maine, When peace was declared and the war it was o’er With ten thousand pounds he sail’d back to our shore.

The Earl of Dalhousie was governor then, The bravest and wisest of Scotch gentlemen, He said, “With this money we got at Castine We’ll found the best college that ever was seen.”

Now the ends of the earth and the province have heard How well and how wisely my lord kept his word; And on the Parade, where the grass it grows green, He built old Dalhousie with funds from Castine.[15]

Sherbrooke turned over the money to the imperial treasury in Halifax. Military man that he was, he was a little puzzled what best to do with it. The colony had no public standing debt to be discharged; Sherbrooke’s own inclination was towards public works. There was no time, however, to decide upon so weighty a matter, given the slow sea communications between Halifax and London. Thus it remained for Dalhousie to decide. Sherbrooke had left suggestions; a possible Shubenacadie canal, that would open water communication between the south and the north shores of Nova Scotia; an almshouse; a work- house.[16] Dalhousie noted these ideas.

Within a week of his arrival in Halifax, at a meeting of his Council on 31 October 1816, he asked for an official statement as to the actual amount of the Castine duties and where the money was. The amount was £11,596 and it had been credited to the British government by the commissioner general.[17] A few months later, on 20 February 1817, Dalhousie asked his Council for their suggestions. They were numerous and diverse. S.S. Blowers, president of the Legislative Council and chief justice of Nova Scotia since 1797, suggested the canal or an almshouse; he also suggested a form of shopping mall on the Grand Parade, a colonnade with shops inside it. The Anglican bishop suggested an almshouse. Michael Wallace, the provincial treasurer since 1797, offered no opinion. Of the views around the Council table that day, R.J. Uniacke alone suggested the possibility of a new college.[18]

Lord Dalhousie kept his own counsel, planning to bring down a matured scheme in due time. An almshouse was certainly something the Assembly could well provide for. A few months later Lord Dalhousie wrote to Lord Bathurst:

I would earnestly entreat your Lordship would not require me to appropriate the sum of Castine duties to this purpose [roads and bridges], it would go little way & would soon be lost sight of, whereas there are two or three objects of the highest importance to the Province which that sum would cover & prove of lasting benefit to the Province; but I am not yet sufficiently decided which of these objects to recommend to be adopted. I shall report in the course of the Summer.[19]

Dalhousie’s first idea was to spend the money bringing King’s College to Halifax. King’s had been founded in 1789 at Windsor, Nova Scotia, far from the wickedness and garrison glitter of Halifax. With a good show of unanimity, the Assembly had voted £500 to buy the property at Windsor and £400 sterling annually in perpetuity for the college’s upkeep. King’s got a royal charter in 1802 and with it an annual grant of £1,000 from the imperial Parliament. Its charter compelled all its students to keep terms of residence and to subscribe on graduation to the thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England. The more Lord Dalhousie learned about King’s the less he liked it or the idea of moving it to Halifax. In September 1817 he made an official visit to the college, attending the annual meeting of the Board of Governors. He was much displeased. The president and vice-president were the only professors and they were in violent and open war. The Board of Governors’ proceedings were mostly, Lord Dalhousie noted, recriminations, “extremely indecorous and unpleasant.” There were only fourteen students, who liked the mild and agreeable vice- president, William Cochran, and hated the strict and ill-tempered president, Charles Porter. They were ill-disciplined generally, riotous in their rooms and amusing themselves, when not at lectures, in careering about the countryside on horseback. They played tricks even on the bishop, their official Visitor. Bishop Inglis came out after one such visit to discover the tails of his horses had been given a close haircut, hanging lugubriously behind them “like a new washed pudding.” The state of the building was “ruinous; extremely exposed by its situation, every wind blows thro’ it … The expense of living is very heavy, as there is no butcher market or fish [market] at Windsor. In short there are a thousand objections to it.”[20] Although Lord Dalhousie was not in a position to note it, students were educated somehow, on the principle that good students can work almost any system. A few, such as Thomas Chandler Haliburton (BA, 1815) and E.A. Crawley (BA, 1820), were of ability and distinction.

Altogether, Dalhousie’s visit persuaded him that there was no good in importing such an institution, with such a charter, into Halifax. It would merely transfer its problems and its exclusivity from one place to another. Besides, a residential college with walls around it, either literally, or metaphorically from having strict terms of residence, was not at all what he wanted. What he had in mind was quite different. It could not be grafted onto that King’s root; it would have to be developed from the beginning, with its own roots.

There was another institution Lord Dalhousie had to consider, chartered a few months before he arrived – Pictou Academy. In Pictou County, Presbyterian clergymen, in addition to their regular duties, often instructed promising boys in the branches of higher education. Pictou Academy grew out of this ethos and out of the energy and talent of Thomas McCulloch. He had arrived in Pictou in 1803, a minister sent from Scotland; he soon came to the conclusion that Nova Scotia would not be able to wait for those few ministers from Scotland who were willing to endure the trials of life in the North American woods. The colony would have to grow her own ministers.[21]

The upshot was a request to the Nova Scotian legislature in 1815 asking for the right to exist as an academy with no denominational restrictions. The Anglicans who controlled the Council did not like the look of it; it struck them as the beginning of open competition with King’s and the Anglican establishment. The Council cleverly (or diabolically, as some thought) amended the act of incorporation so that the trustees of Pictou Academy had to be either Anglicans or Presbyterians. Since Anglicans presumably would not wish to be trustees of such an institution, Pictou Academy was in effect hived off as Presbyterian. The friends of Pictou Academy in the Assembly deplored this result, but they had no choice; they had either to accept the amendments or lose the bill altogether. Under these circumstances Pictou Academy opened in 1818. It began to look and act like a college – its students were soon wearing the red gowns and caps familiar to McCulloch from the University of Glasgow – but the academy had not, as yet, asked for or received the right to grant degrees.

Lord Dalhousie did not think much of Pictou Academy’s aspirations to become a college. His preliminary opinion was reinforced when he visited Pictou in September 1817, and discovered to his surprise that Pictou was not the considerable town represented to him but a very inconsiderable village. He later told Edward Mortimer, the chief magistrate of Pictou at whose house he stayed, that a non-denominational college was very desirable for Nova Scotia, “but not in a distant corner of it, at Pictou.”[22]

Dalhousie’s attitude was shaped by his strong sense of reality, of what was possible. Pictou was, it is true, the centre of a vigorous, litigious, not to say combative Presbyterian community, with the Scottish drive for education both in its ministers and its adherents. But the academy could never acquire, as far as Lord Dalhousie could make out, the weight of population needed to sustain the form and the life proper to a college.

But there was something else. Presbyterians were anything but united. Scottish immigrants to Pictou imported into their settlements in the new world the rich feuds that had marked the old one. The splits and rivalries within the Presbyterian church were not about theology but over the relations between church and state. The first major split developed in 1733 over lay patronage. Who had the final authority to appoint a minister to the living – the lay patron of the district whose lands had helped to subsidize the church or the congregation? In case of dispute, who had the last word?

The Seceders broke away from the Kirk of Scotland on that issue in 1733. Within a decade the Seceders themselves split over the burgess oath: was it lawful or sinful to take the oath required in certain Scottish cities subscribing to the Presbyterian church by law established? Thus came into existence the Burghers (those who did so subscribe) and the Anti-Burghers (those who did not). The Seceders, of both persuasions, were men of sturdy independence; their ministers were often men of humble origin who had been subsidized by their parishes into schools and universities.[23]

Thomas McCulloch was one of these, a Seceder and Anti-Burgher. This group gradually became more numerous in Pictou County, simply because the ministers of the official Church of Scotland, the Kirk, were anything but enthusiastic about emigration to the wilds of North America. In Nova Scotia the two Seceder branches, the Burghers and Anti-Burghers, united in 1817, forming the Presbyterian Church of Nova Scotia. The Kirk Presbyterians called themselves the Church of Scotland.

There was no love lost between the Kirk and the Seceders. In Scotland, the Kirk was composed in the main of moderate, easy-going, civilized men of quiet, unostentatious piety, and often considerable culture. The Seceders were strong on zeal and messianic fervour, but tougher and more strenuous altogether. It was not surprising that more Seceder ministers had come out to Nova Scotia. Those few Kirk men who were in Nova Scotia were apt to be much less gentle and civilized; some were fierce and rabid partisans. They were also Conservatives whereas the Seceders were liberal, sometimes radical. They would become a driving force, when the time came, behind the Reformers of the 1830s.

McCulloch was against the Kirk and much that it stood for. He came to the view that Nova Scotia would have to prepare her own ministers, and began to teach a small select group of students divinity. It was, naturally, anti-Kirk divinity. The Kirk men were thus anti-McCulloch and anti-Pictou Academy.[24]

McCulloch was not a great preacher; he did not have the Gaelic, as his great friend and contemporary, James MacGregor, did, and that in Nova Scotia where Gaelic was much spoken. McCulloch’s strength lay in his scholarship; his writing was sinewy, biting, polemical. He himself was apt to be testy and difficult. He was not one who “accepted a few dinners and became a harmless man.”[25] Those social seductions were not for him. He relished a fight. He had taken on the Roman Catholics a decade before and published his outspoken convictions on that subject. He fought the Kirk with the same indefatigability. For a man of allegedly indifferent health, McCulloch had a fund of energy. Lean and hard, he drew adrenalin from the vitality of his hatreds: the Kirk, cant, hypocrisy, indifference, and pretence. He was a tough man with a fund of sarcastic humour, even about himself. “Like a beast in winter,” he once told his Glasgow friend James Mitchell, “I am living on my grease and that as you know is not very abundant.”[26] Little grease, little oil, only a bare minimum of hypocrisy, Thomas McCulloch was a formidable antagonist.

Origins of Dalhousie College

These were the circumstances of Nova Scotian education that Lord Dalhousie had to consider in thinking about a new institution in Halifax. He brought the whole question before his Council in the form of a draft despatch to the colonial secretary on 11 December 1817. Lord Dalhousie dismissed earlier suggestions by Sherbrooke and others for eleemosynary institutions. They were admirable enough in their way, but they seemed to Dalhousie to “rather offer a retreat to the improvident than encouragement to the industrious part of society.” There spoke the Scot! Nor would moving King’s from Windsor to Halifax help.

At Edinburgh University professors were appointed at modest salaries, with the privilege of lecturing to any who bought an admission ticket from the professor. Such classes were open to all sects of religion, to strangers spending a few weeks in town, to the military, the navy, to anyone in fact who wanted to spend a useful hour or two during the forenoon. The Edinburgh system made professors both diligent and interesting,

as on their personal exertions depend the character of the class and of the individual himself who presides in it. Such an institution in Halifax open to all occupations and to all sects of Religion restricted to such branches only as are applicable to our present state and having power to expand with the growth and improvement of our society would I am confident be found of important Service to the Province.

Lord Dalhousie proposed £1,000 of the fund to improve and extend the library of the British garrison. It was, after all, the Nova Scotia command that had produced the Castine fund in the first place. The rest, £9,750, would go to support a new college. Lord Dalhousie proposed to put up £2,000 to £3,000 at once to begin a building, leaving the rest as a fund which, duly invested, would produce interest annually to pay professors. He expected that the Nova Scotia legislature would in due time provide a grant matching this annual income. The site for the college would be the Grand Parade. Any present military use he proposed to move to the immediate area of the barracks.

Lord Dalhousie proposed a small interim Board of Trustees, men in Halifax who would be accessible by virtue of offices already held: the lieutenant-governor himself, the chief justice, the bishop (Anglican, of course), the treasurer of the province, and the Speaker of the Assembly. This selection had some obvious weaknesses; three of those dignitaries were already on the board of King’s College and might be said to have prior interests. All of them were busy men. But it was not as casual as it looked. Lord Dalhousie already knew how difficult it was to convene meetings in Windsor of the King’s College board; one of his chief concerns was that the officers of the new college would be accessible and in Halifax.

The clear point of beginning of a university is not always easy to discern; but Dalhousie College (it did not yet have this name) does have a precise one: that submission of Lord Dalhousie to his Council of 11 December 1817. The eight members of Council gave it their unanimous approval, and it was so entered upon the minutes.[27]

The despatch that went to Lord Bathurst three days later varied only slightly from that submission. To the trustees Lord Dalhousie added the minister of St. Matthew’s, the Kirk of Scotland church in Halifax. The Grand Parade he defined as “that Area in front of St. Paul’s Church.”[28] Lord Dalhousie elaborated in writing to Sir John Sherbrooke. The actual college building, he said, would be at the eastern extremity of the Parade, facing St. Paul’s Church; but the foundations would of course be down on Duke Street; there shops would be set up, to be leased out and which would provide some modest income for the college. (It was in effect an early version of the present Scotia Square.) Lord Dalhousie envisaged a single-storey stone building. Sir John Sherbrooke was enthusiastic; a purpose “so judicious,” he said, “cannot but help meet with the approbation of the Secretary of State.”[29]

It did. Lord Dalhousie’s suggestions Lord Bathurst laid before the supreme authority in Great Britain, the Prince Regent, acting for the incapacitated King George III. The Prince Regent had extravagant habits and a flamboyant taste; once a handsome young man, by 1818 he was gross and fat from years of indulgence. Nevertheless, he had great love for the arts; Brighton Pavilion was rebuilt by him after 1817, and still stands as a remarkable achievement by the Prince Regent’s architect, John Nash. That, Regent’s Park, and Regent Street, represent only a part of Nash’s work under the Prince Regent’s lavish if idiosyncratic patronage. The prince’s approval of the college proposed for Halifax must have been nearly immediate; Lord Bathurst’s despatch is dated 6 February 1818, and it may be properly set down as the official beginning for Dalhousie College:

having submitted them [Lord Dalhousie’s proposals for a College] to the consideration of the Prince Regent, His Royal Highness has been pleased to express his entire approbation of the funds in question being applied in the foundation of a Seminary in Halifax, for the higher Classes of Learning, and towards the Establishment of a Garrison Library.

That despatch arrived while Lord Dalhousie was in Bermuda in April 1818, but on his return he was delighted to find that the founding of a college in Halifax had such prompt and unequivocal approval. He asked Council for suggestions in framing a charter for the college, and it was agreed to submit a draft to London. In the meantime work could be started in laying out the ground.[30]

Lord Dalhousie lost no time in seeking information and support from the one quarter he best knew, the University of Edinburgh. He had attended it himself as well as the Edinburgh High School, where he had sat beside the young Walter Scott. Dalhousie never took a degree; in 1787 when he was seventeen years old, he felt obliged to take up a military career after the death of his father. He now solicited the views of an Edinburgh professor of belles lettres who knew Halifax well, the Reverend Dr. Andrew Brown. Brown had come to Halifax in 1787 as the Kirk minister for St. Matthew’s Church, where he stayed for eight years. A brilliant preacher and a leading figure in Halifax society, he did much to try to heal the divisions among Presbyterians. He was well known in Nova Scotia and in the United States as a historical researcher, a scholar unusual for his time in sympathizing with the Acadians. Returning to Scotland in 1795, he travelled back in the same ship as Prince William (later William IV) and so impressed him that the prince recommended him for the Regius Professorship in Rhetoric and Belles-Lettres when it became open in 1801.[31]

Lord Dalhousie wrote to Brown asking him to deliver a letter enclosed to the principal of Edinburgh University, Dr. George Husband Baird, also asking for information and suggestions. Dalhousie explained to both men the current state of Nova Scotian education, the problem with King’s College, how it operated to exclude 80 per cent of the population. The Halifax college would operate under the principles of the University of Edinburgh, with lectures open to all the religions admissible at Edinburgh.[32]

Traditions of Scottish Education

Behind the character and standing of the University of Edinburgh in 1818, and other Scottish universities, there lay a substantial tradition of Scottish religion and education. The essential element of it was the Scottish belief that everyone should have his chance. Going to school was something as important as going to church on the Sabbath, valued as much for itself as preparation for work. The Scottish parish school helped to define the worth of the student in ways that were relatively independent of class and circumstance. John Locke’s argument in his 1690 Essay Concerning Human Understanding that man is born as tabula rasa on which was written experience may have been accepted in England as a philsophical principle; in Scotland that idea came from other origins – parish schools, Presbyterianism, oatmeal and whisky perhaps,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp The Man’s the gowd for a’ that…

There is much in Robert Burns’s “The Cottar’s Saturday Night” that speaks to this argument:

From scenes like these, old Scotia’s grandeur springs, That makes her lov’d at home, rever’d abroad, Princes and lords are but the breath of kings, “An honest man’s the noblest work of God.”[33]

In the lecture halls of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, and St. Andrew’s this came to be a democracy of the mind – that a man’s intelligence was what mattered and it should have opportunity to develop. It was not a doctrine for the weak, the lazy, or the faint-hearted: hard work was, the Scots believed, good for minds, as exercise and stress was for muscles and bones. It was achievement that signified.

The beginning of this process of education, the parish school, was expected among other things to prepare an elite for the university and the professions. It provided the necessary instruction in Latin, but it joined to that such utilitarian subjects as surveying or bookkeeping, while still keeping the basic focus on intellectual and moral training. The effect was to allow recruiting of business and the professions from a wider cross-section of the population than in England, enough to justify the pervasive expectation that careers were open to talent.

The Scots had early organized a system of scholarships that opened their universities to good students. As a start it was essential to recruit for the ministry. Every presbytery that contained at least twelve parishes was obliged by a 1645 law to provide an annual scholarship. It did not meet all a student’s expenses; it enjoined frugality; but a poor student could manage by ekeing out his resources with summer work as tutor or farm hand. Entrance examinations were unknown at most Scottish universities. Students were tested in course.

Compared to English universities, the classics were neglected; but because classics did not occupy the central position they did in Oxford or Cambridge, university education in Scotland had a more philosophical, scientific character. It is not surprising that alone in Great Britain the Scottish universities possessed original schools of philosophy. By 1800 the dominant theme of them came to be called the philosophy of common sense, rejecting the metaphysical conclusions of Bishop Berkeley and David Hume.[34]

Philosophy was thus the first of the university subjects which Scottish students got their teeth into, their first big adventure in university. If, in doing ethics on the one hand and logic on the other, students got a double dose of philosophy, the Scottish view was, so much the better.[35]

Philosophy of course included natural philosophy – that is, science – and the Scots did much with that. It was entirely reasonable that Thomas McCulloch’s interests comprehended theology and medicine and science. His range owed much to his natural genius, but not a little to his philosophical training at the University of Glasgow.

There was a wholesomeness, a vitality, an intense empirical curiosity about these Scottish intellectual traditions. That was what Lord Dalhousie was thinking of when he sought advice from Andrew Brown and George Baird. He received a long reply signed by both men, though written by Andrew Brown, giving a history of the university, how it began with one professor in 1583, and grew as need and funds allowed. As to qualifications for admission, Baird and Brown made clear,

The Gates of the University are open to all persons indiscriminately from whatever Country they may come or to whatever modes of faith or Worship they may be attached. In fact we do not know that any other disqualification for admission to the privileges of the University exists, than the brand of public ignominy or a sentence of Expulsion passed by another University. Nothing further in the shape of pledge or engagement is exacted from the general Student, than that he take the Sponsio Academica, binding himself to observe the regulations relative to Public Order, to respect his teachers, and maintain the decorum becoming the character of a Scholar.[36]

They saw advantages in Halifax for teaching by volunteers in professional fields such as law, medicine, and religion. The University of Edinburgh’s experience was decidedly in favour of the principle of private lecturing; at Edinburgh, far from being injurious to full-time professors, private voluntary lecturers tended to augment the number and the range of students.

Baird pointed out in a private letter written shortly after that the University of Edinburgh had no power to nominate any of its own professorships: “This total want of power and patronage, I hold to be, without exception, the greatest excellence of the University system. Give the Senatus academicus a right to these and on every vacancy there would be party canvassings and contentions excited which would be equally destructive of our peace, comfort and prosperity.” Thus, while Senate ran the internal affairs of the university, the election to chairs and professorships should be vested either in the crown or in some body totally distinct from the college itself. There was much good sense in this; the in-fighting over professorial appointments at Oxford and Cambridge was well known even then.

Professorial salaries at Edinburgh were quite modest. The professor of chemistry was paid only £30 year. But he drew fees from students; in the 1817-18 session he had five hundred students, and thus his gross income, at two thousand guineas, was more than adequate. Of course Halifax could not produce nearly as many students, and the salaries paid to professors would have to be much more generous; still, Baird said, “your Lordship will not lose sight of the importance of allowing a Professor to depend in some degree on the popularity required by his learning [,] talents and exertions.”[37] That idea was salutary for all professors.

Andrew Brown knew a good deal more than Baird about Halifax. He was sure, he wrote Lord Dalhousie, that only a literary institution like a college would promote classics, science, and religion in Halifax. But it was important to remember that the University of Edinburgh was basically at arm’s length from the Kirk. The university left religion up to the students, except for those in theology. It made no attempt to determine how students should spend the Sabbath; it had never even had divine service within its walls.[38]

Starting the College Building

Lord Dalhousie submitted most of this correspondence to the trustees of his proposed college – it was called St. Paul’s College for a short time – and at the same meeting on 12 November 1818 he produced three different sets of plans for a building. Under Lord Dalhousie’s directions an architect, a Mr. Scott, was to be employed to prepare a final set of plans embodying, as the board saw it, the best features of each. A month later a minute of Council formally registered the handing over of the Grand Parade as the site and grounds for the new college.[39]

The Grand Parade had been reserved for militia purposes when the town was laid out in 1749, though it had never been military property as such. Locals did not much like it; they felt it got in the way of progress up and down George Street. Paths across it were inevitable. One went on an angle, from George Street across down to the comer of Duke and Barrington streets, descending in its last fifty yards very abruptly. When the Duke of Kent was general commanding at Halifax from 1794 to 1798, he had had the Parade levelled off by having support walls built along the sides facing Duke and Barrington streets. Thus the corner of the two streets was some fifteen feet below the level of the Parade. Those support walls were built with space behind them, used for storing ice. To put a college building at that northern end of the Parade required some structural reinforcement to support the weight of the building and to develop shops from ice houses, but no major changes of alignment and scale were needed.

The session of the legislature of 1819 was the first in the new Province House, which had been under construction since 1811. Lord Dalhousie delivered the Speech from the Throne on 11 February, in the Council chamber, under the portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte. He congratulated the legislature on their meeting for the first time in such a handsome building, and hoped that Nova Scotia, “this happy country,” would continue to be blessedly ignorant of the influence of party or faction. After all, the purpose of any legislature, was “the prosperity, the improvement, the happiness of the land you live in.” Lord Dalhousie emphasized improvement, but roads and bridges – an Assembly preoccupation – was not Lord Dalhousie’s idea of what improvement really meant. “I will submit to you the plan of an institution at Halifax in which the advantages of a collegiate education will be found within the reach of all classes of society, and which will be open to all sects of religious persuasion.”[40] By April the Assembly had agreed to match Lord Dalhousie’s £3,000 of Castine money, reserved for building, with £2,000 of its own. It professed its warmest thanks for Lord Dalhousie’s initiative and hoped that “this Institution may flourish, and continue to the Inhabitants of Nova Scotia a lasting monument of the enlightened policy of Your Excellency’s administration.”[41]

The Royal Gazette of 28 April solicited tenders for supplying the “best iron rubble stone, best white lime, and hard fresh sand” for a building at the north end of the Parade, and for tenders for the masonry work. Plans were available for inspection at the office of Michael Wallace, the provincial treasurer. Wallace had had considerable experience in building; he had been the official mainly responsible for the elegant but costly work on Government House, and was on the committee for building Province House. He was old-fashioned in dress and style, irascible, always on the boil about something, and very much at the centre of things in Halifax. He was connected closely with King’s College; he sent his sons there, and married off his daughter Eleanor to President Charles Porter in 1808.[42] He had already been authorized, in March 1819, to buy square timber for construction and there was £5,000 to build with. Given the prices that prevailed in Halifax after the war, that might not go far enough. But Dalhousie was confident that that sum, with £7,000 invested in British Consols, and with a promise of £500 a year from the Assembly, would make a substantial beginning.[43]

In December 1819 the interim Board of Trustees officially applied for a royal charter for the Halifax College, as it was now called. The rules would be those of the University of Edinburgh, in principle taken from the Baird-Brown letters of 1818. Three professors, it was expected, would be appointed, in classics, mathematics and natural philosophy, and moral philosophy. The papers covering this were despatched to the Nova Scotian agent in London, Nathaniel Atcheson, who was instructed to get Bishop Robert Stanser, the only trustee not in Halifax, to sign the official application as the others had done. Bishop Stanser was then on the Continent, but returned to London early in January 1820. The proposal to establish a college at Halifax, and the fact that he was nominated to its Board of Trustees, came to the absentee Anglican bishop as a complete and painful surprise. He would not sign the requisition. As a governor of King’s College he was bound to King’s; he had been reliably told that King’s was in “a ruinous state, and that Funds are immediately wanted for an entire new Building,” and he was bound, as official Visitor, to take cognizance of that fact, above all else. He would sign nothing for a Halifax college. So the request to the secretary of state went forward without the signature of the Bishop of Nova Scotia.[44] Though nominated to it, he was never to be a member of the board. That was both a reality and a symbol.

Royal charters were a gift of the crown, but they came with fees for engrossing, sealing wax, and parchment. King’s had paid £370 sterling for its charter in 1802; Halifax College would require something like £570 – that is, about £700 currency. When Lord Dalhousie heard that, he and his board called off the royal charter. The price was too heavy; they had better things to do with that kind of money. The building was going to be rather more expensive than expected; it would be cheaper to allow the Halifax College to be established under a simple statute of Nova Scotia.[45]

Lord Dalhousie also sought suggestions, indeed nominations, from Professor James Henry Monk of Trinity College, Cambridge, Regius professor of Greek, for a principal for the Halifax College. The same growing perception of limitation of means animated this request; instead of three professors proposed six months before, it was now, for the moment at least, only one, who would be principal and would combine the teaching of classics and mathematics. The salary offered was £300 a year, with the prospect of it being doubled by fees. The college was now being built, Lord Dalhousie said, and might be ready by December 1820, but the new principal would not be needed before March or April of 1821. The building, though large, would not have accommodation for staff or students, but house rents in Halifax were moderate.[46]

By this time, May 1820, Lord Dalhousie’s own career had taken a new turn. He had been bitterly disappointed, indeed extremely angry, when in May 1818, contrary to promises made by Lord Bathurst, the governor generalship of British North America had gone to the earl’s impecunious brother-in-law, the Duke of Richmond. Dalhousie was deeply chagrined, and wrote the colonial secretary accordingly: “I have now served my Country 21 years, chiefly on foreign service, I have followed up a Military life without shrinking from any duty or any climate, I have sacrificed every comfort of an independent fortune, every happiness that man can desire in his family … to serve my Country with distinction.” He privately decided that he would serve out his term in Nova Scotia, then retire to Scotland. So he told the Duke of Richmond when on a visit to the Canadas in the summer of 1819.[47] Then in August 1819, when hunting near Sorel, the Duke of Richmond was bitten by a fox. The wound healed, but the rabies he received began its terrible work, and he died agonizingly a few weeks later.

Lord Dalhousie heard the news in Halifax. He made no representations to London; he let the British government decide whether he would go to Lower Canada as governor general or retire to Scotland. He knew enough of the Canadas by that time to suspect that governing them would not be easy. He was told of his promotion in late November 1819; Quebec was quite inaccessible until May 1820, and he was content to winter in Halifax. There were things to be settled, not least the reannexation of Cape Breton to Nova Scotia that had already been decided in London. Basically he was pleased with his sojourn in Nova Scotia and with his work; he could deliver his province to his successor without any basic problems. It was “overflowing with the necessaries of life, and roused to a spirit of Industry that gives the fairest promise of happiness and prosperity.” So he told himself in his journal.[48]

There would be some vexations to come in the session of 1820. But in his prorogation speech on 3 April 1820, Lord Dalhousie was able to point proudly to the new college rising now above the level of the Grand Parade.

I earnestly recommend to your protection, the College now rising in this town. The state of the Province requires more extended means of education; and this College, open to all classes and denominations of Christians, will afford these means in the situation best suited to make them generally available. I am myself fully convinced that the advantages will be great even in our time, but growing, as it will grow, with the prosperity of the Province, no human foresight can imagine in what extent it may have spread its blessings, when your children’s children shall compare the state of Nova-Scotia to what it is now.[49]

There was more to this than encomiums and good wishes. Dr. John Inglis, minister of St. Paul’s Anglican Church, and in effect the coadjutor bishop in Bishop Stanser’s long absence in England, had been hard at work arousing the Church of England clergy, and anyone else who would listen, against a college at Halifax. Inglis was a King’s man; he was the first student to register there in 1788, and he had married Cochran’s daughter in 1802. He had always taken the position that in Nova Scotia one college was enough, and more than enough “for several centuries,” as he put it. In the light of the actual condition of King’s, he was even more fearful and resentful at the building of the “quite needless and romantic” college at Halifax.[50]

Lord Dalhousie had good reason to have the laying of the cornerstone of Halifax College done with every bit of ceremony, military and masonic, that the old town and his own energy and power could muster. On Monday, 22 May 1820 troops from the garrison formed a lane from the Granville Street side of Province House to the Parade and to the railed enclosure at the northern end. There was already formed a square manned by the Masons. In ceremonial procession from the Province House came Lord Dalhousie, the admiral, the chief justice and all the Council (except for Bishop Stanser) at a few minutes before two o’clock in the afternoon. There was a vast assemblage of people, among whom was a reporter from Royal Gazette, perhaps young John Howe, or his half-brother Joseph, then sixteen years of age. Before laying the cornerstone, Lord Dalhousie felt that he owed it to himself and to the college to tell those present:

I have never yet made any public declaration of the nature of the Institution I am here planting among you; – and, because I know that some part of the Public imagine, that it is intended to oppose the College already established at Windsor.

This “College of Halifax” is founded for the Instruction of youth in the higher Classics, and in all Philosophical Studies: – It is formed in imitation of the University of Edinburgh: – Its doors will be open to all who profess the Christian Religion; to the Youth of His Majesty’s North American Colonies, to strangers residing here, to Gentlemen of the Military as well as to the Learned Professions, to all in short who may be disposed to devote a small part of their time to study. It does not oppose the King’s College at Windsor, because it is well known that College does not admit any student unless they subscribe to the tests required by the Established Church of England and these tests exclude the great proportion of the Youth of this Province … it is founded on the principles of Religious Toleration secured to you by the Laws, … and if my name as Governor of the Province can be associated with your future well-being it is upon the foundation of this College that I could desire to rest it. From this College every blessing may flow over your Country: – in a few months hence, it may dispense blessings to you whom I now address; may it continue to dispense them to the latest ages! Let no jealousy disturb its peace, let no lukewarm indifference check its growth.

Protect it in its first years, and it will abundantly repay your care.[51]

The cornerstone was then laid. The grand master of the Masons gave Lord Dalhousie the corn, wine, and oil which were duly poured upon the newly laid stone. A royal salute was fired from the guns at Fort Charlotte, on George’s Island; this was followed by three times three cheers from the crowd. It was unforced enthusiasm; there it was, a Halifax College being started, and Lord Dalhousie himself was much liked.

Ten days later, Lord Dalhousie’s successor, Sir James Kempt, another middle-aged soldier from the Peninsular Wars, sailed up the harbour and took the oath of office. Lord Dalhousie’s tenure of Nova Scotia was at an end. His things were already packed on board HMS Newcastle, a Royal Navy frigate anchored off the dockyard, waiting to take him to Quebec. Kempt had been asked particularly to keep a fatherly eye on the new college building on the Parade and, honest soldier that he was, he would follow instructions. That care would be needed more than ever now that Lord Dalhousie was far away in Quebec City. For, among the cheers of the Halifax crowd at the laying of the cornerstone, Dalhousie could already discern the sound of the grinding of axes.

- The history of the Dalhousie Castle and the Ramsay family is contained in a pamphlet available at the Castle. It strikes one as accurate, but it is the only authority that I have for the Duke of Wellington’s remark about Lord Dalhousie at the Battle of Waterloo. See also Elizabeth Longford, Wellington: The Years of the Sword (London 1969), pp. 383-6; and Peter Burroughs, “George Ramsay,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vii: 712-33. ↵

- There is a brief but interesting description of this trip in a letter from Lord Dalhousie to the Duke of Buccleuch, 2 Dec. 1816, from Halifax in the Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol.2, Library and Archives Canada. The most accessible source for Dalhousie’s journals is Marjory Whitelaw, ed., The Dalhousie Journals ([Toronto] 1978). This is an edited version of an extensive journal that Lord Dalhousie kept from 1800 onward, which is in the Earl of Dalhousie Papers, in the Scottish Record Office, Edinburgh. These papers are extensive, and the British North American section of them has been microfilmed by Library and Archives Canada in fifteen reels. In 1938 the same organization published a catalogue with brief annotations of the letters. There are volumes of typed transcripts of these letters from the 1938 catalogue. ↵

- Brian Cuthbertson, The Old Attorney General, (Halifax [1980]), p. 70. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Sir John Sherbrooke, 15 June 1818, private, from Halifax, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 2, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Thomas Chandler Haliburton, The Clockmaker or The Sayings and Doings of Samuel Slick of Slickville, New Canadian Library edition (Toronto 1958), pp. 46-7. ↵

- The original watercolour is in the J. Ross Robertson Collection in the Toronto Central Library, and is the frontispiece in vol. 2 of T.C. Haliburton’s An Historical and Statistical Account of Nova-Scotia (Halifax 1829), published by Joseph Howe. For the Duke of Kent, see W.S. MacNutt, “Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent and Strathearn,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, V: 297-8; also Cecil Woodham-Smith, Queen Victoria: From her Birth to the Death of the Prince Consort (New York 1972), pp. 10-11. For the history of the Citadel, see John Joseph Greenough, The Halifax Citadel, 1826-60: A Narrative and Structural History, Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History, no. 17 (Ottawa 1977). ↵

- See Nova Scotia, Statutes at Large, 1817-1826 (Halifax 1827). The 1817 act on the Halifax Water Company is 57 Geo. III, cap. 15; that for the Halifax Watch is 58 Geo. III, cap. 13; the “Act to prevent disorderly Riding, and driving of Carriages” is 3 Geo. iv, cap. 23. ↵

- Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 11 Nov. 1816, pp. 21-2. Alexander Croke’s satire is called “The Inquisition,” and is in Nova Scotia Archives, MGX, 239c, reprinted in the Dalhousie Review 53, no. 3 (Autumn 1973), pp. 404-30. The quotation is from canto 4, lines 89-95. ↵

- See Thomas H. Raddall, Halifax: Warden of the North (Toronto 1948), pp. 108-9, for the raffish life led by garrison officers in Halifax. For drinking in rural Nova Scotia, see Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 10 Aug. 1817, p. 45. ↵

- Cuthbertson, Old Attorney General, pp. 76-7. ↵

- For the full story of this action see H.F. Pullen, The Shannon and the Chesapeake (Toronto 1970), pp. 52ff. ↵

- Peter Burroughs, “Sir John Coape Sherbrooke,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, v: 713. ↵

- Halifax currency was a system of reckoning colonial accounts, already established by 1820, that started in Nova Scotia and spread to the other British North American colonies. One pound Halifax currency equalled four dollars American. Thus a shilling was the same as twenty cents. The Newfoundland twenty-cent piece, still prevalent in 1949, was a remnant of this old system. One pound sterling equalled $4.86 American. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Sir John Sherbrooke, 17 Jan. 1817, from Halifax, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 2, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Archibald MacMechan, Late Harvest (Toronto 1934), pp. 49-50. It was composed as a song, to be sung to the tune of “The Laird of Cockpen.” MacMechan was professor of English at Dalhousie University from 1889 to 1931. ↵

- Lord Dalhousie put a summary of Sherbrooke’s suggestions before his council. See Nova Scotia, Executive Council, Minutes, 11 Dec. 1817, pp. 195-8, RG1, vol. 193, Nova Scotia Archives. Although the reference here is to the Executive Council, in fact the Council, as it was called, combined legislative and executive functions and there would have been no Executive Council as such. In 1838 when they were officially separated the designations Executive Council and Legislative Council begin. ↵

- “Daily Memoranda of Business,” Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 4, Library and Archives Canada. These are brief notes by Lord Dalhousie on what went on in council, and cover the years 1816 to 1820. See 31 Oct., and 6 Nov. 1816. ↵

- “Daily Memoranda of Business,” 20 Feb. 1817, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol.4, Library and Archives Canada. Lord Dalhousie noted that Council’s suggestions were so various that he set them down without approving any one of them. This clutch of important, long-serving, powerful, and sometimes greedy men can be best studied in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vi and vii. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Bathurst, 15 May 1817, Lord Dalhousie Papers, microfilm A525, Library and Archives Canada. These papers include an outgoing correspondence book in which despatches were copied. ↵

- Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 24 Sept. 1817, pp. 62-3. For a more benign and perhaps bowdlerized account of King’s at this time, see F.W. Vroom, King’s College: A Chronicle, 1789-1939; Collections and Recollections (Halifax 1941), pp. 50-2. For a general perspective on King’s within the setting of the Anglican Church establishment, see Judith Fingard, The Anglican Design in Loyalist Nova Scotia 1783-1816 (London 1972), especially pp. 152-4.The story of the docking of the Bishop’s horses comes from Thomas McCulloch, a dozen years later. See Letter from McCulloch to James Mitchell of Glasgow, 4 Sept. 1829, from Pictou, Thomas McCulloch Papers, vol. 553, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- For McCulloch, see the essay by Susan Buggey and Gwendolyn Davies in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, VII: 529-41, with a comprehensive bibliography. Marjory Whitelaw has published a useful booklet with the Nova Scotia Museum, Thomas McCulloch: His Life and Times (Halifax 1985). ↵

- From a letter to Edward Mortimer by Lord Dalhousie, 11 Mar. 1819, published in the Pictou Observer and Eastern Advertiser, 11 Sept. 1838. See also Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 10-15 Sept. 1817, pp. 53-8. ↵

- There is an extensive literature on the history of the Presbyterian Church. One of the best is J.A.S. Burleigh, A Church History of Scotland (London 1960). There is a useful chart at the back that shows the history of the splits and subsequent reunions in the Scottish church. ↵

- A good description of the Pictou County feuds is in W.L. Grant and F. Hamilton, Principal Grant (Toronto 1904), pp. 14-18. See also George Patterson, The History of Dalhousie College and University (Halifax 1887), p. 8. ↵

- Letter from McCulloch to James Mitchell of Glasgow, 6 Nov. 1834, from Pictou, Thomas McCulloch Papers, vol. 553, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- Letter from McCulloch to James Mitchell, 4 Sept. 1829, from Pictou, Thomas McCulloch Papers, vol. 553, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- Nova Scotia Archives, RGI, vol. 193, Nova Scotia, Executive Council, Minutes, 11 Dec. 1817, pp. 195-8, RG1, vol. 193, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- This despatch and the reply to it Lord Dalhousie presented to the legislature on 17 Feb. 1819, asking for support. The despatches appeared in print, however, only in 1836. See Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, Appendix 58, pp. 125-6. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Sherbrooke, 29 Dec. 1817; Letter from Sherbrooke to Dalhousie, 4 Feb. 1818, from Quebec, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 2, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Nova Scotia, Executive Council, Minutes, 6 June 1818, pp. 240-1; 18 Dec. 1818, p. 272, RG 1, vol. 193, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- See George Shepperson, “Andrew Brown,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vi: 87-9. ↵

- Both letters are in Lord Dalhousie Papers, microfilm A525, 20 May 1818, from Halifax. They are also in Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 31, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Almost any edition of Robert Burns will have “A Man’s a Man for a’ that” and “The Cottar’s Saturday Night.” The only point to be made here is that the last line, in quotation marks, is from Alexander Pope’s Essay on Man (1733). The previous line, “Princes and lords are but the breath of kings” is from Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Deserted Village,” put in more succinct form. Bums was well read in the English poets of his time. ↵

- Elie Halevy has a good short description of Scottish education in England in 1815. A History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century (New York 1949), pp. 540-1. ↵

- G.E. Davie, The Democratic Intellect: Scotland and her Universities in the Nineteenth Century (Edinburgh 1961), pp. 11-13. ↵

- Letter from George H. Baird and Andrew Brown to Earl of Dalhousie, 1 Aug. 1818, from the College, Edinburgh, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 31, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from George H. Baird to Lord Dalhousie, 4 Aug. 1818, from Edinburgh, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 3, Folder 12, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from A. Brown to Lord Dalhousie, 3 Aug. 1818, from Larkfield, near Edinburgh, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 2, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Nova Scotia, Executive Council, Minutes, 18 Dec. 1818, p. 272, RG 1, vol 193, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1819, 11 Feb. 1819, pp. 6-7. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1819, 14 Apr. 1819, p. 113. ↵

- See David Sutherland, “Michael Wallace,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vi: 798-801. ↵

- Minutes of the Trustees of the College, Halifax, 12 Mar. 1819, Board of Governors, Dalhousie University Archives. See also Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 12 May 1819, p. 110. ↵

- Three letters: from Trustees to Earl of Bathurst, 3 Dec. 1819; from Nathaniel Atcheson to Lord Dalhousie, 6 Jan. 1820, from London; from Bishop Robert Stanser to Lord Dalhousie, 8 Jan. 1820, from London; Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 31, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from Lord Dalhousie to Bathurst, 15 May 1820, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 31, Dalhousie University Archives. For King’s Royal Charter, see Vroom, King’s College, pp. 34-5; Fingard, Anglican Design, pp. 151-2. ↵

- Letter from Board of Trustees to Professor James H. Monk, 15 May 1820, Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 4, Folder 31, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from Lord Dalhousie to Bathurst, 20 May 1818, private, from Halifax, Lord Dalhousie Papers, A525, Library and Archives Canada; Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 2 Aug. 1819, p. 153. ↵

- Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 22 Nov. 1819, p. 173. ↵

- Nova Scotia, Assembly, Journals 1820, 3 Apr. 1820, p. 246. ↵

- Letter from Inglis to Kempt, 12 Sept. 1823, from Halifax, Lord of Dalhousie Papers, vol. 12, Library and Archives Canada; Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 23 May 1820, p. 195; Judith Fingard, “John Inglis,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vii: p. 433. ↵

- This speech was reported by the Royal Gazette, 24 May 1820 and reprinted in the Acadian Recorder, 27 May 1820. A partial version of it is in Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 23 May 1820, pp. 195-6. ↵