1 Dalhousie in the 1920s

The Board of Governors in the 1920s. George Campbell, G.F. Pearson, and President MacKenzie. Murray Macneill, Dalhousie’s registrar. The style and idiosyncrasies of Archibald MacMechan. Founding the Dalhousie Review. H.B. Atlee and Obstetrics. The Dental Faculty. Completing Shirreff Hall. The President’s house. The Dalhousie Student Council and the Gazette.

he charter of Dalhousie University in the 1920s was still the act of 1863, with an 1881 addition to comprehend the new Law Faculty and another in 1912 to bring in the Halifax Medical College and the Maritime Dental College. The Board of Governors consisted of twenty-three gentlemen and one lady, the alumnae representative, Dr. Eliza Ritchie. All were appointed by the lieutenant-governor-in-council (the provincial cabinet) on the nomination of the board. Close ties with the government made that process effortless. The board included George H. Murray (1861-1929), the premier since 1896. Most board members lived in or near Halifax; R.B. Bennett (’93) was one of the few not normally resident in Nova Scotia. He was MP in Calgary, leader of the opposition in the House of Commons after 1927 and from 1930 to 1935 the prime minister of Canada. W.S. Fielding, another important board member, was a Nova Scotian, former premier, but until 1925 mostly in Ottawa as Mackenzie King’s minister of finance. The board of that time was powerful and vigorous, representing both sides of politics, federal and provincial, and with many ties, personal and business, to the life and work of downtown Halifax. The board can be described as conservative. It could hardly be otherwise. Dalhousie University was paid for by student fees and endowments, and the only source of endowment came from rich men and women within and outside the province. Scrounging money was the board’s job and to some extent the president’s. So far, certainly since 1908 when George S. Campbell became chairman, Dalhousie’s board had made a fair fist of that.

Campbell was influential in persuading the Dalhousie board to take over the Halifax Medical College after the disaster of the Flexner Report. In 1909 Abraham Flexner, a classicist from Johns Hopkins, was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation to survey 147 medical schools in the United States and the eight in Canada. Flexner savaged most of them, and nearly half the American ones were forced to close down. The Halifax Medical College, distantly affiliated with Dalhousie, was not too well thought of either. But there had to be a medical school east of Montreal and in 1910 Dalhousie stepped in and the result was the creation of Dalhousie’s Medical Faculty in 1911. Campbell it was too who brought the board to buy the Studley estate early in 1911. Campbell had also done much to forge links between Dalhousie and the city. And his presence as such an active working chairman attracted others.[1]

The Dalhousie men who conceived and brought Studley into being liked and respected each other, especially the triumvirate of Campbell, G.F. Pearson, and President MacKenzie. Pearson took a Dalhousie LL.B. in 1900 and on the death of his father in 1912, succeeded him as the owner of the Halifax Morning Chronicle. As much as Campbell, Pearson brought Dalhousie into the Halifax business community. He used to stress the value of Dalhousie in plain business terms, likening it to a great enterprise with a capital of over $2. million, a plant estimated conservatively at $3 million, and contributing $1 million annually to the city’s business. As president of the Alumni Society he galvanized that sleepy organization into life. When the new buildings were going up at Studley during and after the war, Pearson watched them almost stone by stone. He seemed more often at Studley than he was at his desk at the Chronicle building on Granville Street. Pearson’s recognition of the desperate shortage of student accommodation in Halifax after the war brought the purchase of the Birchdale Hotel on the North-West Arm in June 1920.[2]

President Arthur Stanley MacKenzie (1865-1938) had been since 1911 the executive head of Dalhousie upon whose shoulders had fallen the weight of responsibility, correspondence, and supervision, together with the unending and thankless work for the federation movement. Much of the tone and character of the university, for good or ill, depended upon what sort of man the president was. Having been a widower since his wife’s death in 1897 (after barely more than a year of marriage), himself bringing up their infant daughter, MacKenzie’s life had a different centre to it than had other Dalhousie presidents. He never remarried, and there is not a scrap of evidence that he ever cared to. After he came as Munro professor of physics in 1905 MacKenzie established a powerful reputation; as a teacher he had a commanding presence and was a positive artist with chalk and blackboard. He was the first Dalhousie graduate to become its president, and from then on Dalhousie became the core of his life. Loyal, patient, far-sighted, generous, MacKenzie was a rare president, blessed with dignity and common sense, who seemed to be able to mix Scotch and fishing with his many Dalhousie responsibilities.

One illustration of MacKenzie’s style, his feeling for Dalhousie and her traditions, was his reply to Professor Archibald MacMechan who in 1923 wanted out of invigilating examinations. Most professors hated that chore, and MacMechan at age sixty-one felt he was entitled to look for an easing of that unrewarding burden. MacKenzie was both kind and firm, reading MacMechan a lesson in old Dalhousie democracy:

I was surprised and pained to receive your written complaint this morning about the work of invigilating. You have mentioned it to me verbally once or twice, and I took it in the only spirit in which it should be taken. Have you forgotten the good old adage “noblesse oblige”, which in this case might be read “vieillesse oblige”? I do not see how any distinction can be drawn between one member of the staff and another, unless decrepitude sets in, and have that democratic spirit retained through the whole faculty which is an essential of our Dalhousie mode of life. Personally, I hope the time will never come in my stay at Dalhousie when I shall feel superior to attending to the miserable, petty, time-consuming little details and jobs that come before me every day.[3]

Of course Dalhousie asked much of its professors. Some had to earn, some chose to earn, extra income. MacMechan worked many of his summers, teaching at Columbia, Harvard, or elsewhere, in the heat of big cities. In winter he wrote a weekly book column for the Montreal Standard, “The Dean’s Window.” Salaries were not unreasonable for the standards of the time, but after 1917 inflation made life more difficult on a fixed income.

Murray Macneill, Archibald MacMechan, and others

After the president, the most important university official was the registrar, Murray Macneill, professor of mathematics. He was a power in the university. Registrars had to be exigent to prevent the world, professors, and students, from making end runs around rules and regulations. Murray Macneill had come to Dalhousie in 1892 out of Pictou Academy at the age of fifteen, a brilliant student and still growing up. He graduated in 1896 at the age of nineteen with the Sir William Young medal in mathematics. He made a lasting impression on a number of people, not least Lucy Maud Montgomery who was at Dalhousie for a year in 1895-6. There is a Macneill family tradition that the character of Gilbert Blythe in Anne of Green Gables (published in 1908) was modelled after Murray Macneill. He was not enthusiastic about the alleged resemblance. He went on to do graduate work at Cornell, Harvard, and Paris. When Professor Charles Macdonald died in 1901 Macneill was a candidate to succeed him. But he was only twenty-three years old and the professorship went to Daniel Alexander Murray (’84), a PH.D. from Johns Hopkins. Macneill was too young then, but when the mathematics chair again became vacant in 1907, Macneill was appointed. He came back to Dalhousie from McGill and stayed for the next thirty-five years.[4]

He became Arts and Science registrar in 1908 and in 1920 registrar of the university. The same year he was given an associate to help him in teaching mathematics, while he took over the correspondence with students and getting out the calendar – for all of which he was given an additional $500 a year. It was a taxing job. He would see each student at registration, and would consider in the light of their matriculation marks, their own wishes, and Dalhousie’s rules what best they ought to do. More than one student found not only hopes for dodging hard courses thwarted, but ended up the better because Murray Macneill found some combination of classes that suited the student’s talents, knowledge, and experience. Frank Covert, who walked up to Dalhousie in 1924 at the age of sixteen, had reason to be grateful to Macneill not only as registrar but for his luminous teaching in mathematics. Covert said he was “one of the greatest teachers I’d ever known.” Macneill’s specialty was analytical geometry. John Fisher, not as able as Covert, entered a few years later; his matriculation marks in French and Latin were abominable and, heading for Commerce, he wanted to avoid Latin at all costs. Could he not take another language instead? Macneill’s massive head with the fuzzy fringe made a slow and deliberate negative sweep. “Well thanks, Mr. Macneill,” said young Fisher. Then he played a desperate card put into his hands only minutes before. Macneill was an avid and successful curler; Fisher asked if he could come and watch Macneill curl sometime. The registrar pricked up his ears. “Come and see me next week when I’m not so busy,” he said. Fisher duly came back, expecting to get out of taking Latin. It was not even mentioned; they discussed curling. Fisher never did escape Latin. Perhaps it was good for him. He reflected later, “After all, his [Macneill’s] first love was Dalhousie University. He had helped to guard her high standards.”[5]

The oldest of these guardians of standards in Arts and Science was Howard Murray, McLeod professor of classics since 1894, dean of the college since 1901. He was sixty-six in 1925, happy in his work, and would not hear of retirement. Murray was a careful, solid, and for some students too stolid, lecturer; but he was much in demand as after-dinner speaker, for he had wit, with mordant sarcasm and cryptic apothegms thrown in for savour. Once a year in Latin 2 he would relax and read slangy versions of Horace’s odes, including one that began, “Who was the guy I seen you with last night?” After one of those he would double up with laughter.[6]

Archibald MacMechan, Munro professor of English since 1889, was three years younger than Murray and quite a different character. He was often the first professor the first-year students encountered, for he did English 1 himself. There he would stand in the big Chemistry theatre, well-proportioned, elegantly dressed, with gown, handkerchief in his left sleeve, his squarish face made less so by a well-groomed, pointed beard. He expected his students to comport themselves as gentlemen and ladies. He much disapproved of chewing gum, and it was not tolerated in his classes. He also had a horror of sweaters, so much so that he would not even use the name, calling them, with disgust, “perspirers.” Any student who was misguided enough to wear a perspirer would be politely asked to leave the lecture.

MacMechan was proud of Dalhousie, proud of her traditions, proud of what he sometimes called “that pastry cook’s shop,” proud of his students. His lectures were not flashy; they were, rather, carefully crafted and they covered a great deal of ground. He commended Ruskin’s definition of poetry: “the suggestion, by the imagination, of noble grounds for the noble emotions. ” That says something, also, of MacMechan. He touched other literatures besides English; G.G. Sedgewick (’03) later professor of English at the University of British Columbia, first learned of Goethe’s magical “Kennst du das Land” and Beethoven’s music for it from Archie MacMechan.

MacMechan worked hard. He read and marked all of the twenty themes each student in English 1 had to write, until in 1922-3 he got an assistant, C.L. Bennet, a New Zealander, to help him. His comments he would put on the themes in red ink; beside something he particularly liked he would put a wavy red line, what he called “a wriggle of delight.” MacMechan’s own writing was like him, fastidious not forceful, full of grace and delicate elaborations. Yet he liked blood-and-thunder history and could render it, writing majestically of ships and the sea. And he could rise to occasions. He gave a speech to a football pep rally once, though it could not have had that name or Archie would never have come to it; he knew the game of rugby, although he was lame and could not play. He gathered the Dalhousians around him, and spoke. It was grave, quiet, almost solemn. One felt more in a chapel than in a pep rally. He made the Dalhousie students feel as if they were the privileged citizens of a great and wondrous city. “No one will ever persuade me,” wrote one of the students present, “that Archie did not turn the trick of victory (it was a near thing) on the next afternoon.”[7]

There were the younger men; Howard Bronson, Munro professor of physics who had come in 1910 out of Yale and McGill. A fine teacher with a knack for asking seriously inconvenient questions on examinations, he was becoming preoccupied now with the Student Christian Movement and was losing his grasp of research in physics. His younger rival was J.H.L. Johnstone, short, strong, and with a robust practical edge to his physics. George Wilson in history, and R. MacGregor Dawson, a political scientist who taught economics, roomed at 93 Coburg Road with Sidney Smith, the new lecturer in law. They were three young bachelors and could kick up a precious row now and then, like overgrown schoolboys. Dawson was from Bridgewater via the London School of Economics, and as Wilson once said was “noisy as hell and straight as a tree”; Dalhousie would not be able to hold him. George Wilson loved the place, admired MacKenzie, and had no urge to move. He migrated to Ontario each summer to the family farm in Perth or to the Ottawa Archives to finish off his Harvard PH.D. Sidney Smith it was, newly appointed in law, who chased Beatrice Smith, the eighteen-year-old secretary of Dean MacRae, down the hall of the Forrest Building on his bicycle. She escaped and the new lecturer ran into President MacKenzie instead. Dawson and Smith were Nova Scotians who ended in the University of Toronto; Wilson was an Ontarian who ended in Nova Scotia. All were unusually bright and vigorous teachers.[8]

H.L. Stewart and the Dalhousie Review

Among the Europeans at Dalhousie was H.L. Stewart (1882-1953), Munro professor of philosophy since 1913, hired from the University of Belfast. Writing was Stewart’s forte and he had a sharp eye for the contemporary scene. With good reason he was appointed the founding editor of Dalhousie’s first venture into academic publishing, the Dalhousie Review, which appeared in 1921.

The Dalhousie Review was a successor journal to the University Review which, before it faded after the war, had been a quarterly based on contributions from McGill, Queen’s, Toronto, and Dalhousie. The proposal to begin a literary and scientific quarterly at Dalhousie was discussed at MacKenzie’s house just before Christmas 1920, with the board executive, Dugald MacGillivray of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, Clarence Mackinnon, two other board members, and a group from the Dalhousie Senate – Dean MacRae, Archie MacMechan, Howard Murray, H.L. Stewart, together with Alumni and Alumnae representatives. The journal was announced to the three thousand or so Dalhousie alumni in March 1921, and promptly produced fifty subscribers. Despite that thin start, the Review Publishing Company was formed and the shares were taken by board members and alumni; thus its board of directors was a subset of the board itself.

The early years of the Dalhousie Review was a savoury feast, a deft blending of old and new, popular and academic, eminently readable. Stewart would run it for twenty-five years. He endeavoured, with some success, to render untrue a limerick he received in the mail in 1937:

There was a young man from Peru

Who’d a cure for insomnia, new,

Let the insomniac

Just lie on his back

And read the Dalhousie Review.

It was the first of the important university quarterlies – critical, independent, and crossing a wide spectrum of interests. H.L. Stewart’s work on it meant, however, that his attention to his philosophy classes was thinner than before. When he first came he was an able teacher; by the 1920s there were suspicions that he was easing up on the oars. That was the view of the registrar, Murray Macneill. In 1919 only one student registered for Philosophy 4. Dalhousie practice was to give a course even if there were only one student. The student withdrew; Macneill believed the student had been “persuaded,” although Stewart denied it. With good students Stewart was generous, inviting them to his house for tea and talk; but generally by the mid-1920s it was known privately that Dalhousie philosophy teaching was a far cry from the great days of Schurman, Seth, or Walter Murray. Stewart’s publications and research, his work of editing the Review, and by the 1930s his work in radio, would take their toll on his undergraduate lectures, upon which Dalhousie set such store.[9]

H.B. Atlee and Obstetrics

In 1922 a Dalhousie professor was hired who would become just as well-known as Stewart at publication and a good deal better at his lectures, a young gynaecologist and obstetrician, Harold Benge Atlee. He had graduated from the old Halifax Medical College in 1911 on the eve of its metamorphosis into the Dalhousie Medical Faculty. Atlee (1890-1978) was born in Pictou County, brought up in Annapolis Royal; he carried off school prizes, tied for a prize at medical graduation, and went overseas for postgraduate study after two years of private practice in rural Nova Scotia. He took up surgery, came to specialize in female surgery, and was in charge of that division at St. Mary’s Hospital, London, when the 1914 war broke out. He joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, served at Gallipoli, Salonika, and in Egypt, emerging a major with a Military Cross and twice mentioned in the despatches. He took his FRCS (Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons) in Edinburgh in 1920. He then sat down and wrote President MacKenzie.

It was not exactly a modest letter, but Atlee had never been modest. He said there were few Halifax doctors who had given more time to postgraduate study than he had. He was planning on returning to Halifax, and he hoped the president would keep him in mind should an opening develop at Dalhousie in Obstetrics and Diseases of Women. MacKenzie encouraged him, saying that Dalhousie was confidently expecting Rockefeller money to help finish the new maternity hospital. As Atlee doubtless knew already, the professor of obstetrics and gynaecology, Dr. M.A. Curry, performed no surgery at all, and was close to retirement. The Grace Maternity hospital would open soon. Part of the agreement between the Salvation Army and Dalhousie (with the Rockefeller Foundation as the benign and rich uncle in the background) was that there would be public beds in the Grace to which Dalhousie would have the nomination of medical staff. Five were duly nominated, active in obstetrics, one of them expecting to be named professor when Curry retired. None was. The reason was the Victoria General and Dalhousie had concluded that drastic action was needed to improve the teaching and clinical work in obstetrics and gynaecology. It meant the appointment of a new professor and a department that would combine the Obstetrics at the Grace and the Gynaecology at the Victoria General. In September 1922 the dean of medicine, Dr. John Stewart, and President MacKenzie recommended, as professor and chairman of the first combined Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, as chief of service at the Victoria General, the thirty-two-year-old Harold Benge Atlee.[10]

The appointment of Atlee created an almighty row. The obstetricians resented the young outsider. The surgeons at the hospital took the view that their level of competence required fifteen to twenty years of practical experience. Moreover, they had substantial gynaecological work; any appointment that aimed to separate them from their gynaecological surgery would be resented, indeed resisted. What made this one worse was that this young man, from out of town, seemed to think he could do it, and he would have control over such patients in the general wards. The Halifax Mail called the appointment “a quite extraordinary one.” At this stage Atlee was technically on leave, still working in specialist hospitals in London, where he was earning the highest praise from eminent surgeons. In Halifax the Hospital Commission met the outrage of the four surgeons most affected with the rejoinder that the recommendation for the appointment belonged to Dalhousie and Dalhousie alone, and it would not be undone. Nevertheless, President MacKenzie suggested to Atlee that he continue to work in England until June 1923 to let the furor cool down. That would take some time; on 12 April 1923 there was an evening’s debate about it, with criticism of the government, in the House of Assembly. Atlee, who was then at the Royal Chelsea Hospital for Women, took it all as free advertising, confident that by the time he returned to Halifax reports by senior colleagues in London would abundantly justify Dalhousie’s decision. “The impression we have all got,” wrote Dr. Comyns Berkeley, FRCS, senior surgeon at the Royal Chelsea Hospital, “is that Professor Atlee is a very able man, both in judgment, diagnosis, operative dexterity and the after care of patients… ”[11]

That and other recommendations from England stopped public criticism, as Atlee and MacKenzie believed they would. But it would take years before the bitter resentment of hospital colleagues would dissipate. Even the nursing staff were against him at first. One result was that he got very few specialist referrals in Halifax. It was not really until his own students were established in practice that Atlee received a sufficient number of referrals.

So he had to do something else: he wrote stories for the pulp magazines and for Maclean’s. One morning in the middle of his class, the professor of pathology came in to say that Atlee’s wife was on the telephone and had to speak to him. As he excused himself from class, Atlee wondered what new financial catastrophe was in store. What Margaret Atlee had to tell him was that the mail had just come and three of his stories had been sold! For a number of years Atlee would write a seven-to-eight-thousand-word story almost every weekend, some of them published under the nom de plume of Ian Hope. By 1928 he was earning more than $5,000 a year from magazines.[12]

Between 1922 and 1925 Atlee also wrote a weekly column in the Chronicle, “As I Was Saying,” under the initials P.D.L. Atlee was often outspoken and rough, the opposite of Archie MacMechan. There were hardly a dozen buildings in Halifax, he said, that were not architectural atrocities; not for Atlee the joy of the late nineteenth-century porches on Tower Road and South Park Street. He called those houses “clapboard monstrosities.” He was opinionated and he delighted in it. He would tell his students in obstetrics, via mimeographed notes (for he came to distrust student capacities for taking accurate notes), on symptoms of pregnancy, that as a rule their patients would be respectable married women; but it would “fall to your lot occasionally to be called upon by a venturesome virgin, or an incautious widow…” Atlee came to have opportunities to move elsewhere, but he never took them. He liked life where he was, feuds and all, architectural monstrosities or not. He eventually even lived in one, on South Park Street.[13]

Two years after Atlee’s arrival on staff, with the Grace Maternity Hospital going up, the Pathology Laboratory extended, the Medical Sciences Building completed, and the Public Health and Out-Patient Clinic at full service to the Halifax community, the council of the American Medical Association voted Dalhousie’s Medical School the coveted class “A” certificate. Dr. A.P. Colwell, the secretary, had visited Dalhousie in the summer of 1924, and now sent this happy news to MacKenzie, adding, “I know of no institution in which this higher rating is more richly deserved.” That was especially sweet to Dalhousie ears, for Colwell had helped Flexner do his 1910 survey of the old Halifax Medical College, and the devastating report that followed. The Dalhousie Gazette, the student paper, put out a special eight-page medical issue in November 1925 to celebrate the good news. The State Medical Boards of New York and Pennsylvania now gave recognition to Dalhousie Medical School degrees.[14]

The Faculty of Dentistry

Dalhousie’s newest faculty, Dentistry, had received outside recognition in 1922, ten years after it had been incorporated in Dalhousie. Nova Scotia had got its first Dental Act in 1891, and the Nova Scotia Dental Association was formed the same year. A board was established by which dentists were approved and registered. That did not mean they had degrees; in 1909 there were 114 dentists registered in Nova Scotia and nineteen of them had no degree at all. The other ninety-five had degrees, mostly from Philadelphia or Baltimore. The basis for the proper development of dentistry as a profession had to be a dental college in the Maritimes, and in 1907 a new Dental Act allowed the Dental Association of Nova Scotia to set up a College of Dentistry in Halifax. The following year Dalhousie Senate struck a committee to meet with Dr. Frank Woodbury, the dean of the Maritime Dental College, to establish an affiliated Faculty of Dentistry. It was an arrangement similar to the one Dalhousie had made with the Halifax Medical College: the Dental College gave the tuition and Dalhousie the degrees. Dalhousie also provided the Dental College with lecture rooms and clinical facilities tucked in at the southwest end of the main floor of the Forrest Building, where the library was, adjacent to where the present Dental Building now stands. The Maritime Dental College was owned and operated largely by the dentists themselves – a practitioners’ school, but better than most, for the dentists had been conscientious in designing its program. In 1911-12 there were seventeen students in the college; eight were in the first year of a four-year program, for which entrance was the same matriculation standards as the Faculty of Arts and Science.[15]

The Flexner Report, which forced the Halifax Medical College into abandoning its name and becoming Dalhousie’s Faculty of Medicine, had consequences for the Maritime Dental College as well. In 1912 Dalhousie took it over as it had taken over the Medical College. Thus the first class to register in the newly created Maritime Dental College in 1908 graduated in 1912 as Dalhousie’s first class in the Faculty of Dentistry.

The moving spirit behind this rapid development, as rapid it was between 1891 and 1912, was Dr. Frank Woodbury. He was born near Middleton in 1853, graduated from Mount Allison, and took his dentistry degree at Philadelphia in 1878. He eventually established a practice with his brother in Halifax. His great work was the incorporation of the Maritime Dental College into Dalhousie’s Faculty of Dentistry in 1912. Woodbury was one of those selfless men, sometimes from a Methodist background, with an uncompromising devotion to civil, provincial, and national work. Dean of the old Maritime Dental College, he became dean of the Dalhousie Faculty of Dentistry and it was Woodbury, as much as anyone, who helped to give Dalhousie Dentistry its standing. At the end of January 1922 Dr. W.J. Gies and four colleagues from the Carnegie Foundation (and the American Dental Association) visited Dalhousie’s Faculty of Dentistry and gave it a glowing report. All that was inhibiting further development was financial need. Shortly after the assessment team departed, Dean Woodbury died suddenly of heart failure. It was a sad blow, for there was almost no one among the volunteer dentists whom MacKenzie could fall back on. His successor was Dr. F.W. Ryan and after Ryan’s death two years later, Dr. D.K. Thomson, who would be dean until 1935.[16]

Curriculum and Students of the 1920s

The Dalhousie of the 1920s was crowded by all previous standards. In 1922 it had the largest enrolment so far, 753 students, of whom 60 per cent were in arts and science, the remainder divided between medicine, law, and dentistry. Women students comprehended 36 per cent of the arts and science programs as against 23 per cent in 1902. Some 45 per cent of arts and science students now came from Halifax, up substantially from twenty years before when only 30 per cent did. Overall, 35 per cent of Dalhousie’s students were Haligonians. Noticeable shifts occurred in regional representation. Pictou County, which in 1902-3 contributed 13.5 per cent of Dalhousie’s students, now gave only 8 per cent; Colchester County’s representation halved, as did Prince Edward Island’s; Cape Breton doubled.[17]

Admission to Dalhousie was by matriculation, sometimes called junior; students deficient in some subjects could make them up. In that case they were allowed to take only four classes in the first year. If they were weak in Latin or French, often the case with those whose matriculation was deficient, they were allowed to take only three classes. If students failed more than four classes at Christmas, they had to withdraw from Dalhousie, for at least a year. Class attendance of 90 per cent was required, and records were kept.

The big classes were in those old Dalhousie fundamentals, classics and mathematics, though modern languages were now required along with the classical ones. In effect some of the old mathematical core had been shifted over to modern languages. The twenty classes for the BA were the following:

- 2 classes in Latin or in Greek

- 2 classes in French, German, or Spanish

- 2 classes in English

- History 1

- Philosophy 1

- Mathematics 1

- 1 Science: physics, chemistry, biology, or geology

- 1 3rd-year language class, or Economics 1, or Government 1

- 8 other classes chosen so that at least four classes must be in one subject, and three classes in each of two others.

In 1922-3 some 220 students took Latin at various levels, divided roughly evenly between elementary Latin (an important make-up class) and Latin 1 and 2. Some 208 took French, mainly in French 1 and 2. There were 342 students in various levels of English, nearly half of those in the first year. First-year physics, history, and economics had about one hundred students each, chemistry’s first year had 141 students, with biology not far behind with 129.

The classes in the first year were each three hours a week with science classes requiring an additional two- or three-hour laboratory per week. Elementary Latin was offered to students whose Latin was rocky or non-existent, every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday at 11 AM with a fourth hour added after the class was formed and timetables worked out. Latin 1 required Cicero’s Oration against Cataline, Virgil’s Aeneid Book VI, and exercises in sight translation. Latin 2 went on to Livy and Horace.

There was talk in Senate of changing the attendance rule from 90 to 100 per cent. One-third of the students met on 5 November 1922 to protest such a change, and the proposal was withdrawn. At Christmas 1922 another rule came into question. Fourteen arts and science students, having failed more than four subjects, were asked to leave. It got into the local papers, and the press thought it too severe. President MacKenzie reported to Senate that the fourteen were in three groups: five students were “hopeless. They were idlers who took no interest in their work and showed no likelihood of possible improvement.” The second group “did not lack the diligence, but could not stand up to the work because of inferior ability.” A third group pleaded extenuating circumstances. The Senate decided that the first group would still be asked to leave Dalhousie, while the remaining nine were put on probation for four weeks.[18]

That occasioned some student comment. Was it true, the Gazette asked, that “Idlers, Drones, Social Climbers” were being ruthlessly weeded out? Who ought to be? Max MacOdrum (’23) took this up. A few months before, the president of Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, had raised similar questions, and came up with fairly stern answers. University was not a place, said President Hopkins, for “dainty idling, social climbing.” The only way to preserve Dartmouth College standards was to eliminate the deadwood. An “aristocracy of brains” existed, and the duty of the university was to discover it. Max MacOdrum’s answer did not question those assumptions so much as to ask what was the best means to eliminate deadwood. He was not at all sure that written examinations for first-year students were a good test. Two weeks later the Gazette offered the aphorism, reminiscent of old Charlie Macdonald’s 1892 address, that “following lines of least resistance makes rivers and men crooked.” With all the physical changes of the 1920s, so obvious to students, President MacKenzie reminded them that the university “is the same old Dalhousie, with the same old Scottish ideals of the steep, lonely path of learning. You go out from its halls with the feeling that you have earned what you have won.”

The first day of lectures of the session of 1922-3 was on Wednesday, 4 October. The length of the university year was cause for an extended debate in Senate that took up most of that autumn. The Canadian average was twenty-six weeks, shorter by several weeks than in the United States. The committee making recommendations wanted twenty-nine weeks, but it was divided and its divisions reappeared in Senate. President MacKenzie wanted the twenty-nine weeks, the length of the medical and dental years, conditions for those being quasi-statutory. Since arts and science classes ended three weeks earlier, conditions in some classes became, as MacKenzie put it, “demoralized.” At the end of a wrenching debate, medicine and dentistry continued with their twenty-nine week sessions, law was extended to thirty weeks, and Senate approved the idea of lengthening the arts and science session, though it could not yet say by how much. By the autumn of 1923 all that happened was that arts and science began on the first Monday instead of the first Wednesday in October.[19]

In January 1923 once more Senate tackled the lively issue of student dances. Students could not seem to get enough of them: Senate thought they were taking up entirely too much time and energy not only of the students but of Senate, which had to debate permissions to hold them. A dance policy was duly laid down: there would be a dance officer of Senate; Dalhousie dances were to be on Dalhousie premises; only students would be allowed to go (unless otherwise authorized); dances would end at midnight except the dance at Convocation which was allowed the luxury of 12:30; they could be on any day but Sunday; there were to be seven in all, three in the autumn, three in the spring, and the Convocation Ball. At each dance two members of staff had to be present. Smoking at dances was allowed but only in special rooms. Women students were not allowed to smoke.[20]

An advertisement in the Gazette for Rex cigarettes was social comment. The cigarette was consolation; a man in white tie and tails – Dalhousie dances were formal and tails were de rigueur – was sitting out a dance by himself, reflecting that the dance may be a bore, “the lady of one’s choice may be dancing with another – and yet there’s still a morsel of satisfaction in the dreariest of festivities for the man who says, NEVER MIND – SMOKE A REX!”

The Gazette‘s joke column, both original jokes and those culled from other university papers, illustrated something of the 1920s too:

Ray – Let’s kiss and make up.

May – Well, if you are careful I won’t have to.

That was the first Gazette of the 1922-3 session. Also announced was the first Freshie-Soph debate, for Thursday evening, 19 October: “Resolved that a Dirty, Good-Natured Wife is Better than a Clean, Bad-Humoured One.” Freshmen were to argue the negative, in favour of cleanliness and querulousness. It was a decidedly male theme. Jokes allowed other perspectives, including delightful ambivalence:

“What shall we do?” she asked, bored to the verge of tears.

“Whatever you wish,” he replied gallantly.

“If you do, I’ll scream,” she said coyly…[21]

Shirreff Hall and its World

Jennie Shirreff Eddy’s ambitions, and Frank Darling’s translation of them into architecture, aimed rather higher than all that. Dalhousie’s women students were to be introduced in Shirreff Hall to a social ambience in keeping with Dalhousie’s intellectual ambitions. Shirreff Hall opened in the autumn of 1923 under its new warden, Margaret Lowe, the former national secretary of the Student Christian Movement in Toronto. She was paid $1,500 a year with her room and board, and she would remain warden until 1930. Shirreff Hall was a special world and was so intended. It was to foster in young women modes of civilized living that not all of them had had opportunity to develop yet. Indeed, Shirreff Hall struck one girl, Florence MacKinnon of Sydney, as being too rich for her blood, that unless she were to marry a millionaire, she did not anticipate living in a millionaire’s house seven months of the year. Mrs. Eddy aimed to provide a home life that would have the effect, as she put it, of “rounding out the university’s training.” Frank Darling of Toronto was greatly intrigued with Shirreff Hall – it was his last major work – and thus Mrs. Eddy’s and President MacKenzie’s concerns, and Darling’s ingenuity at translating them, showed. And still does.[22]

The Morning Chronicle of 3 October 1923 praised it as a building of imposing beauty, inside and out. The stone was MacKenzie’s discovery. The local Halifax stone, ironstone, a metamorphosed slate, had been creating problems, mostly because it was so hard that mortar did not properly bond to it. The Macdonald Library and the Science Building had both revealed such problems, though none as bad as the new Anglican Cathedral was currently demonstrating. MacKenzie found a pinkish quartzite from New Minas, used successfully at Acadia. At Shirreff Hall it was mixed with triprock of a greenish hue. He was also particular about the slate for the roofs; that of the other Dalhousie buildings had been a sea-green slate from the north of England.

The interior fittings were done with love and attention, not least by a much travelled R.B. Bennett who found the firm in Minneapolis that manufactured doors that Bennett had seen and liked. A few months later, on his way to England, Bennett sent MacKenzie note-paper with the Shirreff crest. It was a rearing horse holding an olive branch, the motto being the well-tried, “Esse Quam Videri” (To be rather than to seem). That was for the china Bennett was proposing to order for Shirreff Hall in England.[23]

Shirreff Hall pleased nearly everyone. “I have never known,” MacKenzie told Bennett, “any building receive greater admiration and praise… I never look at it but I think how entirely pleased Mrs. Eddy would have been.” She had died in August 1911, and Frank Darling never lived to see the opening of Shirreff Hall; he died in May 1923. MacKenzie expected sixty-five girls for Shirreff Hall; there were, however, far more applicants than spaces, and that first year, 1923-4, there were eighty-five girls in Shirreff Hall, every corner occupied.

Fire drill in a late evening in March 1924 created a special stir. Fire captains found it hard to convince early sleepers that it was not morning although thoughts of breakfast stirred some. It brought forth some interesting specimens; as the Gazette’s Shirreff Hall reporter observed, one young lady “in curl-papers whose short jacket over a draped dressing gown was charmingly set off by a pair of rubber boots.” One student was missing from the roll-call, and Miss Margaret Lowe was much worried that had there been a real fire, the young woman would have been burned. But Miss Lowe’s fears were “calmed by the assurance that in the event she [the student] would only have boiled.”[24]

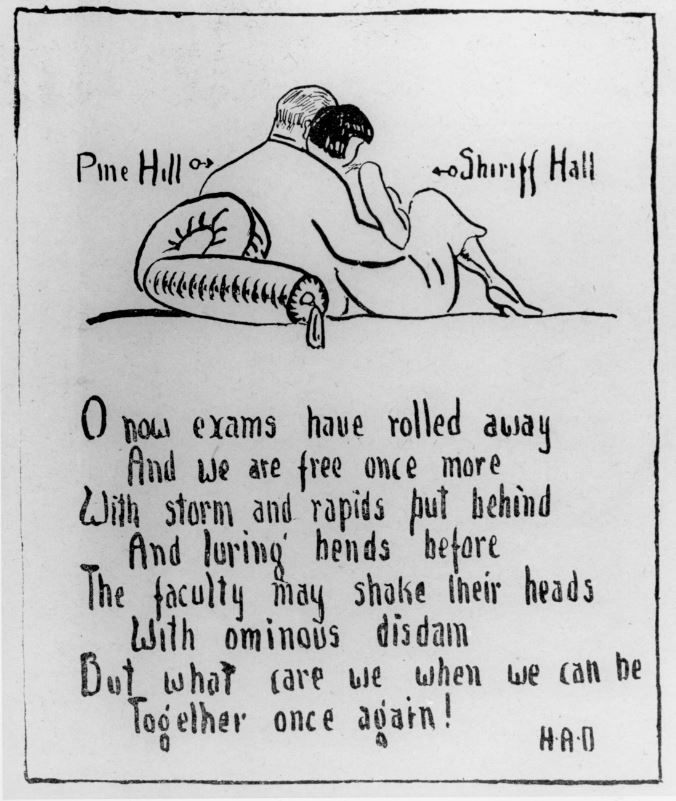

The long love affair between Shirreff Hall and Pine Hill now got under way. Pine Hill was the Presbyterian Divinity College on a lovely site on the North-West Arm, built in 1899. Pine Hill became United Church in 1926 and there were often more rooms than theological students to fill them. Dalhousie had never had male residences; the Birchdale Hotel that Campbell and Pearson had bought in 1920 for that purpose Dalhousie had had (reluctantly) to lease to King’s in 1923, pending completion of King’s own buildings in 1930. Thus Dalhousie male students lived everywhere in Halifax, although the university kept track of them and, from time to time, of the condition of the houses they lived in. Dalhousie men had always liked to board at Pine Hill when they could, just a half a mile’s pretty walk from Dalhousie (and Shirreff Hall in 1923). The Gazette noted it in January 1925, with a sprightly cartoon of Pine Hill, his arm around Shirreff Hall, she with her bobbed hair and silk stockings (with seam),

At Shirreff Hall bobbed hair was by that time very much in fashion: “the army of the unbobbed diminishes daily. Sometimes the shorn lambs do not much resemble their former selves.”[25]

A House for the President

R.B. Bennett, who had been mainly instrumental in bringing Mrs. Eddy and Dalhousie’s need for a women’s residence together, also effected the change of the president’s home from 14 Hollis Street. It was MacKenzie’s own house, bought before the new railway station at Cornwallis Square had been built, but handy to welcome presidents who came by train for federation meetings. Its access to Dalhousie was not so convenient. In 1924 G.S. Campbell was in the West on bank business but also looking at university buildings at Saskatoon, Edmonton, and Vancouver. Some of them made his mouth water, he said, “but for style, appropriateness, Dalhousie need not take second place to any of them.” In Calgary he met H.A. Allison, a partner in Bennett’s law firm, who asked advice about selling the property of his late brother, E.P. Allison, at 24 Oxford Street in Halifax. Campbell said Dalhousie would have loved to buy it but didn’t have the money. Bennett and Campbell met in London, England, in May 1925 and Campbell raised the question. Bennett had already left a substantial gift for Dalhousie in his will, but seized the opportunity to do something here and now. Early in June 1925 he telegraphed Campbell asking him to find the lowest price for which the Allison property could be bought. By that time the field behind it had been sold to a speculator, but there was still the big house and its grounds, 214 feet along Oxford Street and 326 feet deep, in all an acre and a half. Assessed at $14,000, it was bought by Dalhousie for $20,000, assessments being old and prices new. Bennett promptly donated the money. “I am really gratified,” he said, “to send this gift to the university to which I owe so much.” Campbell wired MacKenzie in Ottawa the good news. “Bennett donates twenty thousand to buy Allison house[.] prepare for an elaborate and juicy house warming.” Dalhousie spent another $8,000 fixing up the Allison house, and MacKenzie moved into it, as his official residence, late in 1925, with his daughter and her husband.[26]

Campbell convened an informal meeting at his house on 9 September 1926 to consider ways of developing better relations between students, staff, and alumni. Dalhousie’s big student body in the 1920s developed momentum of its own; the familiar staff-student relations of old did not seem to work as well. Since 1919 Dalhousie’s administration, especially President MacKenzie, had been heavily preoccupied with building and with university federation. Campbell’s informal meeting was the origin of the Committee of Nine – three students, three members of Senate, and three alumni – struck to work out relations between the students and Senate.[27]

Dalhousie Student Council and the Gazette

The Dalhousie Student Council had been established in its 1920s form in 1912, and for eight or nine years had worked well, dealing with student discipline and the administration of funds for student clubs. But beginning about 1920, and especially by 1925-6, the system began to break down on both those functions. Dean Howard Murray thought the Student Council had gradually abdicated its responsibility for student discipline, that its attitude appeared to be “that the Council’s function was neither to maintain order itself nor to assist the Senate in maintaining it, but to be oblivious of all infractions of discipline; that members of Senate must do the detective work, and that, when students are to be disciplined, the Council should interfere as far as possible to secure mitigation of the punishment.” L.W. Fraser, for the Student Council, explained to Senate that accusations about slack administration of student finances, particularly the lack of audit of club moneys, was true. As to discipline, students differed. Many of them felt they did not have a sufficient voice in establishing the rules. President MacKenzie noted that the Student Council had approved the original rules of 1912, and subsequent changes were made in consultation between the council and Senate. The Council of Nine may not have had, as the Gazette suggested, “plenary power to regulate University affairs” but it was an important body where the students could ventilate grievances. The Dalhousie Gazette was fairly blunt:

In the past the relation of the student towards the university has been, no matter how loyal, servile. He has had consciously or unconsciously a fear of the university administrators, because the latter have in their hands all authority… Take for example the shameless way university authorities use that old gag: “Remember that your presence at the university costs society every year so many hundreds of dollars. It is up to you to justify the investment.” No student has ever felt free to say to the university authorities: “Remember that society has entrusted to you – in addition to millions of dollars – the lives of its most promising youth. If you betray that trust, society is undone.”

Students had several complaints. One was against professors who kept their classes after the first bell and thus forced students to be late for one immediately afterwards, at which they would usually be marked as absent. Students objected to the library closing at 4:30 PM and in March 1926 a number petitioned for a closing time of 6 PM. They got 5 PM, and returned to the issue in November 1926:

The University Library is like a sponge of vinegar to a thirsty man. The books are not available. The Library opens at nine o’clock in the morning and closes at five in the afternoon. On Saturdays it closes at one o’clock; on Sundays it is not open at all… The stacks should be open to the student. Though hide and seek is all right in its place, there seems no reason why we should play this game with the university books… Wake up, University Authorities! Dalhousie has given you for the time being the job of running the university; we will not put up with any nonsense.

It was probably these last two sentences that occasioned a message for the editor, Andrew Hebb, to talk to the chairman of the board, G.S. Campbell. They met at the Halifax Club. Hebb apologized to Campbell and to the board in an editorial, and the library was opened in the evenings from 7:30 to 10 PM, beginning Monday, 6 December – an experiment on which future library hours would depend.[28]

In general the Gazette’s relations with the university were rarely so brusque. Andrew Hebb (’25, ’28) had been sub-editor the previous year when his brother Donald (’25), then at Truro Normal School, roused the ire of the principal, David Soloan (’88), by praising short skirts. Soloan complained to Hebb, who replied that the principal needed special glasses that would prevent him from seeing the lower half of any woman he met! That was not well received in Truro, and the issue ended up on President MacKenzie’s desk. MacKenzie was patient and sensible to Soloan’s protests. He was sorry the Gazette went in for that sort of thing, but it was the students’ paper and the Senate did not control it. Dalhousie did not interfere with the editors unless they did something

which is subversive of discipline or print anything which is disgraceful or discreditable, or directly runs counter to the best interests and good name of the University. Outside of that we find experience of a couple of generations has proved that it is much wiser to leave the students fairly free in their carrying on of their paper. This gives them a chance to blow off steam, and we have found that, with this spirit of arrangement between us, they seldom over-step the bounds set for them.[29]

Hebb probably knew nothing of this defence, but when he became editor in 1926 there was a definite effort to improve the Gazette’s style and vigour, to make it more a student newspaper and less a student literary magazine. There were newspaper connections as well; one sub-editor, a dental student, had worked for the Sydney Post, another on the Saint John Telegraph-Journal. Hebb’s adventures with Campbell in November 1926 did not prevent him some two months later from ascribing the large number of failures at the Christmas exams as faults, not only of students, but of professors. Students were usually aware of their weaknesses; professors were not, and they failed students right and left, not always being aware of their own failings as teachers. And there was sage advice in the Gazette in January of 1927. Dalhousie and Halifax were starting in on “the gray days” of winter, and even if they were monotonous as weather – there had been very little snow – they should not be allowed to drift by:

…for all that, the gray days have a charm, which is entirely lacking in those earlier, more interesting ones. There is practically nothing worthwhile doing in them but working and thinking… Let us try and get the most of these gray days. They are solid gray rocks, on which foundations may be built.

They were also occasional literary touches, one of them a poetic echo of gray days:

I love quiet things

Grey birds on grey wings

Night with the wind still

And grey fog upon the hill,

Rolling mist along the shore,

Lamplight through the open door

I love quiet things

Grey birds on grey wings.[30]

A New Chairman of the Board and Dalhousie’s Finances

George Campbell’s opening the library in the evening was one of his last contributions to Dalhousie. He had been ill in April 1927 but the doctors were hopeful he had recovered. In Montreal on business, he died suddenly of a heart attack on 21 November at the age of seventy-six, still president of the Bank of Nova Scotia, still chairman of the Dalhousie board. His greatest gift to Dalhousie had been his twenty years as its chairman. As President MacKenzie said, “Steadily, if slowly, he brought his colleagues… to see that his dreams were practicable… [As to his purchase of Studley], the effect was almost electrical.” MacKenzie’s and Campbell’s personal relations across those twenty years had been unusually harmonious and fruitful. For the loss of the strength, the mettle, of George Campbell there was no easy substitute.[31]

Nevertheless, his successor; Fred Pearson, had vigour of mind and fecundity of ideas. If he was more volatile than Campbell, he had tremendous energy and enthusiasm, which he gave readily to Dalhousie. It was Fred Pearson who had led the greatly successful Million Dollar Campaign of 1920, which had earned $2 million.

MacKenzie had told the board in 1922 that Dalhousie needed new endowment; by 1928 Dalhousie’s needs and ambitions had grown. Early in October 1929 MacKenzie urged the board to consider a new campaign for 1930-1. Dalhousie needed $5 million, but he anticipated $2 million in bequests over the next few years, and a campaign could aim at $3 million. MacKenzie and Pearson between them decided that they needed technical assistance, and they consulted John Price Jones, Inc., an American firm that specialized in university campaigns. It had recently delivered satisfactory results to Ohio State, Wellesley, Harvard, and Temple.

By American standards, Dalhousie was not well geared for an extensive campaign. The questionnaire prepared by John Price Jones asked, among many questions, “How many staff in the alumni office?” Dalhousie’s answer, “There is no staff in the alumni office.” Asked about an alumni secretary, Dalhousie replied there was none, nor had there ever been one. The last Alumni Directory was fairly recent, published in 1925, and a card catalogue of alumni had been a legacy from that. Dalhousie did have active alumni associations in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, and New York as well as in Halifax. On this basis the American firm prepared an organizational plan of campaign. This initial assessment cost $3,000, but the campaign was estimated to cost $100,000. If the campaign realized $3 million the cost would amount to only 3.3 per cent.[32]

Dalhousie’s current balance sheet for 1928-9 was as follows: income, $257,753; expenses, $254,953. Of its income, tuition fees represented 49 per cent, investments 36 per cent. Its expenditure broke down as follows: professors’ salaries, 59 per cent; building and maintenance, 18 per cent; administration expenses, 14 per cent; laboratories, 5 per cent; and libraries, 5 per cent.

Dalhousie’s total endowment had grown from $650,000 in 1919 to over $2 million in 1929. It was a portfolio not ill designed to absorb some of the shocks of the stock market crash of October 1929. Its investments were highly conservative, exemplified by cautious investments in stocks. Only 24 per cent of Dalhousie’s portfolio was in common stocks, two-thirds of which were bank stocks (mostly Bank of Nova Scotia), the rest in railways and utilities. The great staple of Dalhousie’s portfolio was bonds, some 62 per cent, of which almost two-thirds were in government bonds (mostly Dominion of Canada), and the rest in industrial bonds and trust debentures. By 1930 only 7 per cent of Dalhousie’s portfolio was in mortgages. The average rate of return across the whole of Dalhousie’s portfolio, as of 30 June 1930, was 5.68 per cent.[33]

But the effect of the October 1929 crash and the world financial crisis that followed meant that hopes for a great 1930 Dalhousie campaign that would exceed the 1920 one had to be reluctantly given up. Nevertheless, Pearson moved into the chairmanship with some confidence, demonstrated in his handling of the Gowanloch affair early in 1930, and Dalhousie’s change of presidents a year later.

- For the Flexner Report and its effects, see P.B. Waite, The Lives of Dalhousie University, Volume One, 1818-1925: Lord Dalhousie’s College (Montreal and Kingston 1994), pp. 202-4 (cited hereafter as Lives of Dalhousie 1). ↵

- G.F. Pearson (1877-1938) graduated from Dalhousie in 1900. He was twice married, to Ethel Miller in 1900 and after her death to Agnes Crawford in 1913. See Alvin F. MacDonald, “In Memoriam,” Dalhousie Alumni News, Nov. 1938. ↵

- There is a curious story about Mackenzie’s widowerhood that ought to be recorded. When his wife was dying she is reported to have said to him as prophecy, “You will never marry again.” This comes from Murray Macneill via his daughter, Janet Macneill Piers ('43). Interview with Janet Macneill Piers, Chester, NS, 17 Sept. 1992, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 3, Folder 49, Dalhousie University Archives. For two retrospective views of MacKenzie, see Alumni News, Nov. 1938, J.H.L. Johnstone, “MacKenzie - the Teacher,” and G.H. Anderson, “MacKenzie - the Scientist.” MacKenzie’s chiding of MacMechan is in letter from A.S. MacKenzie to MacMechan, 19 Dec. 1923, President's Office Fonds, “Archibald MacMechan,” UA-3, Box 96, Folder 25, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- MacMechan once described Macneill as “that Ferocious Registrar,” letter from MacMechan to A.S. MacKenzie, 9 July 1919, from Windsor NS, President's Office Fonds, UA-3, Box 96, Folder 25, Dalhousie University Archives. In the Macneill family papers there is a letter from Lucy Maud Montgomery in 1908 explaining how she has just begun work on the successor to Anne of Green Gables, interview with Janet Macneill Piers, 17 Sept. 1992, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 3, Folder 49, Dalhousie University Archives. Macneill’s account of his life at the Sorbonne in Paris is in Dalhousie Gazette, 3 Mar. 1899. ↵

- For Covert on Macneill, see Harry Bruce, “The lion in summer remembers Dal,” Dalhousie Alumni Magazine 1, no. 1 (Fall 1984), p. 15; for John Fisher, transcript of his CBC broadcast of 11 Mar. 1951, President's Office Fonds, “Murray Macneill,” UA-3, Box 98, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 9 Oct. 1930, letter by T.A. Goudge ('31) on Howard Murray; see also President's Office Fonds, “Howard Murray,” UA-3, Box 98, Folder 15, Dalhousie University Archives; letter from Andrew C. Hebb ('25, '28) to Peter B. Waite, 14 Dec. 1990, from Toronto. Mr. Hebb’s reminiscences are of unusual interest since he was editor of the Dalhousie Gazette from 1926 to 1927. ↵

- On Archie MacMechan the best essay is by G.G. Sedgewick ('03), “A.M.” in Dalhousie Review XIII, no. 4 (1933-4), pp. 451-8; also letter from Andrew C. Hebb to Peter B. Waite, 14 Dec. 1990, from Toronto; Eileen Burns ('22, ’24) gave me the story of “perspirers,” interview with Eileen Burns, 20 Aug. 1990, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 2, Folder 62, Dalhousie University Archives; MacMechan’s views are also noted in the Dalhousie Gazette, 22 Feb. 1916. ↵

- George Wilson gave me the description of Dawson, and also the story of Sidney Smith and the bicycle, the latter confirmed in interview with Beatrice R.E. Smith, 31 May 1988, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 3, Folder 64, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from D. Macgillivray to A.S. MacKenzie, 23 Dec. 1920; memorandum of same date; circular, Howard Murray to Dalhousie alumni and alumnae, 24 Mar. 1921, President’s Office Fonds, “Dalhousie Review, 1920-1933,” UA-3, Dalhousie Univeristy Archives. The original incorporators of the Review were Macgillivray, Pearson, I.C. Stewart, and J.S. Roper. Capital was $5,000 with two hundred shares. Fifty shares were held by the board, others were bought slowly over the next decade by governors, alumni, and professors, and in due course ended in estates. The first print run of 1921 was 7,100 but that was too ambitious; in the 1920s subscribers averaged 2,500. This information is in the R.B. Bennett Papers in the University of New Brunswick Archives, “History of the Dalhousie Review,” dated 27 Feb. 1936. The limerick comes from Henry D. Hicks to whom Stewart told it, interview with Henry D. Hicks, 8 July 1988, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 4, Folder 6, Dalhousie University Archives. Of Stewart’s carelessness with lectures the stories are legion. The 1919 incident is in a letter from H.L. Stewart to A.S. MacKenzie, 4 Oct. [1919], President’s Office Fonds, “Philosophy 1915-1955,” UA-3, Box 289, Folder 7, Dalhousie University Archives. There was another incident in 1921 about his being late for classes, about which Stewart wrote President MacKenzie, “The eagerness of the [Registrar’s] Office to report - or invent - charges of negligence on my part is not new to me.” Letter from H.L. Stewart to A.S. MacKenzie, 19 Oct. 1919, UA-3, Box 289, Folder 7, Dalhousie University Archives. George Wilson, dean of arts and science 1945-55, used to say that students in Stewart’s philosophy classes claimed they could use the notes made by their mothers or fathers, jokes and all. ↵

- Letter from Atlee to A.S. MacKenzie, 11 Apr. 1920, President's Office Fonds, “H.B. Atlee,” UA-3, Box 87, Folder 10, Dalhousie University Archives. See Harry Oxorn, H.B. Atlee, M.D. (Hantsport 1983), pp. 11-36. This biography has been criticized as unfair to Atlee by a fine Dalhousie surgeon; interview with Dr. Edwin Ross, 19 June 1989, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 3, Folder 53, Dalhousie University Archives. It is at time brutally frank, that can indeed be said. Whether the result is a balanced portrait is an open question. It is badly proofread and has no index, but vigorous it certainly is. ↵

- Halifax Mail, 26 Sept. 1922; letter from Atlee to A.S. MacKenzie, 11 Oct. 1922; letter from A.S. MacKenzie to Atlee, 7 Nov. 1922; letter from Dr. Comyns Berkeley to A.S. MacKenzie, 27 June 1923, Presdient's Office Fonds, UA-3, Box 87, Folder 10, Dalhousie University Archives; Halifax Herald, 13 Apr. 1923. ↵

- Harry Oxorn, H.B. Atlee, M.D. (Hantsport 1983) pp. 40-1, 275-5; Carl Tupper, “Atlee,” in Nova Scotia Medical Bulletin (Dec. 1978), pp. 161-3. There is an extensive bibliography of Atlee’s writings in Harry Oxorn, H.B. Atlee, M.D. (Hantsport 1983), pp. 345-52. ↩ 13. Harry Oxorn, H.B. Atlee, M.D. (Hantsport 1983), pp. 276-7; H.B. Atlee, The Gist of Obstetrics (Springfield 1957), p. 24. ↵

- Harry Oxorn, H.B. Atlee, M.D. (Hantsport 1983), pp. 276-7; H.B. Atlee, The Gist of Obstetrics (Springfield 1957), p. 24. ↵

- Letter from A.R. Colwell to A.S. MacKenzie, 4 Nov. 1925, President’s Office Correspondence, “Medical Faculty, 1921-1931,” UA-3, Box 279, Folder 1, Dalhousie University Archives; also Halifax Mail, 25 Nov. 1925. ↵

- Senate Minutes, 14 Apr., 11 May 1908, Dalhousie University Archives. A new history of dentistry at Dalhousie has been a great help. See Oskar Sykora, The Maritime Dental College and the Dalhousie Faculty of Dentistry: A History (Halifax 1991), pp. 26-39. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 29 Mar. 1922; letter from A.S. MacKenzie to Learned, 11 Feb 1922, President’s Office Correspondence, “Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1918-1922,” UA-3, Box 173, Folder 6, Dalhousie University Archives; Board of Governors Minutes, 28 Apr. 1922, UA-1, Box 15, Folder 3, Dalhousie University Archives; Sykora, Dalhousie Dentistry, pp. 69-70. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 1 Nov. 1922; for student statistics, see Annual Report of the President, especially for 1911-12 and 1924-5. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 8 Nov. 1922; Senate Minutes, 16 Jan. 1923, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 31 Jan., 14 Feb. 1923; A.S. MacKenzie, "A Parting Word to the Class of 1924," President’s Office Correspondence, “Student Publications, 1921-1931,” UA-3, Box 347, Folder 8, Dalhousie University Archives; On the university year, see Senate Minutes, 20 Oct., 11 Nov., 14 Dec. 1922, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Senate Minutes, 9 Jan. 1923, Dalhousie University Archives. There was a further three-hour debate on dances on 20 Jan., which ended with the rules virtually unchanged. ↵

- For Rex cigarettes, Gazette, 9 Mar. 1928; for the jokes, 18 Oct., 18 Nov. 1922. ↵

- elegram from A.S. MacKenzie to Margaret Lowe, 29 June 1923; Margaret Lowe to A.S. MacKenzie, 1 May 1930, President's Office Fonds, "Margaret Lowe," UA-3, Box 95, Folder 26, Dalhousie University Archives; Dalhousie Gazette, 15 Oct. 1924; Halifax Morning Chronicle, 10 Aug. 1921, reporting Mrs. Eddy’s speech to Dalhousie students of October 1920. ↵

- Telegram from A.S. MacKenzie to Frank Darling, 18 July 1919, President’s Office Correspondence, “Frank Darling, 1911-1920,” UA-3, Box 313, Folder 4, Dalhousie University Archives; A.S. MacKenzie to C. Thetford, 20 Dec. 1921, President's Office Fonds, “Frank Darling, 1920-1923,” UA-3, Box 313, Folder 5, Dalhousie University Archives; R.B. Bennett to A.S. MacKenzie, 28 Apr. 1922, from Winnipeg; Bennett to A.S. MacKenzie, n.d. but probably 11 Dec. 1922 from Montreal en route to England, President's Office Fonds, "R.B. Bennett, 1912-1928," UA-3, Box 40, Folder 8, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- A.S. MacKenzie to R.B. Bennett, at Calgary, 17 Oct. 1923, President's Office Fonds, "R.B. Bennett, 1912-1928," UA-3, Box 40, folder 8, Dalhousie University Archives; Dalhousie Gazette, 2 Apr. 1924. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 14 Jan. 1925; the comment on bobbed hair, 3 Dec. 1924. ↵

- Campbell to A.S. MacKenzie, 9 Oct. 1924, from Calgary; Bennett to Campbell, 10 June 1925, letter and telegram; Campbell to A.S. MacKenzie, 11 June 1925, telegram to Ottawa, President's Office Fonds, "President's Residence 1924-1959," UA-3, Box 238, Folder 2, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Campbell's memo, President’s Office Fonds, “Committee of Nine, 1926-1935,” UA-3, Box 254, Folder 5, Dalhousie University Archives. The committee originated in a letter from the Alumni Association commenting on some lack of cordiality between students and staff. Campbell believed the Alumni could act as a cementing body between students and staff, hence the three Alumni members of the committee. ↵

- Senate Minutes, 4 May 1925, Dalhousie University Archives; Dalhousie Gazette, 4 Feb. 1926. For the information of the Students’ Council of 1912, see P.B. Waite, Lives of Dalhousie, Volume 1, p. 372. On professors who found it difficult to stop their lectures on time, see Dalhousie Gazette, 25 Nov. 1925 and 28 Jan. 1926 when it was the subject of an editorial. On library hours, see Gazette, 11 Mar. 1926; the hard-hitting editorial is 4 Nov. 1926. The consequences are described by A.O. Hebb, 16 Jan. 1991; his three letters of reminiscences to P.B. Waite, 14 Dec. 1990, 16 Jan. and 20 Feb. 1991 have been most useful, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 3, Folder 8, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Dalhousie Gazette, 4, 11 Mar. 1926; letter from David Soloan to A.S. MacKenzie, 17 Mar. 1926; A.S. MacKenzie to Soloan, 22 Mar. 1926, President's Office Fonds, "Student Publications, 1921-1931," UA-3, Box 347, Folder 8, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- A.O. Hebb to Peter B. Waite, 16 Jan. 1991, Peter B. Waite Fonds, MS-2-718, Box 3, Folder 8, Dalhousie University Archives; Dalhousie Gazette, 13, 27 Jan. 1927; the poem is Gazette, 11 Jan. 1929. ↵

- For obituaries of Campbell see Dalhousie Gazette, 25 Nov. 1927. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 8 Oct. 1929, UA-1, Box 5, Folder 7, Dalhousie University Archives. Dalhousie’s financial statements and questionnaire answers prepared for John Price Jones give an useful perspective of Dalhousie finances in 1929. They are in UNB Archives, R.B. Bennett Papers, vol. 907, nos. 568770-7. Library and Archives Canada has microfilms of the UNB collection. R.B. Bennett was appointed to the Dalhousie board in July 1920 and attended his first meeting on 28 March 1922. ↵

- The proportion of mortgages in Dalhousie’s portfolio was changing. In June 1929 it had been 19 per cent; the board’s finance committee felt that was too high, and while no money had ever been lost on Dalhousie’s mortgages, one or two big ones were renegotiated that summer and the proceeds reinvested in government bonds. Board of Governors Minutes, 8 Oct. 1929, UA-1, Box 5, Folder 7, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵