Chapter 1 ~ Beginnings

My great grandfather, my grandfather and my father were all Customs officers. So were my uncle and brother. And when I had spent 11 years in the same Customs service, I decided it was time to make a break with the family tradition. So I resigned, became an emigrant and took a boat to Canada.

The day I arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, a local newspaper advertised a vacancy on its staff. I applied and got the job and became what I had always wanted to be, a newspaper reporter.

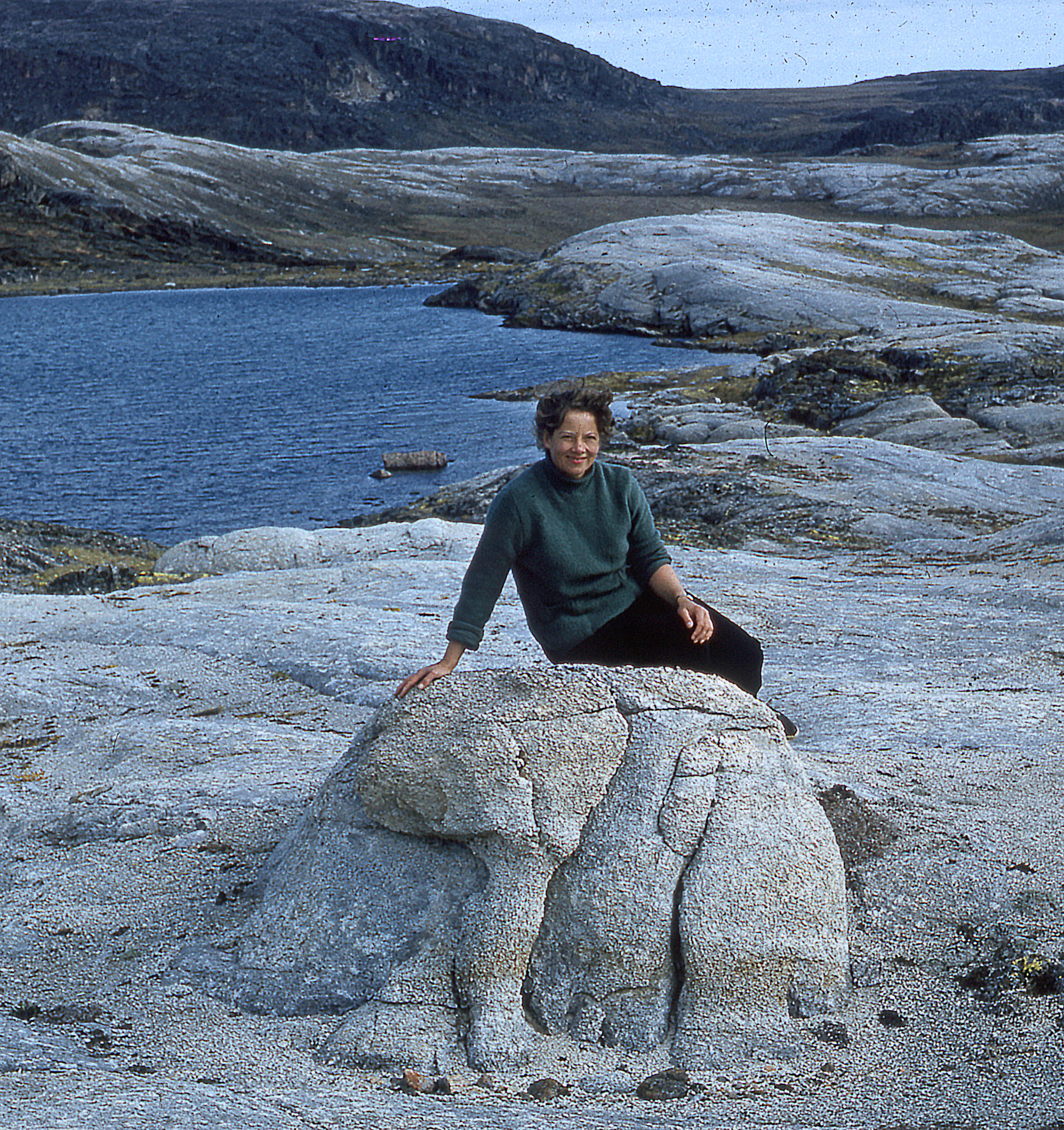

Three years later, in September 1959 I was asked to speak at the triennial meeting of the Canadian women’s Press Club in Ottawa. Within five minutes of my arrival at the Chateau Laurier Hotel, I met a fellow English woman, Rosemary Gilliat, a photographer, and within an hour we had discovered both of us were bent on going to the Canadian Arctic, so we resolved to go together as a team, she would take the photographs and I would do the writing.

The following spring, I cashed my Canadian savings, sold my car, sublet my apartment, found a foster home for Henrietta, the cat, and bought a tape recorder, because I decided to break into radio as well. For her part, Rosemary bought a cine camera with the intention of going into film production. We were both very earnest.

Anyone who has been on a week’s camping trip would understand the extent of planning a four months’ journey in unfamiliar Arctic regions. We had to be prepared for extremes and our organisation was complicated by the fact that we lived almost a thousand miles apart. I lived on the Atlantic coast and Rosemary lived in Ottawa, which was near the government offices with which we had to deal. Consequently, the bulk of arrangements about transport and the freighting of supplies fell on her shoulders. Rosemary was experienced in camping, so it was she who listed the equipment we needed and she who bought most of our supplies and had them shipped to Cape Dorset in West Baffin Island, where we hoped to spend the Arctic Summer.

I was to take on the plane enough of life’s necessities to tide us over the first few weeks. Accordingly, I presented myself at the store of a ships’ provender in the old seaport of Halifax. My needs were listed on the back of an envelope. A young, beardless clerk approached me first but on learning my destination, he put me in the hands of the old proprietor who had outfitted ships from Newfoundland to New Zealand.

“Take lots of spices,” he said when I named our prime staples of dried potatoes, tinned beef and prunes.

Later, I learned Rosemary had shipped an enormous quantity of tuna fish. She could not eat tinned beef and I did not like tuna fish, so we were doomed to chewing our way through one of the most monotonous diets ever taken North.

Advice was plentiful. I was told to take lots of mosquito netting; how to treat frostbite; to be ready for rain, and a subscriber to the legend that the Arctic is paved with gold assured me I would “make a pile” because in the North there was nowhere to go and nothing to spend money on.

On June 14, 1960, I arrived at Montreal airport dressed in tennis shoes, rock climbing pants, yachting anorak, ski mittens, tweed socks and carrying a bee keeper’s hat. My pockets bulged with bottles of fly repellent.

“We,” I thought, “are ready.”

In addition, I carried a rucksack, a suitcase, a typewriter and the tape recorder. Going North is referred to by “those who know” as going Inside. When you are North, the South is named the Outside. This helps to maintain the exclusive club atmosphere, which has been nurtured by bearded scientists, prospectors and traders, and discourages women from entering the Arctic, except for nurses and school teachers. They are functional. We were to serve no cause but journalism, and in respectful deference to the club we were entering and whose members we may have to entertain, we included a little whisky amongst the apple rings and flaked onions.

Exhausted with excitement we presented ourselves at the Dorval air terminal on the morning of departure and joined a queue of engineers, stevedores and black coated missionaries. We shuffled towards the ticket agent’s desk and a suave, silver haired clerk asked us to wait. When everyone else had disappeared on to the plane, he approached us, sad eyed and courteous, and explained there were too many people for the plane and would we mind waiting until the next day.

We were too stunned to protest and flopped down among our baggage. It was the first lesson in patience, a virtue required by all Arctic travelers who may find they have to wait weeks at a time for transport.

A succession of delays followed, but two days later we boarded a flight for Frobisher Bay, and surrounded by our kit we settled down for the six hour journey North. My seat was close to the door, which communicated with the cockpit and I could hear voices. Someone distinctly said, “You’ve got to mend it.” There was a sound of heavy hammering. A frowning mechanic opened the door and rushed off the plane. My eyebrows rose. From within a voice asked, “How long does the run take?” Someone answered in a quiet mumble. “Then you’ll have to mend it,” the first voice said. A cool looking stewardess emerged wearing a reassuring smile and announced to the eight passengers: “They’re just mending the pilot’s seat. We won’t be long now,” and passed down the narrow gangway.

The hammering stopped and out stepped a flight engineer in a white overall and carrying a tray of tools. He looked confident and gave me a brave smile, but he got off the plane. Down on the tarmac someone gave the thumbs up sign to the pilot, the plane throbbed and shuddered. Within minutes we were above the roof tops of the air terminal buildings, past the toy sized houses below and into the solitude of a cloud bank.

The fuselage had a very businesslike interior. Seats were anchored on only the port side and mindful of the months of close cohabitation ahead of us Rosemary and I selected seats at opposite ends of the plane. On the starboard side, freight was stacked high and lashed down with rope nets and steel wires. There were packing cases of char nets, fishing lines, filter tip cigarettes, sleeping bags and baby food. A coffee urn bearing the instruction THIS WAY UP was stacked among eight cases of Encyclopaedia Britannica. It looked as though things were not going to be so primitive after all.

Most of the journey was passed in a glare of brilliant light shining on the landscape of cloud below us, but after five hours we emerged from the pillars of cloud and we were flying over Polar seas. Below, ice shimmered on Ungava Bay cradled in the coast of Northern Quebec. Viewed from such a distance, the ice looked like a giant specimen slide seen through a microscope. Cell formations of turquoise and white ice seethed in black streams of icy water and passed beyond the frame of the plane’s porthole. Turgid and sluggish, the floes lay close packed like a frozen blood stream, waiting to flood into life in the Arctic Summer, when sunlight gives the North no night and twenty four of day.

Years of hearsay and impressions garnered from books were suddenly crystallized in that first sight of those icy seas and I found the reality no disappointment. I knew I should relish the North.

Our immediate destination, Frobisher Bay lay at the head of a two hundred mile long bay that penetrated the South East corner of Baffin Island, fourth largest island in the world if you do not include Greenland.

As we lost height flying up the bay, we could see to the East black hills white-dappled with snow. To the West, ice caps glistened on the mountains of Meta Incognita – Beyond the Unknown – named by Sir Martin Frobisher, the doughty Elizabethan navigator who searched for a North West passage to the riches of Cathay.

Ahead of us sprawled the Eskimo camp of Iqaluit and the township of Frobisher Bay with its Polar route airport, gateway to a summer full of the promise of excitement in the wide, cold North which every greenhorn Artic traveller imagines is certain to be found.