Chapter 26 ~ How to Catch a Fox

Sleeping in a tent was wonderfully pleasant and relaxing in fine weather. The air was keen, the sounds of the birds always fell kindly on the ear, the soil and plants were earthy to smell and close to touch, and the tent door opened on to a free, wide Arctic world. The thin layer of white canvas about us gave a protection far beyond my expectation, and everything went well until suddenly the weather deteriorated rapidly and brought rain and snow, and the rising winds began to undermine my feeling of security. The winds blew at their worst at night, which was extremely inconvenient. Not only did we have to turn out of our warm sleeping bags to adjust the guy ropes, but we had to do it in pitch darkness, often in driving hail, snow or rain, and we also had to dig with bare hands for more and more rocks to anchor the original tent ring. The rocks lay like icebergs, nine tenths submerged in the ground.

On such nights, Rosemary usually wakened first and had dressed in a waterproof smock and was fumbling for the flashlight before I had roused from inside my two eider down sleeping bags. So Rosemary became a better boulder roller than I, through more practice. We almost lost the tent one night, when the sensation of being hit with a wet dish cloth wakened me and I sat up inside a slapping, collapsing tent.

We both scrambled outside in pajamas and little else to save the ridge poles falling to leeward through the wind redistributing the stones. The wind had gusted so strongly that all the windward guy ropes and their enormous anchors had been blown out of position.

Our home was going West.

It took an hour in soggy pajamas to pitch the tent properly again, and when we arrived in the settlement the next day, nerve frayed through lack of sleep, we learned we had not been alone in our troubles. Even some of the Eskimos tents had been blown down and their tents were pitched lower and had seemed more protected than ours.

A few days later when I took my turn to go for the morning jugs of water, I found the stream was frozen into a thousand sparkling crystals. I dashed back to tell Rosemary to bring her cameras before the sun had a chance to melt them. From then on, we collected our water supplies at mid-day, by which time the sun had usually thawed the ice. In deep winter, the people cut blocks of ice from the frozen lake and carried the water home in lumps on a dog sled. Until Jim Houston kindly supplied us with a small oil heater, our only source of warmth was generated by the cooking stove. Stove fuel was not in great supply, so we could not keep it alight any longer than neccessary and the temperature soon dropped once cooking finished.

It was the day after the arrival of the Judicial Party that I succumbed to a sickness which was sweeping through the Eskimo tents. Its symptoms were troublesome – vomiting, spotty tonsils, temperature and endless trips to the tundra in the night, so I was committed on to a bed in the nursing station, which gave me time and opportunity to dry out my clothes and my two sleeping bags.

I wrote in my journal for September 12, “It’s heaven to be dry again.” The constant damp and rain had seeped into all our kit, and there was no way of drying things inside the tent unless the weather improved. It was “between seasons” and the year’s most miserable time for tent dwellers. The weather was cold and wet and the Eskimos put on their clothes in the morning, only slightly less damp than they had been when they were taken off.

While I was in the nursing station, I expected to be joined by the baker’s young wife but she failed to arrive. She had been on the brink of motherhood since our arrival in Cape Dorset, but she was still plump and pregnant when I emerged from the nursing station a few days later.

The mother of the baker’s pregnant wife was Ikaluk, the Houston’s housekeeper, and one evening when Rosemary and I were preparing a dinner for Jim Houston after his wife’s departure on holiday, Ikaluk came bounding into the house in her sealskin boots and with a bundle in the hood of her parka. She bent over, shot the swaddled baby over her shoulder with a heart stopping velocity and announced she was a grandmother.

Ikaluk said we were welcome to go and see her daughter in one of the tents in Chapel Valley, so the following day I set off to visit the family.

As I forded the shallow stream running between the tents, a familiar featured girl passed me, stepping out briskly. She nodded and smiled and she had gone out of sight up the rocks when I realised the slim girl who had-just gone by was the new mother.

Confinement was a simple thing in a simple society.

Her baby was as pink faced as a White woman’s infant, for Eskimos are not dark skinned. Their exposed faces and hands become brown and weather beaten because of their mode of life, just as any farmer is tanned and ruddy complexioned.

In infancy, they have a telltale “Mongolian spot” which is a dark bluish tinge in the skin at the lower part of the spine. It covers an area the size of an egg and fades as they grow older. The Mongolian spot is common to most Asiatic peoples, to some Balkan Europeans and to the Eskimos, and is an indication of the migration of the Asiatic peoples, Balkan people born with the mark are presumed to have descended from the Asiatic tribes which migrated into Europe at the disintegration of the Roman Empire.

Arranged marriages were common in Cape Dorset, and trial marriages lasted up to six months. Although the Eskimos were not known to have any artificial form of birth control, children born of trial marriages were almost unknown.

For the “probationary” period, the couple lived in the tent of the girl’s father, and if they decided to become man and wife, they moved into their own tent and they were then recognised by their own people as married.

Any wedding service performed thereafter by a White missionary was simply a religious conformity, nothing more and nothing less. An Eskimo woman was not valued on such qualities as face or figure as often is the case in a White man’s society. The most desirable social values were an ability to sew well, and to tend a seal oil lamp, and when an Eskimo bride entered the tent which was to be her home, the most important possessions in her trousseau were her sewing kit to make her husband’s clothing and a kudlik, or soapstone lamp. The lamp was vital in their lives, it gave them light, warmth and over it, blubber was rendered for oil and their food was cooked. The Eskimos had a saying that if the flame of a lamp died, then life also died in the tent.

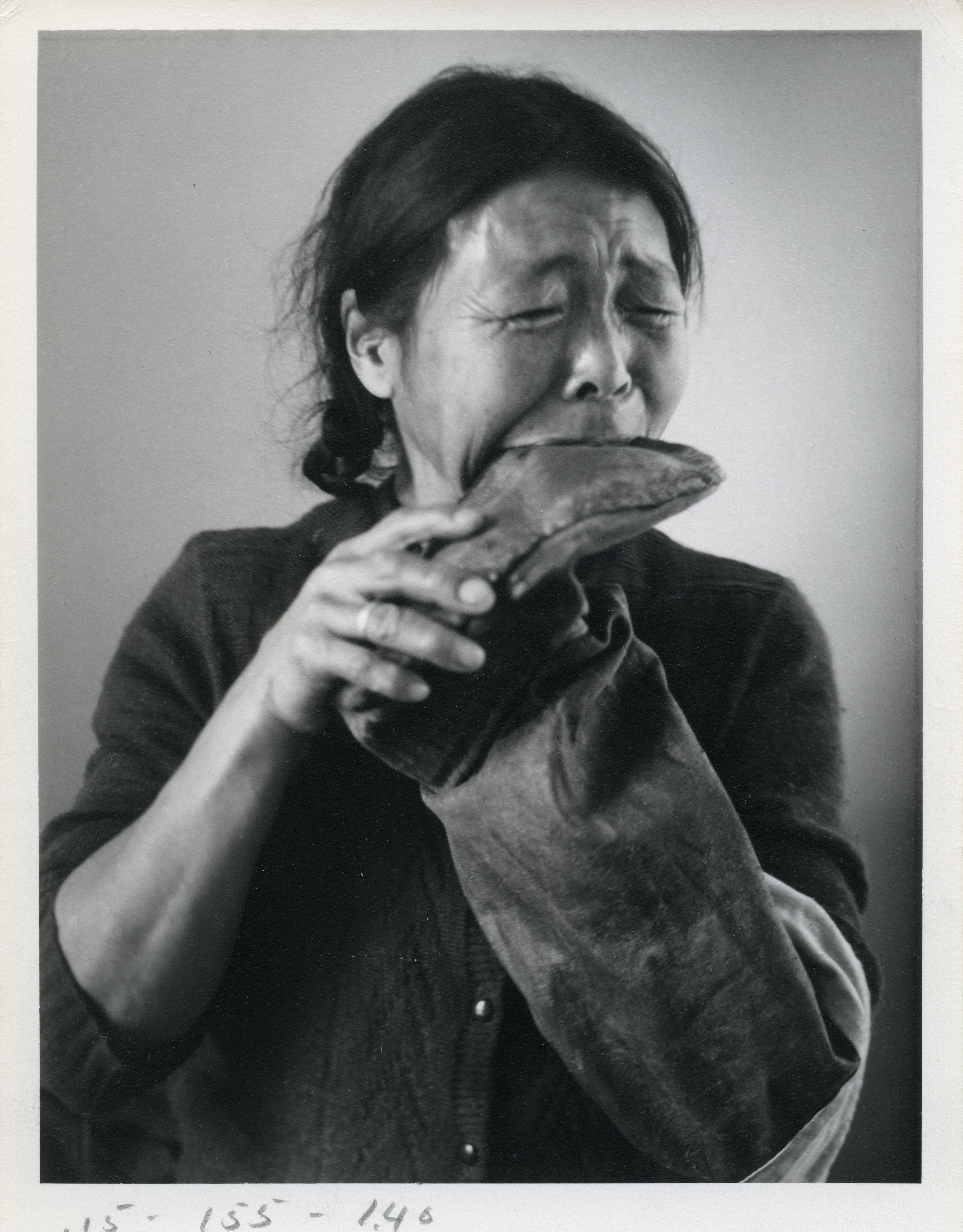

The sealskin boot was the foundation of seal hunting economy. The leg of the boot was made from the supple skin of a silver jar seal or a harp seal, and the sole was made from the tough skin of an udjuk, or square flipper. The seams were sewn with threads of dried caribou sinew which swelled when the boot was immersed in water, thus filling the hole made by the needle and keeping the wearer’s foot warm and dry. It was worn with warm linings of socks made from duffle cloth, and duffle cloth slippers and was ideal for the constant stepping in and out of shallows when travelling by boat, and for moving through snow in winter.

According to Jim Houston, the people In Frobisher were lost because there was no hunting and so no Kamiks and the women no longer were required to use their traditional skills. Rubber boots were bought from the store and the people were beginning to wear shoes. Men and women had lost their roles in what had recently been an integrated society, with its own well-defined duties.

One of the most successful hunters and trappers living in Cape Dorset was named Pitsolak. He was a man in his middle fifties and still very handsome. His charm was so polished that I suspected he was something of a plausible rogue.

Pitsolak was clever and he spoke and understood more English than he would admit. His camp was well organised and he asserted superiority over other Eskimo men, some of whom were dependent on him. When first we sailed into Cape Dorset from the luxury camp at Tellik, we were overtaken by a well founded Peterhead boat lying low in the water. It was Pitsolak’s boat, loaded down with a big catch of walrus. The walrus meat was to be used to feed his dog teams and Pitsolak was assured of getting his huskies in good condition by the time the snow lay thick enough to set his trap line.

He was the first with walrus meat and so he was ahead of the other trappers in the settlement and would become the richer when his traps snared white foxes – still one of the most valuable Arctic furs traded with the Hudson’s Bay Company, fetching about twenty dollars an average skin in 1960, according to the trader. The trader had outfitted Pitsolak’s walrus hunt. He had no hesitation in doing so. With Pitsolak, profit was assured. The man even looked prosperous. He had gold fillings in his teeth and sported at least three parkas – a sure sign of material wealth. He was the only fat Eskimo in the settlement and he had a magnificent set of teeth, which I learned were false.

Once when they were broken, he took them to the nursing station and asked that they be sent out for repair. He was told it would cost a lot of money.

“That’s O.K. I want two gold teeth as well.” said Pitsolak.

The teeth were flown out, mended, studded with gold and when he called to collect them, he paid the bill immediately and without demur, put them in his mouth, flashed a smile at the nurse and said, “Nakoame.”

The missionary had formed a friendship with Pitsolak some years previously while he was still at Lake Harbour. Pitsolak had fallen foul of the law and instead of being sentenced to prison for his offence, the judge banished the Eskimo from Gape Dorset for two years. In his wisdom, the judge realised a term in prison, being served three meals a day and seeing film shows, was no punishment to an Eskimo. By banishing him, Pistolak was made to lose face among his own people – a far worse penalty.

The offender went with his wife to Lake Harbour, and there the missionary counselled him and the “criminal” and the churchman became friends.

Later, when Mr. Gardner was transferred along the coast to Cape Dorset, Pitsolak was already home again and any face the Eskimo had lost must have been immediately restored when he gave the missionary the welcome of an old friend.

During choir practice, Pitsolak usually took charge of the proceedings and translated for me, bossing the singer with authority, and leading the honors with a strong, pure voice.

The missionary lived in a small hut while waiting for a house to be built for himself and his family. It was a humble little dwelling but it was heated by an efficient oil stove and it had a touch of luxury in the shape of a naked electric light bulb in the centre of the ceiling. (Electricity was generated by a spasmodic diesel engine.)

It was only a one-roomed hut, but it held a lot of people and the callers, myself included, used to cram inside until its walls streamed with condensation and the smell of wet sealskin forced even the Eskimos to open the door for ventilation.

Pitsolak was a frequent visitor, sometimes alone, sometimes with his patrician-looking, thin-lipped wife Ageak. He arrived one evening when I was there, making a bold entrance in a rainstorm. He was wearing the one and only check parka in Cape Dorset and a pair of bright red waterproof trousers over his thick pants. If bowler hats and rolled umbrellas were ever put on sale by the HBC as status symbols, Pitsolak would have been the first to own them, I am sure. Mr. Gardner took the mittens from Pitsolak and Ageak, and Pitsolak made himself comfortable on the missionary’s bed. Ageak was just about to lower herself on to an offered seat, when a barked order from her husband stopped her in aid air.

She went to him, knelt on the floor at his feet and helped him off with his waterproof trousers, she hovered a little to see he wanted no more attention and at last sat down. It was easy to see the man had probably earned his reputation as a wife-beater and a tyrant towards his slaves in his camp – men who served him hoping he would leave them enough meat in the tail end of the stew pot.

Pitsolak’s boat had been hired by the Department of Mines and Technical Surveys, and he told us he objected to his crew being paid wages. He said it was his right to handle the money. It was his boat and he could use it only forty days or so out of every year and it was a waste of good hunting time when the party of geologists hired it. He recalled the days when white men had hired his boat and his crew had been paid in nothing better than cigarette ends. He was a great traveller, and it was not until Pitsolak, more forthright than any other Eskimo I met, questioned me about myself and my journeys and purpose, that I realised the enigma of visiting White people among the Eskimos. We had arrived without introduction, we observed them, photographed them and then left with precious little explanation.

Perhaps because of his boldness, because of his ability to speak English and because we were women Pitsolak told us why he was such a successful fox trapper, when I asked him. He was coy and giggled at first and asked the missionary, in Eskimo, for the English words meaning “fox lair.” Then he explained how he had become the Hudson’s Bay trader’s best trapper in Cape Dorset.

First he had to find a fox lair and from it he gathered foxes’ frozen urine or droppings. Then he baited his first traps with it, and if any fox passed within sniffing distance it would find the smell irresistible. When the first foxes were caught, there were always droppings in the traps and so he could bait the rest of his trap line. It was bad if he could not find a fox lair at first, but, said Pitsolak, he was not defeated. He knew of a substitute which was almost as good, and he named a certain soap and said he bought some tablets of it from the trading post and used small pieces from it to bait the traps. The soap had been advertised for years as removing from the body that smell which even best friends would not care to mention. As I picked my way home that night, I fell to wondering what a well-washed white man smelled like. Not only to Pitsolak, but to foxes as well.