Chapter 19 ~ Polar Bear Stew

Frobisher Bay was in a hubbub of activity in August. The annual Sealift was in full swing and every store house and larder was being replenished with its year’s supply plus the hundreds of sundry commodities needed to keep a small town functioning in an entirely unproductive land. Food, building materials, clothes, boats, fuel and even motor cars were listed in the freight.

There were no docks, no berthing piers and no machinery for unloading HBC dry cargo, so every item was transported to shore during high tide. As the flat-bottomed barges grounded on the beach, scores of Eskimos, men, women and children grabbed sacks and cartons to carry them above high water mark to the warehouses of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The words “dockers’ strike” have not yet been translated into Eskimo language.

The children liked to carry sugar bags, the older ones carrying fifty-pound sacks and the younger carrying five-pound bags. Some of them would burst open a corner and tip a handful of contents into a rag, screw it into a ball and suck the sugar as other children suck a lollipop.

The Eskimos worked the tides both day and night in a happy confusion, drinking tea and eating hard tack biscuits for sustenance in the HBC warehouse while waiting for the next barge or the incoming tide. Only bad weather could stop the unloading, and inevitably the bad weather came. A constant south wind plucked summer’s outgoing ice from Hudson Strait and blew a million ice floes up Frobisher Bay until the waters at its head were choked from shore to shore with a field of translucent green and turquoise floes that chilled the air and sealed off every passage between supply ships and shore.

Work was held up for a week.

At this time, Rosemary received some mail from the Outside, including some reels of colour film, exposed at Port Burwell. They had been sent out for processing. At first glance, the film was excellent, but as she held it to the light, she discovered her perfectly exposed shots were ruined by scratches which extended throughout every inch. Her unrepeatable story of the Port Burwell char industry was irrevocably disfigured. The camera was diagnosed as having grit in the “gate.” It was a great blow but she accepted it with an amazingly stoical, “It can’t be helped,” which was English for the Eskimo expression, “Iyungnamut.”

It seemed to be the day for producing a delicacy which I had secreted, at the bottom of my kitbag more than two months before. It was a Camembert cheese, intended for a rainy day, and husbanded in a tin. The time was ripe. And so was the cheese.

We had it for lunch with a batch of freshly made oat cakes. It was our main and only course. We sniffed it, and we savoured it. I carefully cut it into exactly equal halves with all the relish of Ben Gunn, who dreamed of cheese for years on Stevenson’s Treasure Island. I put the two halves on two plates, served them and slowly ate all my half. Rosemary sat in front of hers and cut the rind from the cheese and said she would eat only half that day and the remainder on Sunday. “Oh no you won’t,” I told her, thinking of a cheeseless morrow. The prospect of smelling Camembert and not having any was too unkind. The problem was soon resolved however, for after Rosemary gave me her cheese rinds, she decided it was not really such a big piece of cheese after all and she ate the lot.

On our next trip to Apex to see the unloading, we met Spyglassee, and to our delight we were invited on another hunting trip down the bay. We were no longer ignorant of the hazards of a life on the ocean wave, but we decided we could not refuse such an opportunity. So we said, “Yes,” and went home to pack our gear once more. We solemnly wrote out letters to be opened in the event of our non-return and left them in our bedrooms, beyond the glance of casual callers during our absence. Chastened by our previous sea trip, we thought it would be of help to the authorities if they knew how to dispose of our equipment should they have to.

Two boats were to go on the seal and walrus hunt and it was to last three days. It seemed an excellent way to fill in the time while we waited for better flying weather to get into Cape Dorset – our next assignment. We made a rendezvous with Spyglassee and the hunters, on the shore, in front of the HBC warehouse, Tuesday, August 11, and we accordingly presented ourselves for cooking duties, or anything else useful, at two o’clock on a day of powder blue clouds, mist and flat calm sea.

The bay was so thick with ice, that to us it seemed impossible to float a boat – there just was not enough water. We were detailed off in the Tookak with Mike, the leading hunter, while Spyglassee, Mosesee and another man were to take the open whaleboat. Flimsy canoes ferried us to our respective boats, daintily picking their separate ways through the mass of ice. Once on board the Tookak, it seemed a vain proposition to reach open water, the floes towered so high and thick.

A man was sent aloft to spy out a route, Mike started the engine and the boat moved forwards, slithering between floes, nosing into leads and forcing a narrow channel. Sometimes we were brought to a halt, stopped against an ice pan. Then Mike lodged the Tookak’s bow against the obstacle started up the engine again and pressed it out of the way.

By half past five we found open water.

Mike spurred the boat to full speed ahead and we leaped into the crystal-clear water with a tremendous sense of freedom and space. Our spirits rose as we left behind us the ice and the sprawling ugliness of Frobisher with its guilty debris of Eskimo civilisation.

Out on the water once more, the incidentals of a sophisticated chromium-plated economy gave way to the fundamentals of simple living, and we settled down to a shipboard routine, which was going to depend for sustenance more and more on the hunter’s skill the longer we stayed out. Life was untrammelled and gay in Eskimo society and I had no care about how long we stayed at sea.

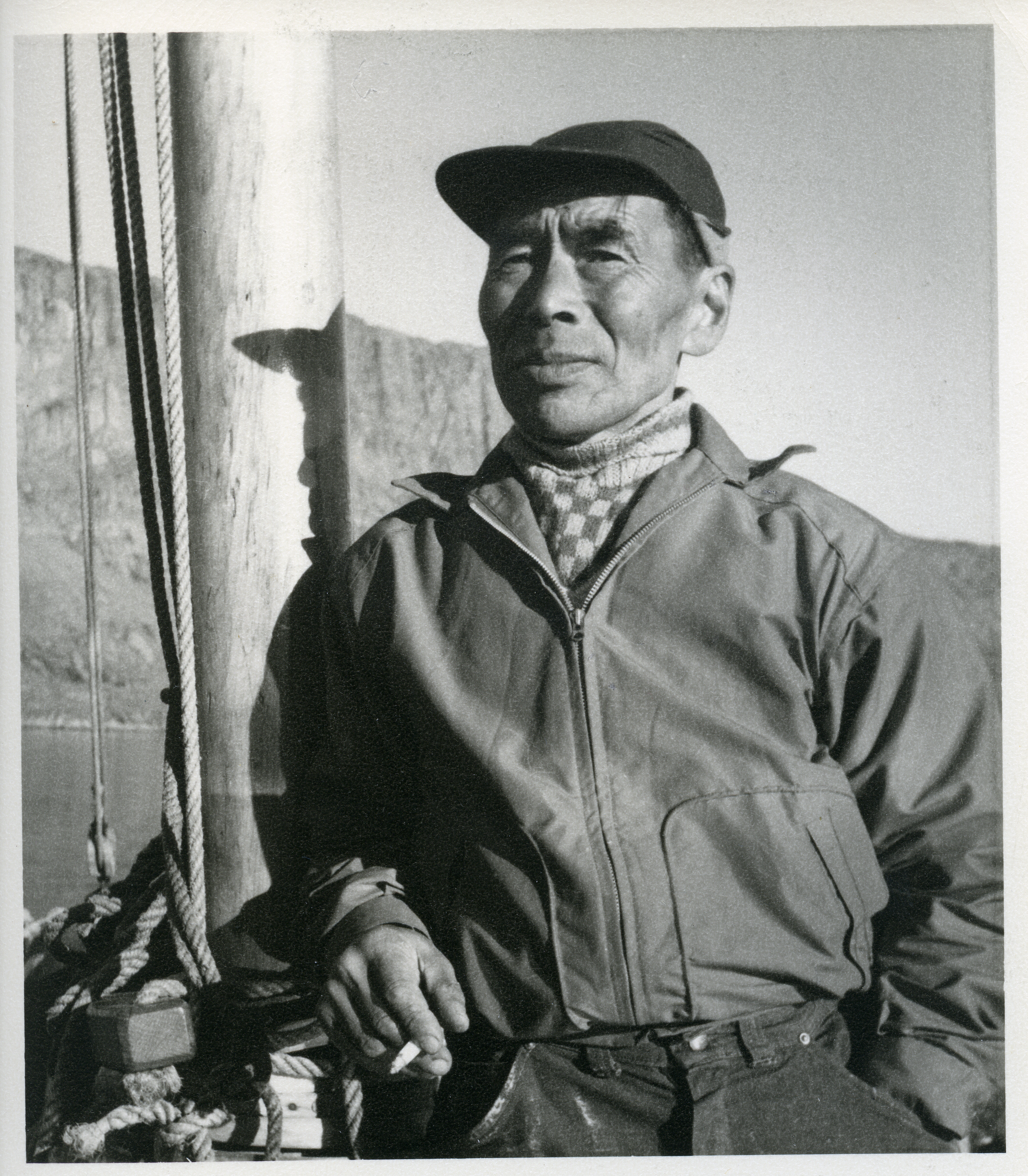

Apart from ourselves and Mike on the Tookak, there were his eleven year old son Mosher; Pitsolak the helmsman and his son Sapinak; Isaak, who was a poor shot but a merry one; and Eetuk, who was a crack shot and a renowned polar bear hunter from Hudson Bay.

Eetuk was also well known in Frobisher for another reason. Six months prior to our journey, he had been given up for dead after suffering a heart attack. His pulse rate had been a feeble twenty-eight, and his relatives were so sure he was dying that they had begun to mourn, sitting by his sleeping platform. Bob Green, superintendent at the rehab centre, went to Eetuk’s home, and Eetuk rallied. Resuscitation was begun and to everyone’s astonishment, Eetuk recovered. He was a mild natured man and took up the age-old position of watchfulness with the other hunters in the bow of the boat. The whaleboat was ahead of us and hugged the shoreline more closely than Tookak, and the three men aboard it seemed to find life a very gay affair. We could hear them laughing and their journey was punctuated by stops for tea. We could see the kettle spouting steam and the enamel mugs being passed round when we picked them up in the sights of the binoculars.

There were more seal in the bay during August than there had been in July. Soon, after leaving the ice floes we startled a small herd of a dozen or so. They were rolling and playing in the water, singing with little moans and swooshing water through their whiskers, but as we bore down on them, they submerged, and neither boat successfully shot any.

Mike injured one, but by the time Tookak glided into the brilliant scarlet patch of water, only a thin stream of bubbles riffled the surface. The seal had sunk immediately.

There was no chagrin on the men’s faces; only a long-drawn “eee” of disappointment, a self-conscious laugh from Pitsolak at the helm and the quiet direction from Mike to carry on down the bay.

Spyglassee’s boat was at the anchorage rendezvous first that night. Neither boat had made a kill, and we clambered down into the Tookak’s hold for a dinner of tinned pork, beans and vitamin biscuits sprinkled liberally with caribou hairs. Mike boiled a kettle cold water and tea leaves in a brew-up strong enough to tan rhinoceros hide. There were more people than tin mugs, so he insisted Rosemary and I drink first with the two children. The tea was inescapable. I switched off my sense of taste, swallowed hard and handed the empty mug back to Mike. He did not stop to wipe it on his sleeve, but poured himself a mugful and sat back content.

The occasional dish washing was a perfunctory matter of a splash in sea water and a wipe with a rag, if there was one, which seemed to distribute the omnipresent caribou hairs more effectively. It seemed that once caribou sleeping robes were put aboard ship, the hairs wafted into every crevice and cranny and no meal was complete without them.

The seven hunters, Mosher and Sapinak slept in the Tookak’s hold that night while Rosemary and I had the fo’c’sle. As we turned in, Mike padded along the deck and cheerfully offered me the communal “honey bucket” with honest to goodness Eskimo hospitality.

“Who could ask for anything more?” I said to Rosemary.

A long way away, I could see a lonely tent, yellow with warn lamplight ashore. I washed my face in sea water by the light of the moon, dressed up in my warmest togs and retired to my sleeping bag, thoroughly aware I was supremely happy.

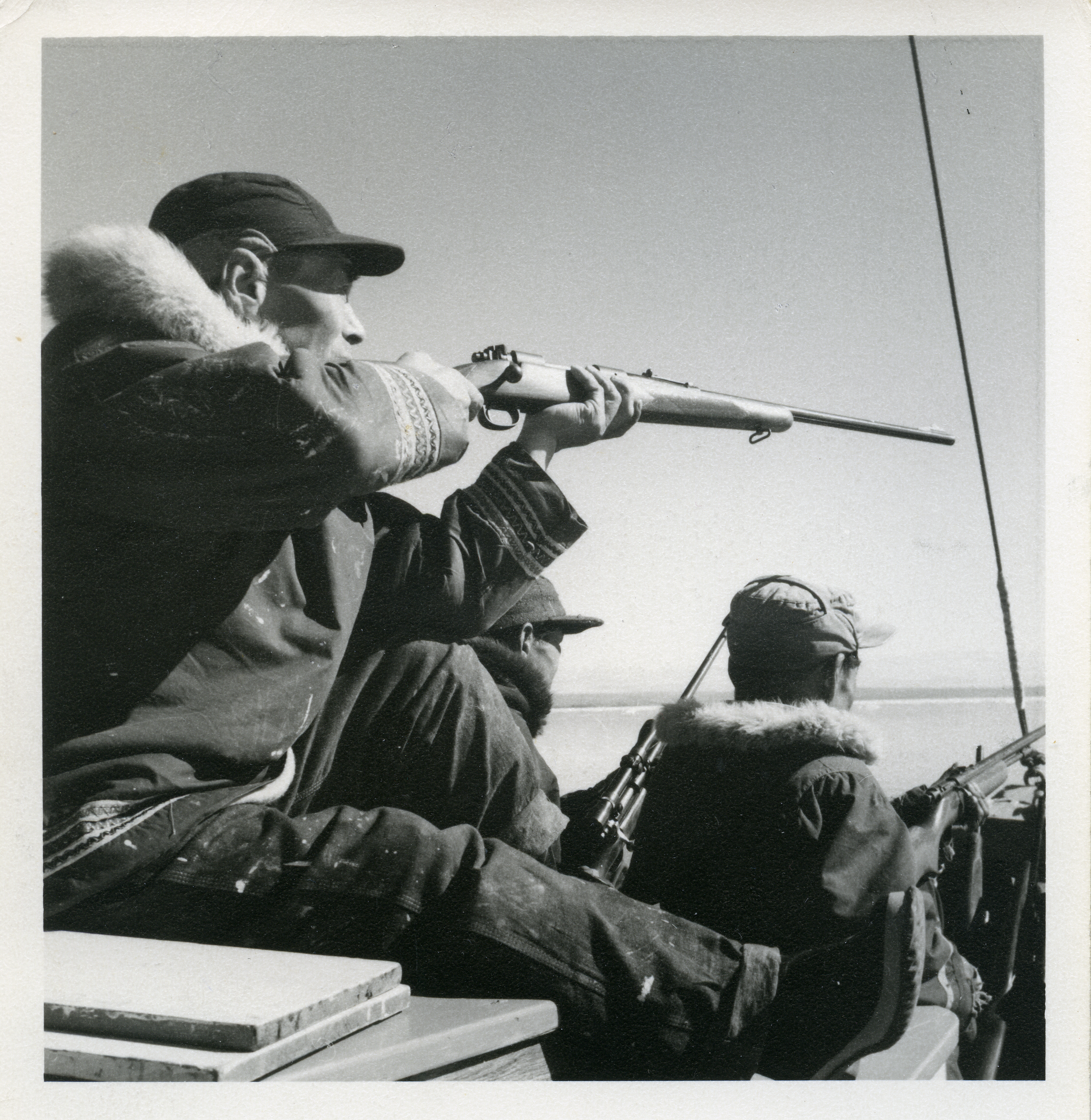

I awakened at six o’clock to the sound of someone using a rasp on metal overhead. It was Eetuk, filing the V-sight on his rifle and making attracting noises at a band of seals cavorting in the water nearby. A shot rang out, followed by the Eskimo equivalent of “Got him” and I wrestled from my sleeping bag, fumbled in my socks up the fo’c’sle ladder and peered out on deck.

The sea was flat calm, herds of seal were flipping about, bathing and tumbling in the morning light, Mike was poised, with his harpoon, adjusting the tip on it and the Tookak was under way, gently moving forward towards a wounded seal, snuffling and staining the grey sea red. Mike knelt on one knee at the side of the boat, his right arm raised for the strike.

The boat slid by the seal, Mike made a mighty downward thrust, he drove the harpoon hard through the seals shoulder, detached the harpoon shaft and hauled the shining silver body aboard. He hit it hard across the head and laid it so the wound dripped over the gunwhales into the sea. The Eskimos were particular about keeping their boat clean.

In a few seconds the seal was dead.

Mike probed for the harpoon head with his fingers, extracted it, washed it in sea water and prepared the weapon again for the next kill. Under the watchful eye of Pitsolak, the two boys and I took turns at the wheel during the day. The boys sat on the upturned honey bucket with as much sangfroid as the master of a Cunard liner sitting in the captain’s wheelhouse chair and confided to me he wanted to be the captain of a big ship someday.

Once when a breeze sprang up as we passed some ice floes, Pitsolak threw his coat around my shoulders.

When the hunters closed in on the seals, Pitsolak always took over the helm. To get at close quarters with the seals, Mike and Eetuk climbed down into the canoe we had been towing astern and set off in pursuit; Eetuk at the tiller and Mike armed with a rifle and harpoon. To my amazement, as the canoe returned it began to circle the Tookak, Mike stood, braced against a seat and in his hand he carried a cine camera and he filmed our progress down the bay to the point known as Frobisher’s Farthest.

By evening, there were half a dozen seal in the Tookak and Mike directed Pitsolak to steer into an inlet between spectacular, rose coloured mountains. We were to spend the night in the shelter of the cliffs. Our wake rolled behind us in the placid blue sea like the pleats of a great wide skirt. Water slapped the overhang of mushroom shaped ice floes and rattled and chattered into small tunnels through the ice, and a glorious sunset began to blush the sky.

We had a kettleful of tea and then Mike took Pitsolak on an evening excursion, duck hunting, while Eetuk, Isaak and the two boys stayed on board with us.

We cruised deeper into the inlet of Leach Bay, the engine barely turning. All was serene, when Eetuk called out softly.

“Nanook.”

“Polar bear.”

Nanook was a cream furred young bear, out for an evening swim across Leach Bay, and he must have been a quarter of a mile away when Eetuk first saw him.

The boat immediately changed direction, Eetuk handed over the helm to Isaak and loaded his rifle, lining the bear in the telescopic sights. Nanook sensed the danger and tried to escape us by diving under water and changing direction, but he was caught in mid-channel and stood no chance of escape.

The boat began to circle him in decreasing spirals, and Nanook began gulping air and diving faster with the faith of an ostrich.

First his sooty black nose would break the water followed by two coal black eyes and small ears on his long head, he arched his great neck and enormous shoulders and plunged down revealing chubby hindquarters, a stubby tail and big back paws.

I watched fascinated and Rosemary, bestrung with cameras worked away taking colour shots and black, and white photographs as the bear dived and surfaced. The boat circled in and out of light and shade and the exposure differed constantly for her work as we altered direction. The bear was photographed from every angle. We called out, “Hello Nanook,” across the evening air and Eetuk lowered his rifle.

With incredible courtesy, Eetuk asked us through Mosher our young interpreter, if we minded him killing Nanook. He wanted him for supper.

A polar bear is the greatest prize an Eskimo hunter can take, even when it is a sitting duck, so I told Mosher to tell Eetuk to carry on although I felt like a Pontius Pilate. Hunting was Eetuk’s life and there is no room for sentiment in a hunting economy. Hating to see the cornered animal killed, I miserably turned away my head.

One shot rang out and thundered through the high red cliffs of Leach Bay. The bear stopped swimming.

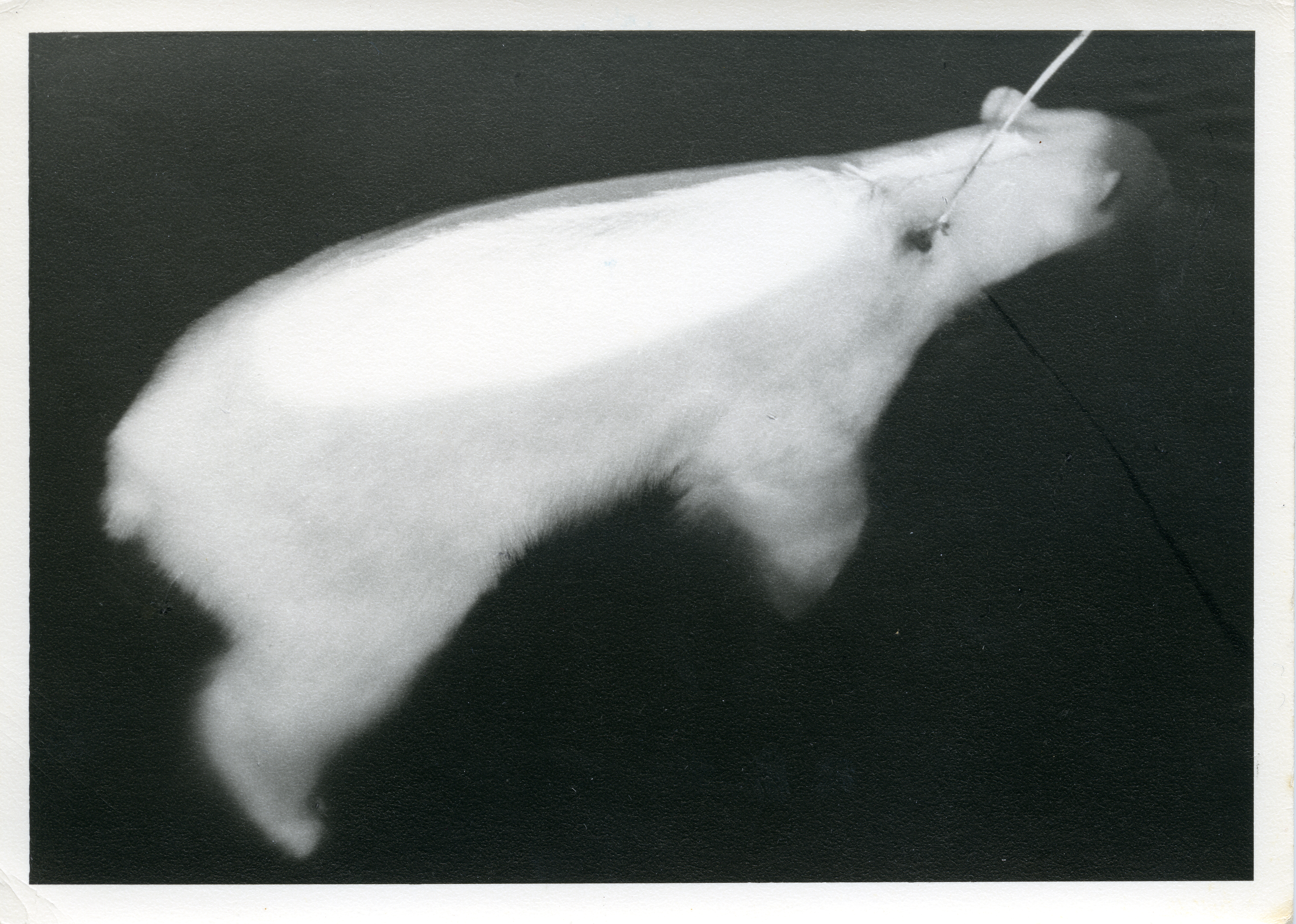

Before the final echo had died, the Tookak was alongside Nanook and Eetuk had harpooned it through the shoulder. His aim had been unerring, his harpoon thrust was clean. The animal was too heavy to be hauled on board, so it was towed alongside the boat to a rocky shelf, where, later, all the hunters helped to skin the carcass and divide the meat.

Eetuk prescribed the way to skin Nanook and drew the first cut from lower jaw, across the underparts to the tail. The second incision was from one fore paw across the chest to the other paw, then the men began to strip the coarse fur coat. Skinned, Nanook looked like a pale old man as he lay sprawled on the wet rocks, his rich fat making the ground slippery to stand on.

That night, sitting on caribou skins in the hold of the Tookak, I tasted a most rare and welcome dish of polar bear, stew. By common assent, Mike was the cook. His recipe was rump of polar bear cut small, salt and pepper to taste and equal quantities of fresh water and sea water.

We sat around, sniffing its aroma as it bubbled on the campstove. By ten o’clock, Mike indicated dinner was ready and sentimentality evaporated as I reached for the salt and pepper. It was a truly communal meal out of a communal pot. We had no plates, no vegetable nor any other culinary accessory and we needed no hors-d’oeuvre for hunger is the sweetest sauce. I stabbed for a piece of meat and speared a morsel on the end of my fork.

It had barely reached my lips when Mike seized my wrist and shook the meat off my fork back into the pot.

I sat frozen, wondering what indiscretion I had committed.

He reached into the steaming pan with his knife and pulled out an enormous piece of bear steak, dotted with lumps of glistening fat, and with a generous courtesy, he impaled it on the end of my fork. Despite my hunger, I was a little wary, but I smiled at him and blinked at the food in front of me. It could never be put back in the pot and diffidently, I nibbled at its edges. I knew I had to eat it all and I wondered if I could.

The second mouthful tasted better than the first and pleasure increased with each bite, and soon I was eating with as much relish as Eetuk who had shot the bear.

Suddenly, the oil lantern used to illuminate the hold fell from its hook and rolled across the floor at my feet. Mike bent down to ensure no fire could start and disturb the meal, then unconcernedly he leaned back against the wall next to me and carried on eating. Too busy to relight the lamp.

The moon began to filter through wispy clouds, and shone pale light through the hatch, illuminating every face that gleamed with grease and gravy. White teeth flashed and bit on a knob of meat held in each left hand, a razor-sharp Eskimo knife slashed and separated each mouthful from the portion remaining in each hunter’s hand. Lips smacked noisily, and with a few chews Nanook’s meat disappeared down eleven hungry throats. Not even the juice was wasted – the gravy was poured into a mug and passed round. Nothing remained of the dinner but a greasy pot.

That night, Rosemary and I slept again in the unheated fo’c’sle and although it was quite cold outside and ice lay near us, I was thoroughly warm.

Mike seldom spoke in English, always preferring to use Eskimo, but the next morning as I climbed out on deck he came to me and said clearly: “You sleep good and warm?”

It was more a statement of fact than a question.

“Yes Mike. I was like toast.”

And then he pointed out his lesson in clear English to make sure I understood: “Sleep well. Polar bear meat make you good and warm. Polar bear meat best to eat.”

He was quite right, I had been as snug as if central heating had been in the Tookak’s fo’c’sle. I thought of the hundreds of Eskimos in Frobisher, subsisting on the pancake bread called bannock, and I imagined how they would have relished the meal I had eaten. Mike had given me a salutary demonstration of the need for good fresh meat in a cold climate.

He turned away to busy himself with the engine, and soon the two boats were heading back to the confluence of Leach Bay and Frobisher Bay, where we were to part company. Rosemary and I were expected back in Frobisher that night, so we were to return with Spyglassee in the whaleboat while Mike went onwards to Hudson Strait to hunt for walrus meat.

We climbed down into Spyglassee’s boat, followed by the two children, Mosher and Sapinak, and Pitsolak. The seals, still unskinned and the polar bear meat, packed in plastic bags was lowered into the bottom of the whaleboat and we began the journey home. As we moved further away from the Tookak, Mike waved urgently and signaled us to return. He circled and moved alongside the Tookak. Mike pulled off his sealskin mittens and threw them down to Mosher, his son. He gave us another seemingly nonchalant goodbye and bent down to his diesel engine.

Mike was almost inscrutable, but not quite.