Chapter 20 ~ A Small Port in a Storm

Getting into Spyglassee’s whaleboat I had the sensation someone was going to shout, “All aboard the Skylark.” It was an open craft without deck or shelter of any kind, but he made it snug for all that through sheer force of personality.

Its engine would have been used for scrap metal in many another place, but his presence contrived to give an air of serene security, and once on board, we soon learned the reason for all the laughter on the whaleboat.

The wind was blowing from the south and the tide was rising as we headed for Frobisher, so we had wind and water helping to scud us along on a navy blue sea. We were making fine headway when suddenly the engine faltered, stuttered and cracked with a report like a cannon shot. Mosesee, the engineer, clawed at his breast, groaned horribly and fell sprawling across the engine housing.

I was stunned at the rapid change in our situation and looked to see who had fired the shot, whereat Mosesee got to his feet with a chuckle that would have made him leading claqueur at a comedy theatre and energetically started to swing the flywheel of the engine. The motor sparked, hesitated and purred into life again.

I said to myself “It’s one of those is it,” and steeled myself for another journey of stops and starts.

While the motor was turning we made rapid progress. When it stopped with the preliminary stutter and explosive crack, the wind’s noise was noticeably stronger each time, but it never deterred Spyglassee and Mosesee from going through the pantomime of being shot to death by the engine.

When in motion, we overtook the heavy ice pans being blown up the bay in the same direction as ourselves. The eroding waves formed overhangs on them as the water slapped and chuckled beneath. I was clad in many layers and cloaked in oilskins, but sitting in the stern of the boat, the following waves, the blowing spray and the rain soon soaked through to my skin.

I felt the first cold touch about my neck, sensed the cold trickle towards my waist, saw the puddles form in my lap and felt them soak through unexpected perforations in my yellow waterproof and seep round to the very bench I was sitting on. Globules of water collected on my Harris tweed socks, massed together and drained into my boots to the soles of my feet. If I kept still the sheet of water enveloping me remained tolerable. If I moved a fraction of an inch inside my clothing, the insulation was shattered and I had to ease myself back on the cold layers about me, warming them with my diminishing body heat.

Dulled and almost immobile, we sat while the hours passed. The two children, Mosher and Sapinak, lay at my feet in the bottom of the boat, curled on caribou skins with an oilskin over them. Mosher pulled his parka hood forward, wrapped his arms; about himself and fell asleep though the rain drummed down incessantly on his face. Almost half the child’s life had been spent in a centrally heated sanatorium, he had slept in clean white sheets, been afforded the best medical attention and given a White man’s “balanced” diet. Yet there he was, back in his historic environment, sweet natured, jolly as a sandboy, learning to be a sailor and a hunter, uncomplaining and soaked to the skin. He was undoubtedly the most courteous child of his age I ever knew and expressed words of kindness that seemed implicit in the actions of almost all the other Eskimos I travelled with.

By mid-day, the wind was much stronger and the waves sometimes broke against the stern. The engine had stopped countless times and Spyglassee roused us into animation by calling it was time for tea and nosed the whaleboat towards a group of islands strung across the bay.

The ice pans were more numerous on their southern shores and forbidding cliffs looked ahead. Breakers crashed against them, reared high and smothered the clifftops in clouds of spray. It looked impossible to land, but Spyglassee was a peerless navigator and knew the channels well.

We rounded the northern spit of a high island, and turned to port across the wind. The boat rolled with a nasty gait, then Spyglassee indicated to Pitsolak at the helm to turn into the gale. As we neared a lee shore, the cliffs backing the tiny beach shielded us from the worst of the wind, but three giant ice floes lay aground in the entrance through the shoals, barring our way.

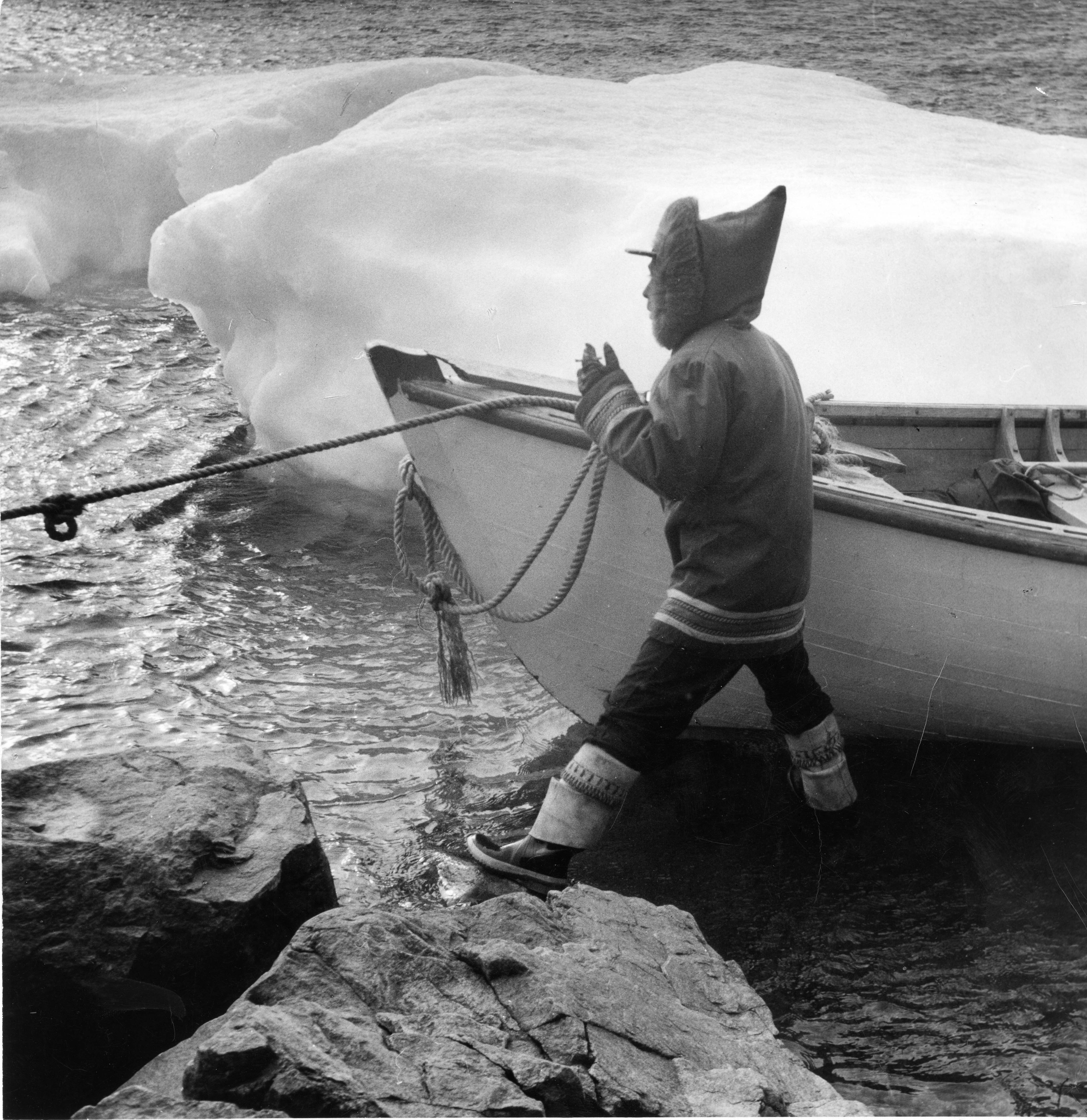

Spyglassee braced himself in the bow and gave a small signal with his left hand, Mosesee eased off the throttle and we wedged our way in against a rocky shelf.

Pitsolak was first ashore with the painter and secured us before he dashed over the rocks to collect fresh water from a stream gushing over the sand. Then, sheltered by a canvas tarpaulin, he lit the camp stove on the boat and we waited with watering mouths until the teakettle boiled. Then he put on a stew pot full of polar bear meat. It had a splendid piquancy and improved in aroma the longer we waited. The fat was soft and succulent and so rich you dared not eat too much. The meat was pale and tender and looked nourishing. We had no forks available and I felt myself going native as I seized a chunk in my fingers, bit a mouthful and made an accurate imputation between my lips and my clutching knuckles. I noted in my journal later in the day that “for this operation, the knife should be sharp.” When lunch was over, Spyglassee said we were to stay the night on the island. For two hours we nursed the boat inch by inch up the rocky channel as the tide filled the gullies about us and gave enough depth to float the whaleboat round the grounded ice floes. Pitsolak and Spyglassee hauled the boat ashore while Mosesee watched. I learned that Mosesee also had heart trouble. He also had had lung resection.

I gathered driftwood from the lee shore, lit a fire under the overhang of the cliff and laid out as many clothes as could be spared. Spyglassee carried the canvas tarpaulin up the beach and the three men built it into a tent, anchored it with rocks from the beach, then with supreme and never to be forgotten courtesy Spyglassee turned to me and said in English: “This is for you.”

The men, he indicated, were to sleep in the boat.

It was time for Rosemary to produce her surprise from the bottom of her kitbag. She hauled out a pup tent made of fine Egyptian cotton. It was little larger than a loaf when it was packed, but it slept two when it was rigged.

Spyglassee had never seen such adequate shelter produced from such a small parcel and did not understand at first that the small package was a “tupik”. He watched us connect the sections of the collapsible tent poles and shake out the tent. The three hunters and the two boys jostled round, suddenly realised what it was and seven pairs of hands pitched the little tent as the mounting wind billowed and cracked the cloth like a dog whip.

I do not know who was the more relieved that we had a tent. The Eskimos who did not have to sleep under a cold wet boat, or ourselves who knew they also were warm and fairly dry under canvas. Even without an anemometer, it was clear the gale had become a hurricane. I scrambled along the beach, bent double to make any headway. At the west side of the island I mounted a low bank overlooking Frobisher Bay and lay face down in the blueberry and Arctic willow. Heavy ice pans lumbered up the bay at a slower pace than the waves and tide. The water smacked into the ice obstructions, seemed to hesitate momentarily then flung itself upwards, was caught by the wind and tossed in a white foam on its way northwards. I was glad to be on dry land. Driftwood lay on the lee shore, so I dropped to the beach and scoured it for fuel as I returned to our camp at the base of the cliff. Although the Eskimos had pitched the tents in the most sheltered place on the island, the wind howled round us like banshees. Anticipating the worst, we rolled the biggest stones we could find to anchor the guy ropes and tent poles. Then we buttressed the anchors. Even so, the wind whistled about us, seeking the merest shred of loose canvas, flapping it slacker until it whipped like gunfire. At five o’clock in the morning, the wind and noise decreased and we fell asleep, worn out, while the sea washed up the beach.

When we finally wakened, Spyglassee considered the sea conditions and the receding tide. We had slept through the time of high tide and the boat was lying only partly in the falling water, so we spent the day on the island.

Pitsolak served morning tea like an inveterate Englishman and we responded by drinking it and teaching his son, Sapinak how to tell the time. With pots of tea brewing and pans of polar bear stew simmering, the Eskimos’ tent had a pleasant picnic air about it. They chattered and talked, finishing their sentences in an upward tone, smiling and laughing a lot with obvious good humour towards each other. The children interpreted for us with shy charm and nobody fretted about time except Mosher, who said: “I hope we get back by Sunday. Then I can go to Sunday school.”

Spyglassee disappeared down the shore and went aboard the boat. When he returned he had a small cardboard attaché case in his hand. He laid it on the sand, opened it and pulled out a mirror and razor. He put the mirror on the lid and proceeded to shave the sparse whiskers on his chin with a pan of cold water, a piece of toilet soap and the safety razor.

When I left the Arctic I found the most frequent question asked me was: “Didn’t you find Eskimos were terribly dirty?” And always came to my mind the memory of dear old Spyglassee offering us his tent on a hurricane swept island and shaving in icy water to keep up appearances as would any former special constable of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Spyglassee’s attache case contained other treasures. He had a bible and a hymn book, both written in syllabics. Mosher and Sapinak seized on the books and spent the afternoon reading hymns and urging Rosemary and me to sing “Jesus loves me this I know” and “Now the Day is over.” It was almost enough to convert an atheist to Christianity.

The rain and wind had stopped by Friday evening and the men went out seal hunting on the evening tide while Mosher wrestled with a razor sharp knife and the vertebrae of Nanook’s lumbar region, preparatory to putting on the dinner pot.

I watched his smooth young face as he took up the bloody mass, poked around at the marrow, clenched it between his teeth and sucked it up. He swallowed it with such relish that I had to envy him his delicacy.

It was the only portion of the polar bear the Eskimos ate raw. The flesh is often infected with the parasite Trichina Spiralis, which results in the deadly disease trichinosis. The same type of worm is sometimes found encapsulated in the flesh of pigs, and unless the meat is thoroughly well cooked to kill the encysted worms, anyone eating infected pork can contract illness.

When the diseased meat of either pig or polar bear is eaten, the capsules enclosing the worms are digested, and the liberated worms burrow their way through the body, causing pain, fever, and if untreated, death can result. Consequently, experience has taught the Eskimos to cook bear meat no matter how keen their appetites or how long they have been hungry and though they will eat seal liver raw, they will not even give the liver of a polar bear to their dogs.

For as George Koneak said – “it’s powerful stuff.”