Chapter 7 ~ First Seal Hunt

As June drew to a close the bonds of ice gripping the Sylvia Grinnell River were sundered with the force of melting snows, and a racing current scoured the channel free. The Arctic char, which had lain dormant all winter on the lake bottoms up river, began their annual journey to the sea, swimming downstream with an easy motion. And so the fishing season began.

Throughout the twenty-four hours of daylight, while the char were running, Eskimos fished from the riverbanks. With my mended fishing rod I tried supplementing our tinned beef with fresh fish. Though I used every kind of lure, I never caught a thing except a catfish close where the river flowed into the bay. On every rock and ice floe near me, the Eskimos hauled in char almost as fast as they threw in their hooks. Rosemary was unwilling to try as she had firm ideas about hurting any kind of creature, and finally I gave up and left the Eskimo fishermen to their spoils. They had more need and far more skill than I.

By the second week in July, the combination of flooding river and pale warmth of the sun had cleared the winter ice from the bottom of the bay and we were told to be ready at short notice to go seal hunting with Spyglassee and Mike.

On Monday, July 11, the weather turned cold and raw. A strong wind toppled the shore ice as the tide crept over the sandy delta. Rosemary spent the day indoors, working in the dark room loaned to her by Mr. Dobbin, while I identified some of the wild flowers we had collected, and placed them between sheets of old Montreal newspapers and laid them aside under mats to press them. During the afternoon a message came to say the seal hunt would start at about nine o’clock the following morning, provided the wind dropped.

On Tuesday morning, Rosemary was up early to scan the sky. The wind had diminished, but the day was grey and wet with drizzle. We dressed in long woolen underwear, ready for a day on the water. Rosemary packed dried fruit, nuts and a stack of sandwiches in my rucksack and after a meagre, hurried breakfast we set off carrying our cameras and recording equipment.

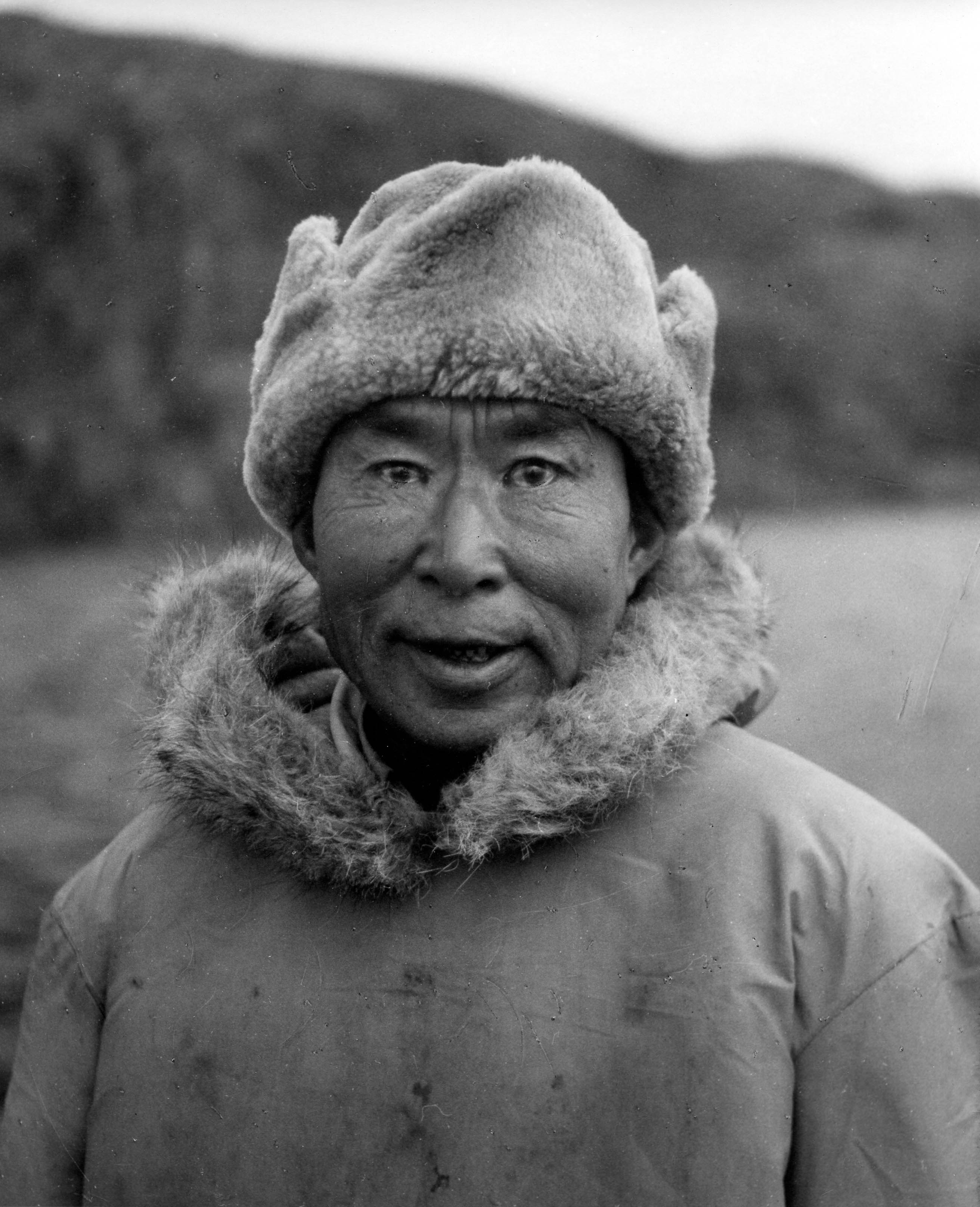

The rain lifted when we arrived on the shore and we could see the Peterhead boat anchored about a mile off, beyond the shore ice. Spyglassee, Mike and Mr. Green were busy ferrying out drums of fuel, harpoons and rifles in an outboard motor canoe. Spyglassee removed his mittens in Eskimo style and smiled as he greeted us with a warm handshake. Mike nodded, still looking inscrutable and carried on loading the canoe, Rosemary unpacked some cameras and went along the shore to take close-ups of the flowers – sea lungwort, Mertensia Maritima, and bellflower, Campanula Rotundifolia.

A sweet-throated snow bunting perched on top of the HBC flagpole and began to sing so loudly that I decided to make a tape recording of his song while waiting for Spyglassee to return in the canoe. I became absorbed in making the tape and added an impromptu script between outbursts of bird song, describing the phenomenal forty-foot tides in Frobisher Bay, among the highest in the world. As I spoke into the microphone, the tide inched forward. The snow bunting started singing again and I reached as high up the flagpole as I could to make certain of a good recording.

Next time I looked round, the beach seemed smaller. Rosemary’s parka was afloat and so was the rucksack with all our food. I dashed in after them, encumbered by the tape recorder, but seized the parka before it went out of reach. The rucksack bobbed uncertainly out to sea then sank in about eighteen inches of water, and I was able to retrieve it with little more than soaking my right sleeve and filling my boots with ice cold water.

The Hudson’s Bay Company had been spring cleaning its stores and the incoming tide had released a pile of rubbish on the beach. Among the bobbing cans were some large plastic bags which I eyed with suspicion and consequently I tossed the food from my rucksack, in amongst the floating refuse. I could see it was going to be a hungry day and I hoped it would not be a long one. Rosemary returned, listened to my explanation and asked with a hungry look, “Did you throw away the nuts too?” And I had to admit everything had been committed to the sea.

It looked as though we were in for a lean time. Mike brought the canoe back to shore and Mr. Green returned from Apex, dressed in high boots, thick trousers, woolen hat and a caribou skin parka. I also could see he was armed with a coffee flask, some tinned meat and one loaf of bread. We distributed our weight in the little boat and Mike steered for Tookak, the name the men had given their new boat. Tookak was Eskimo for the business end of a harpoon, usually made from the ivory of a walrus tusk,

We clambered aboard and a thin shaft of sunlight filtered through the clouds. Mist fingered the steep valleys of Meta Incognita, Mike pumped water from the bilges and Mr. Green went forward to help Spyglassee and the third Eskimo, Isaak, to haul up the anchor. After a few concerted heaves the anchor clattered up, Mike started the engine while Spyglassee took the wheel and Isaak laid out ammunition and new, telescopic sighted rifles on the low roof of the engine house. The stout stem carved a half circle in the tranquil water and we headed down the lonely bay.

The boat was about 40 feet long. She had a tiny foc’sle six feet long, a large hold with a camp stove and there was room for four people to crouch in the “engine room.” The wheel was right abaft and completely unprotected, from the weather, and we towed the canoe astern.

Spyglassee wore a peaked tweed cap beneath the hood of his parka to shield his eyes from the glare. He stood sturdily at the wheel, smiling quietly and always watching the water. Mike and Isaak sat on top of the foc’sle, rifles across their knees and kept a tireless lookout for the seals hour after hour.

The Peterhead boat we were in belonged to the rehab centre and had been built by Eskimos in a small ship building yard at Lake Harbour, a former flourishing camp which had lost most of its people to Iqaluit. The minor ship building industry had been established by the Hudson’s Bay Company with government assistance and it had been run under the direction of a shipwright from Nova Scotia, Joe Thorpe. Tookak was probably the last boat of its size to be built at Lake Harbour and because the population was dwindling so rapidly, the shipwright had left and gone home to Nova Scotia.

Two families had sailed the boat on its maiden voyage along Hudson Strait and up Frobisher Bay the previous autumn to deliver it to the rehab centre before the sea froze. They had carried their dogs and sleds with them and when the snows of winter covered the black mountains of Meta Incognita, they had harnessed their dogs, loaded their komatiks and returned to their winter hunting camp on Baffin’s South Shore, where there were walrus, whale, polar bear and seal to hunt.

Seal hunting from Tookak was an affair of patience and keen eyesight. We cruised steadily down the bay, spreading a broad fan in our wake and we all watched for a seal’s head rising from the water. Nobody spoke very much. Suddenly Mike made a rapid movement, raised his rifle to his shoulders. Spyglassee reduced to half speed and steered in the direction Mike aimed his rifle. The seal’s head looked like a black football on the waves. It gulped down air. Mike fired twice rapidly and it disappeared beneath the surface.

In early summer, seals are thin and in poor condition. If killed by the first shot, they sink quickly and a seal hunter has to move rapidly and accurately if he is to save the animal before it goes out of sight, so he shoots to wound, and it is best hunted from a small, maneuverable boat. When Mike spotted and wounded his second seal, he raced into the canoe we trailed astern, heaved on the starter cord and steered for the quarry. The canoe surged ahead for a few yards and sputtered to a standstill. He tugged repeatedly on the starter but the engine refused to spark, and by the time he had scrambled back on the Tookak, without any evident anger, the seal had disappeared and only a brilliant scarlet stain remained in the water.

Mike saw several seals as the day progressed, but they were too far away to capture and submerged as we moved towards them. He remained impassive and turned to either pump the bilge water or pack grease in cups from the diesel engine and screw them on again. He sat in the canoe for a while, examining the outboard motor and eventually grunted in cryptic English, “Too much oil in gasoline. -Oiled carburetor.” Like most Eskimos Mike had a practical ability which makes them efficient mechanics, and there is the undoubtedly true northern story of the Eskimo who bought a watch when he arrived at Frobisher Bay and took it apart to see what made it tick. When he understood why, by an application of basic logic, he put it together again and it still kept time.

The Eskimos seemed tireless on the water, I wished for extra clothes, and tried not to feel cold. The air grew danker as we moved into leads among ice floes for ice still filled three quarters of bay. Seal hunting, even in July, was a chilling business standing on the deck of a boat. Beads of moisture clung to our clothing then darkened as the damp seeped through the fabric. My apologies to Rosemary for losing our sandwiches were overheard by Mr. Green and he shared out what was left of his food. The mist thickened and rolled about us and rain began to fall heavily.

The seal hunters were having no luck and Spyglassee turned our bow northwards among the turquoise and white ice pans swirling in the grey sea. We were still going at full speed, and as he swerved Tookak round the floes I held on tightly as the boat heeled and rolled beneath my feet.

“What time will we get back Mike?” Mr. Green asked,

Mike pondered, turned his head as though listening and peered into the wall of vapour ahead. It took him almost a minute to decide and he said, “Back at ten.”

I looked at my watch and saw it was six o’clock and took refuge in the foc’sle. The three Eskimos stayed together, soaking wet at the wheel. Mike took over and turned our course ninety degrees to starboard, and a dark shadow loomed through the fog as we skirted a rock.

“You wouldn’t last four minutes if you fell in these waters,” said Mr. Green and for hours I watched the Eskimos peering into the white walls of mist. We passed more islands, mere rocks in the water, each wearing a girdle of ice at high water line. The engine dropped to half speed and we were running in shallow water with waves breaking on some shore.

Mike shut off the engine and we drifted forward, nosing our way into thick fog. The howling of huskies pierced the air and Tookak ran ashore. A boy came out of the fog to meet us. We were at Apex. I looked at my watch and the time was ten o’clock. Mike looked no more than satisfied that his judgement was correct and we tried to thank them for taking us. Spyglassee smiled and nodded and we left them with their empty boat on the shore and we hurried back to Frobisher to our hut. We had locked ourselves out and I climbed head first through a window into the warmth, and I blessed the central heating. We boiled up some tea and started to pack our equipment ready for a plane journey the following day which was to take us four hundred miles southwards to an assignment in Ungava Bay.