Chapter 10 ~ Eskimo Hero

The Eskimo language is spoken from Alaska, across the roof of the world to Greenland, and despite the thousands of miles which separate them, an Alaskan Eskimo would be understood by Eskimos in Greenland if he went there.

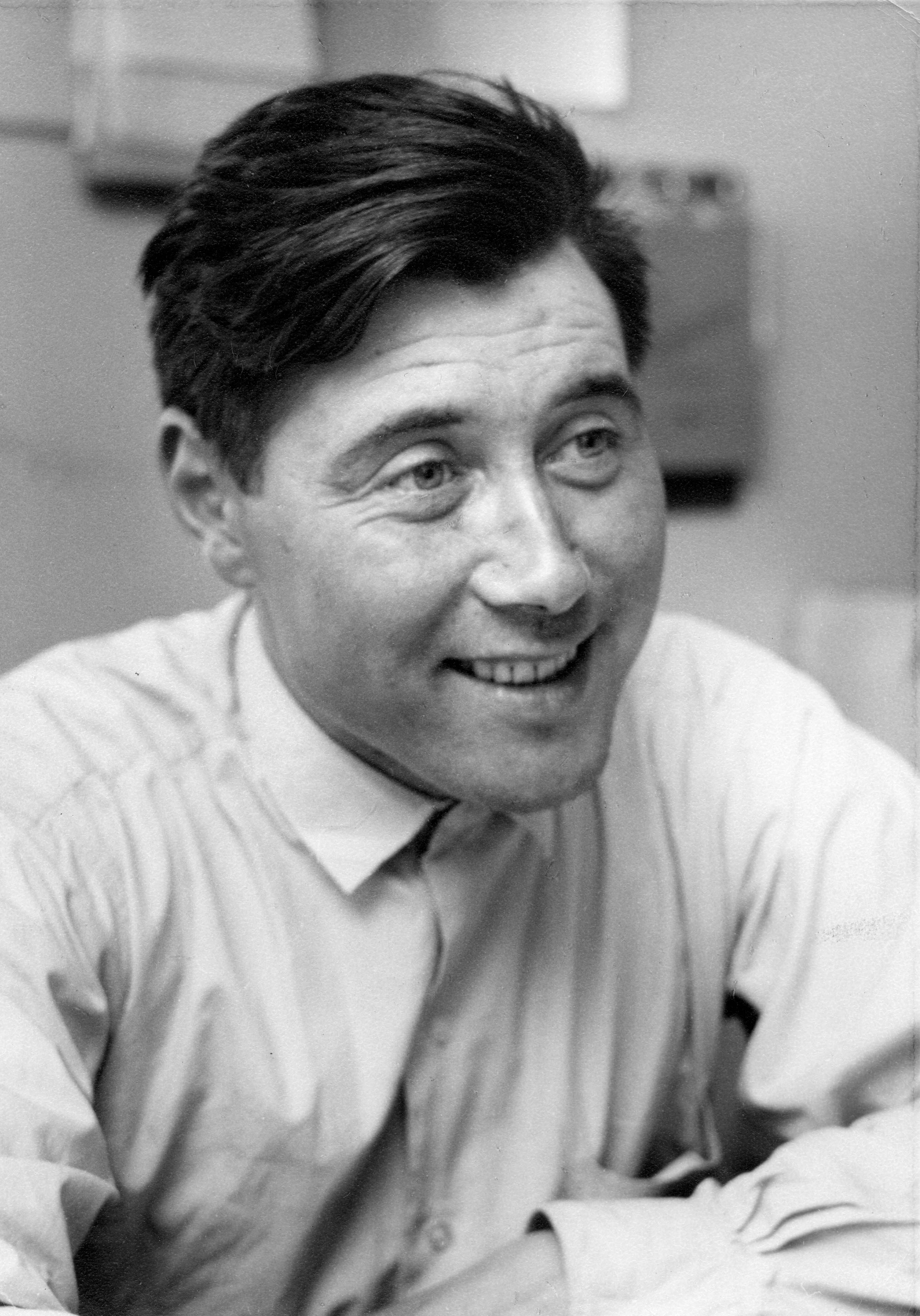

The language is rich and complex, and few non-Eskimos have mastered it. To assist liaison between the Chimo people and the government representative, an interpreter had been appointed. He was George Koneak, aged about thirty, handsome by any standards, with the straight black hair of the northern people and the light coloured eyes of a white man.

George was born at Cape Hopes Advance, the tip of a desolate peninsula on the North West rim of Ungava Bay, where the economy was based on seal hunting. A radio operator who worked at the lonely direction-finding station had taught English to George in return for Eskimo, and the exchange had enriched both their lives. The radio operator later studied at University and returned to the Arctic for some time as a doctor. George grew up to become a clerk in the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, where he was able to put his knowledge of the two languages to good use.

When the government first sent a Northern Service Officer to the area, George acted as an interpreter for him and when the visitor had to travel down the coast, George took him by dog team. A friendly relationship built up between them, and George was offered a job as a civil servant with better prospects than he had ever dreamed of. George accepted the offer and moved to Fort Chimo with his family.

His background made him a unique person. He had lived the complete life of the Eskimo hunter, but he knew English. Usually, if an Eastern Arctic Eskimo speaks English with any fluency, he has lived in a settlement where the white man’s way of life is more familiar to him than a hunter’s semi-nomadic existence.

By happy circumstance, George had combined the best in both worlds. He had a native intelligence and instinct and a capacity for absorbing non-Eskimo skills. Above all he was a man of courage and he is believed to be the first Eskimo to have won an award from the Royal Canadian Humane Association, for the part he played in saving the lives of eight Eskimo children.

Mr. Dodds first told me of the incident and suggested I get George to tell me the story.

It began one day in December, when the temperature stood at forty degrees below zero, Fahrenheit. A dog sled with a lone driver came racing across the snow covered tundra into Fort Chimo. He had travelled without stopping from an Eskimo camp on the west Ungava coast with a message for help.

An epidemic had broken out in one of the camps and medical help was needed immediately. The nursing stations prepared beds to cope with the expected patients, a tracked vehicle, a snowmobile, was borrowed from a local company and the French Canadian driver was dispatched to bring back all the sick people. The driver was accompanied by a priest, by George Koneak and by the Eskimo messenger who had brought in the request for help.

They lost no time reaching the camp and found there were eight children seriously ill. The boys and girls were carried aboard the snowmobile and bedded down on the floor and the driver set back for the nursing station, more than seventy miles to the south.

Because the children were so ill, the men decided to take a short cut across the ice of the estuary of Leaf Bay. It would save time. The weather had been cold for so long that they did not imagine there could be any danger. The ice should have been deeply frozen. But they had not reckoned with the powerful rush of tidal water in the bay, where spring tides are the highest in the world, rising more than sixty feet and attaining a velocity of twelve knots as they sweep through Leaf Passage to the sea.

The forceful rush of water on the outgoing tide that night had weakened the surface ice, and when the snowmobile roared through the Arctic winter darkness, it crashed through the crusty surface and plunged into the fast current beneath.

The driver, the priest and the messenger escaped through the upper hatch, but George Koneak remained with the children, who lay stunned and frightened in sleeping bags on the floor.

The snowmobile had bounced forwards and grounded on rock where it lay shuddering in the forceful waters. Then George began his rescue of the children. One by one, lifted them out and passed them to the men who stood outside. They formed a human chain and quickly got the children to safety on shore.

Death by freezing was close at hand, but George seized a piece of wire and bent the end into a hook. Then he jigged like a fisherman in the black water swirling in the snowmobile. After several attempts, he jigged out the most precious thing in the vehicle. It was a little oil stove.

Still working with presence of mind at top speed, before he took it from the still—warm interior, George pumped it free of water so it would not freeze and burst when it was taken ashore. He reached with his hook again into the rear of the vehicle where the water- was deepest and hauled out a can of stove fuel and some gasoline. Then he grabbed the pilot biscuits floating in the water and the tea kettle and made a dash for the shore.

The snowmobile was later swept away by the current and never seen again.

George then buttoned the children inside the sleeping bags. Two children to a bag for extra body warmth. He put them close together then he ringed the group with gasoline and set fire to it to cut down the temperature. (When the mercury falls below zero, you talk of cutting down, when it becomes warmer.)

While the children lay inside the ring of fire, George searched for snow suitable for the snow blocks required for building a snow house. By some intuitive chance, he had carried his “primitive” snow knife with him when he boarded the snowmobile in Fort Chimo, and by a further stroke of good fortune, George Koneak was almost the only Eskimo in Fort Chimo who was accustomed to building a snow house. He completed the shelter within twenty minutes, and it was typical Eskimo modesty which made George say it was his snow knife which had saved their lives.

“I never knew my snow knife to work so fast. I was wet and shivering but I didn’t notice the cold. My knife was far too busy,” George said as he recounted the event.

He had never built a snow house so quickly and when the last block was put in place the four men and eight children huddled inside to shelter for the remainder of the night. The Primus stove worked, due to George’s foresight, and they were able to boil water for a drink. In the morning, the Eskimo messenger walked off across the snow to see if any Eskimos still remained at a camp he had passed on his first dash by dog sled to Chimo. He found the tents, but only women and children were there. The men had gone hunting on the ice with the dogs and sleds. There was still one sled left however, so he dragged it back to the igloo, the eight children were laid on it and the men hand-hauled it across the snow to the women’s tents.

Time was running short for the sick children, so instead of waiting for the hunters to return with a dog team, the Eskimo messenger set off once again for Fort Chimo. Again he was alone and this time he travelled on foot.

As he neared Chimo, he met a dog team driven by a patrol of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who took him aboard, whipped up the huskies, and sped into the camp. There was only one other snowmobile, but it was mobilised and dispatched to the camp where the seal hunters’ families were sheltering the children.

The children were put aboard once more, and the crowded vehicle turned and raced for Chimo nursing station.

The boys and girls all survived their terrible journey, and their illness. The nurse diagnosed German measles and some weeks later they all were returned safely to their parents.

When George finished his story, I asked him if he had received anything for the part he had played in rescuing the children.

He answered, “No.”

“Didn’t anyone say anything to you George?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied slowly. “The parents. They all said ‘Thank you.’ They were very happy and I was very happy too.”

The official report of the incident had been put away in government files, so when I returned Outside, I wrote to the Royal Canadian Humane Association and told them of George Koneak, and that was how George became the first known Eskimo to receive an award for courage – a courage he and his race take so very much for granted, a requisite for survival in the Arctic and a part of daily life.