Chapter 23 ~ Artists and Spirits

We awoke on our first full day in Cape Dorset to the morning sun straining round a cloud bank. After an hour’s battle it won through and picked out every blade, leaf and stone in all its Autumn brilliance. The date was August 31.

Our tent was pitched on a plateau of velvety tundra above the settlement, and about us, low willow, blueberry and birch leaves were scarlet and yellow, making the lime green caribou moss pale in comparison. A routine was soon devised. First person out of bed lit the camp stove, put on the kettle for morning tea and collected jugs of water from the nearby stream. We took discreet turns to scrub down at the washstand and started each day on a liberal bowlful of Red River Cereal laced with dried apricots, prunes or apple, followed by mugs of steaming coffee and a vitamin tablet.

During our first week living on the hill, the weather was fine and we ate breakfast out of doors sitting in the sun. A small brown lemming lived in a burrow under the rocks and if we sat very quietly in the golden air he would creep towards the crumbs we dropped, but at the least movement he would dart back for cover with the speed of a snapping elastic band.

Day after day, migrating snow geese passed overhead in the morning light. We heard their cries as they lifted from their last Arctic feeding ground nearby, rose into the air, weaving long echelons, pointing the way of their two-thousand-mile journey to the south. By the end of the first week in September the last stragglers had left, and suddenly, summer had gone.

Life’s tempo was geared to the weather. When it was cold and wet, we could do little out of doors, but when the sun shone, we travelled for miles over the hills, climbing the mountains which rose to a thousand feet in pinnacles of pink granite and white fluorspar. My mind and movements became noticeably slower the longer we stayed at Cape Dorset and one day, when I called on Alma Houston, I remarked that I was worried. I had never been in any place where my mind could become so completely blank.

Alma Houston had a personality like a warm lamp in a cold room, she patted her heart and said, “Don’t worry. It all gets stored up in here and comes out later, when you want it.”

So I stopped worrying.

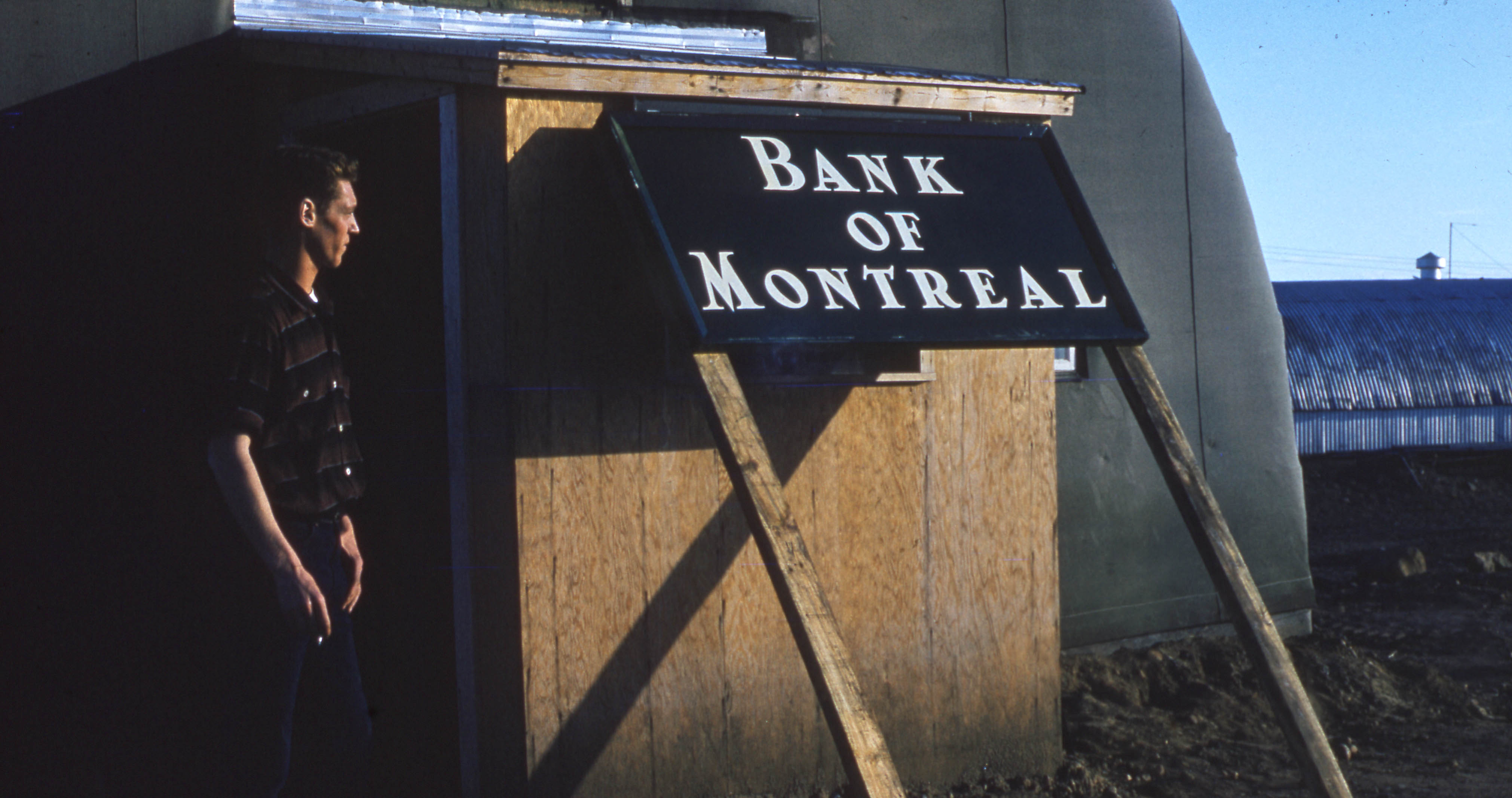

Jim Houston kindly loaned us an oil lamp instead of our candles to light the tent of an evening, and when we called on him in his crowded office hut to arrange the oil supply he was scratching his thatch of dark hair and poring over a thick pile of wage accounts. The accounts were for the Eskimos who had helped to unload cargoes earlier in the summer sealift. He was a victim of Bureaucracy’s Parkinson’s law, inexorably sucked down into paper work at the expense of losing his close personal relationship with the Eskimo people, amongst whom he had lived for twelve years. It was the first year the Cape Dorset people had been paid in cash for their work instead of in credit chits, redeemable in goods at the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post.

Jim Houston told me he had written to the government in the spring asking that cash be sent to the settlement so the men could he paid in dollar bills and coins instead of by chit. The money, five thousand dollars, came almost immediately and was closely followed by a warning from an official of the Hudson’s Bay Company. He wrote that money in the community would cause gambling, drunkenness and prostitution.

Jim Houston laconically told me he wrote back to the man and asked “Are you sure?”

The money began to circulate in Cape Dorset, passing from hand to hand and getting dirtier and dirtier. On some of the paper money I received in change after shopping at the trading post, the engraved picture on the back of a bill had been enlivened by a local artist. He had penned a drawing of hunters, sleds and dog teams racing down the road of an alien countryside.

Despite the ominous forebodings of the HBC, Cape Dorset was still remarkably free of vice after four months’ money handling. Jim Houston was the man who first recognised Eskimo sculpture as a commercial possibility, and it was he who had first organised the export and marketing of them, thus developing the profitable “igloo industry.”

The carvings were originally made as talismans by hunters. The season of the year was reflected in the small charms. When the wild geese returned to the northern breeding grounds the men carved geese of soapstone. If they planned a polar bear hunt, they made a small replica of the animal, just as they did when setting off to hunt whale, seal or caribou.

When the carvings were first marketed Outside, it was difficult to encourage some Eskimos to show their work and offer it for sale. They were shy and their carvings had been made primarily to bring good luck in the hunt. By degrees, they became more confident, gradually making more and larger pieces until some of the work became quite commercialized, ceasing to be real native art and no longer of artistic merit.

In those early days when Jim Houston was helping the people to supplement their credit at the HBC with an income from carvings, he said that he often bought an inferior piece of sculpture from a young hunter who needed encouragement and practice, only to slip it under the sea ice at night. His subterfuge paid off, and there was now many a hunter and trapper supplementing his earnings by selling good carvings and whose earlier work still lay hidden at the bottom of Dorset harbor.

It was a trip to Japan which inspired the first Eskimo prints to be made at Cape Dorset. An artist in his own right, Jim Houston went to the Far East to study print making. On his return, he began its development among the Eskimos. Like many Arctic projects it was slow getting started. Drawing paper, printing paper, inks, pencils and dyes had to be shipped in on the long sea route from the South, and printing techniques had to be learned by the Eskimos.

Contrary to the belief of many people who have not visited Cape Dorset, no attempt was made to influence the Eskimos’ drawing. Those who wanted to try were given paper and pencil and allowed to take the new tools home with them to their tents. When some of the hunters and trappers left for the winter camps, they carried the sheets of paper and pencils on their sleds, far from Dorset and any possible guidance in their choice of subject matter.

In spring when they returned to Dorset, some had forgotten or not bothered to draw pictures, and others produced a surprising collection of pictures illustrating native life, camp scenes, hunting adventures, impressions of Talluliyuk the Sea Goddess, the Eskimo Neptune, and composite forms of animals with the hunters were completely familiar.

They understood the anatomy of animals clearly. No one better than they knew the way a walrus lay on the rocks, or how a seal raised its head out of the water. They knew an animal’s vulnerable parts and positions, and the shape of bone, muscle and sinew, learned at first hand when they cut up a carcass. And no one understood the animals better than the Eskimos, for they had to think like a polar bear when they hunted a polar bear.

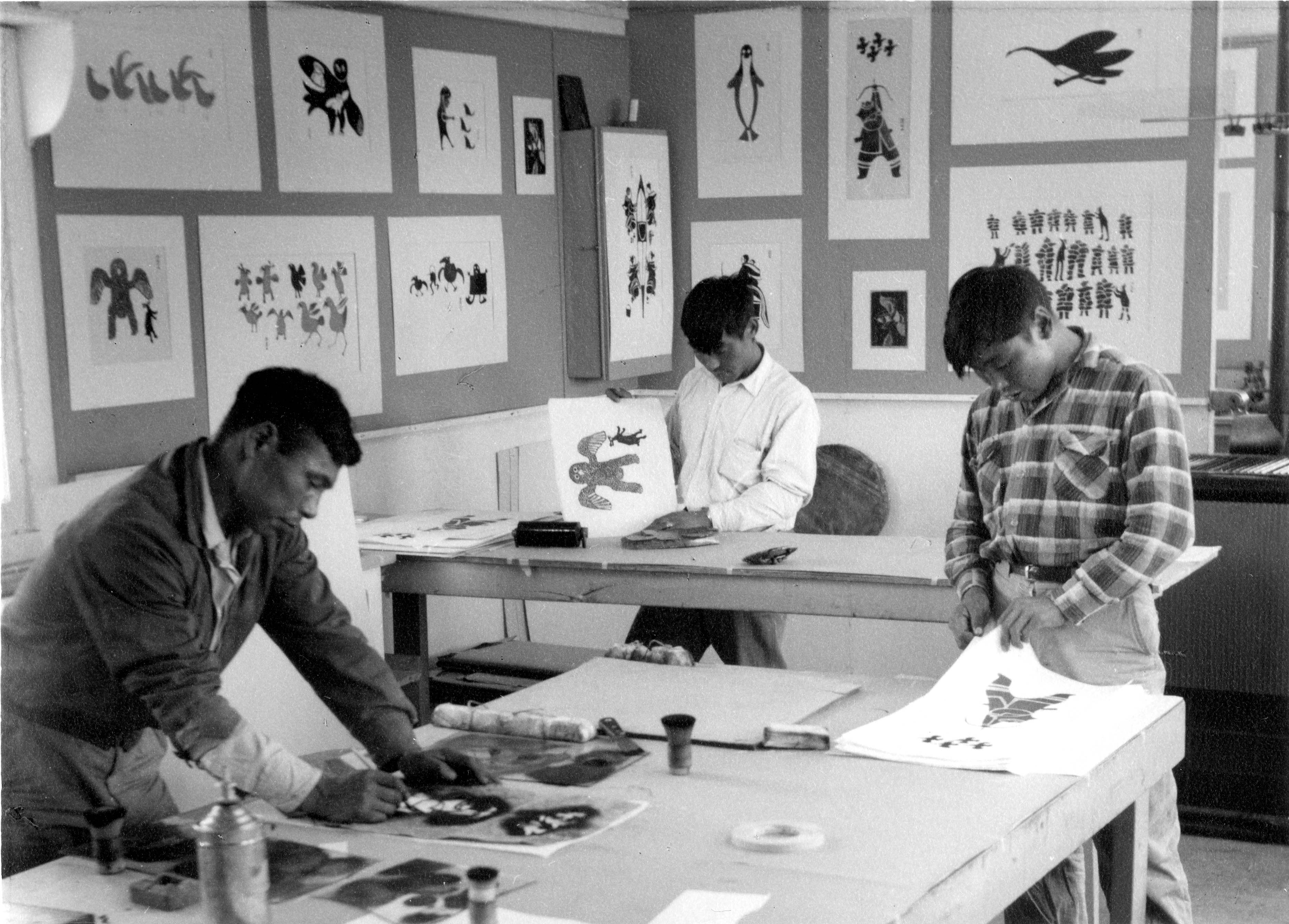

Drawings considered suitable for printing were traced on to either untanned sealskin or on to a smoothed slab of soapstone by either the artists or one of the three Eskimo men who had been trained by Jim Houston as print makers.

If sealskin was used, the outline was cut out to make a stencil and colour applied to the print paper with improvised, shaving-type brushes. If soapstone was used for a rubbed print, the picture was traced on the block, painted clearly with white paint, and carved in low relief. Colour was applied to the block and a paper laid on it and the colour transferred to the paper by rubbing first with the fingers, then with a tampon made from sealskin and finished off with a few strokes from the back of an old metal soup spoon. The number of prints made from each stone cut, or sealskin, was restricted to fifty-two, and the number was strictly adhered to, to preserve the exclusiveness of the prints.

Inferior, smudged prints were torn across and irrevocably destroyed and when the last of a series was made, the sealskin stencil was spoiled or the stone was defaced, filed smooth and used again until it wore too thin to be chiselled any more.

The series of fifty were exported to art distributors Outside. One was kept on file at Cape Dorset and one was assigned to Canada’s National Museum.

The place from which the prints emanated was called “The Art Centre,” but it was merely a small, heated wooden hut where the print makers worked at trestle tables when the weather was not good enough to tempt them seal hunting.

It was recognised by Jim Houston that seal hunting was the most important job of any Eskimo in Cape Dorset, and print making was secondary on such occasions.

Generally, people made their own dyes, using soot from seal oil lamps for black; water and rusty iron stone for yellow and orange and they made blue with lapis lazuli as it was made in England years ago, before aniline dyes were introduced in the mid-Nineteenth Century.

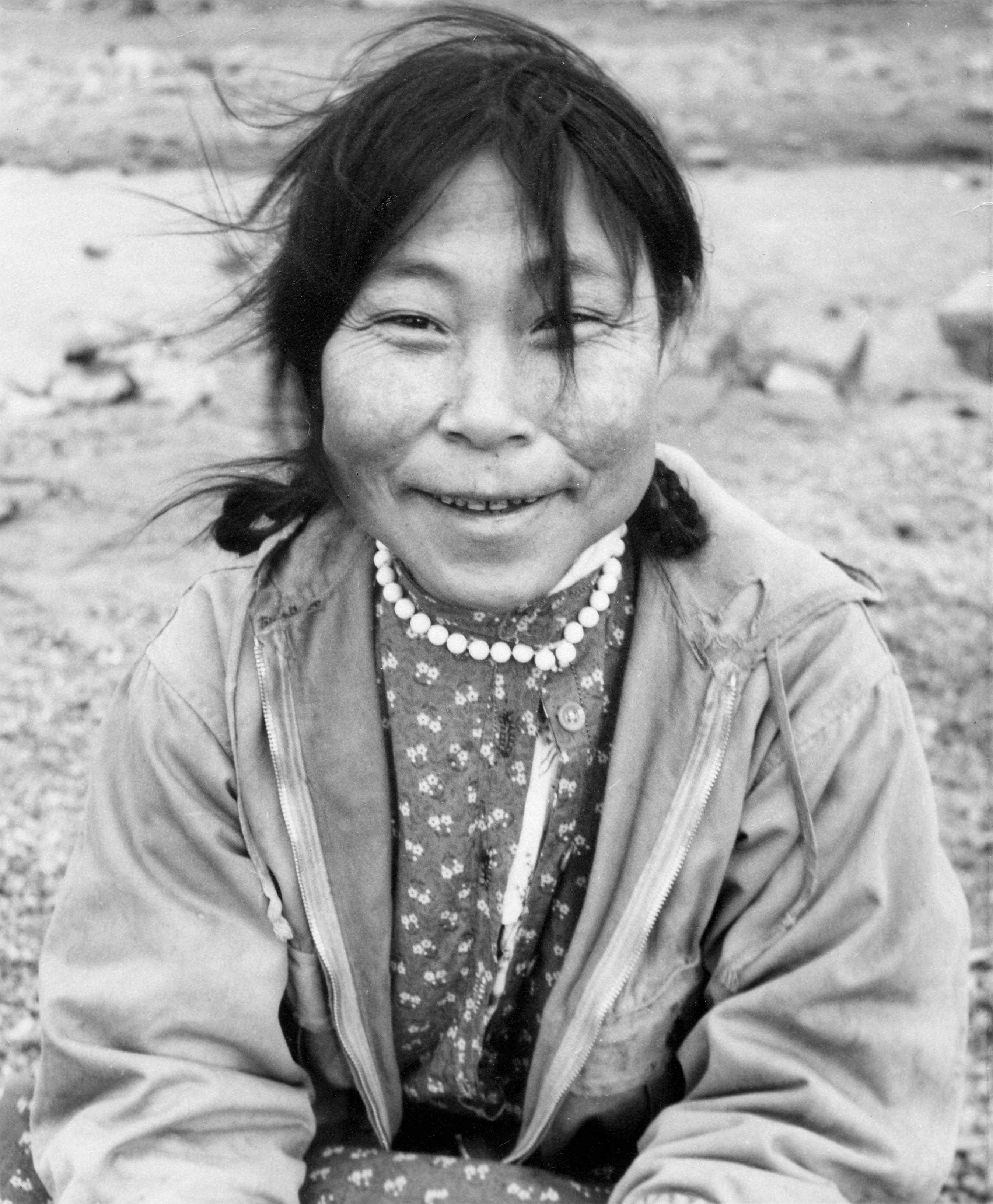

The first Eskimo woman to venture into printing was the gentle Kenojuak Ashevak. Her drawing was sure and her design was distinctively her own. She never used an eraser on her work. When she penciled in a line it was drawn, for all time. She was always at church on Sundays, but her Christianity was evidently imposed on a strong basic belief in the existence of supernatural spirits. Almost everything she drew portrayed some clearly imagined and strange other-world enchantment.

Kenojuak and her friend Sheouak Petaulassie were Dorset’s most talented women artists and their work was exhibited in the United States, in Canada and in Europe. It was quickly bought up by art dealers and by collectors of Eskimo art in plush salons, far from the tents in which both young women lived as the wives of seal hunters in a semi-nomadic existence, bending to tide, tempest and seasons. Neither of them had been to school nor given lessons in drawing. Their work was entirely spontaneous and founded on their beliefs and observations of camp life. They had neither table nor drawing board to work on, but they improvised smooth surfaces from pieces of packing cases and drew on those.

Kenojuak lived in a light and airy tent, so tidy it seemed spacious. She was a good housewife and her few pans, kettles and seal meat pots gleamed with cleanliness, no easy feat when every drop of water had to be carried from lake or stream and heated over her small seal oil lamp.

She was seated on the sleeping platform when we called on her one September afternoon. Sunshine filtered through the tent roof, giving a lovely light as she worked, left handed at a drawing she named “Woman Who Lives in the Sun.”

Now and then she paused and tended the flame of her seal oil lamp with a short blackened stick, pressing down the cotton grass wick into the reservoir of oil if the flame leapt too high, or began to smoke.

Her adopted son, three-year-old Anaco, sat dimpled and smiling, well behaved while her own child, Adlareak, in a woolly sweater and little else, romped over the sleeping platform, showing a tendency to rosy cheeks, even on his bottom and a mongoloid spot at the base of his spine. Sometimes Kenojuak fed Adlareak and sometimes he reached inside her pullover and helped himself. He was fourteen months old. Speaking through an interpreter, she said she knew her prints were to be exhibited in New York, and she knew where New York was.

She would like to have gone to the exhibition, but she expected she would be going with her husband, by dog sled to their camp instead. As we sat there, Rosemary took her photographs and Kenojuak’s husband dashed into the tent, carrying two birds, a sea gull and an eider duck he had shot for their dinner.

He was Johnniebou Towkie, a much taller man than the other Eskimos, a broad six-footer with great shoulders, a kindly face and despite his unusually large physique, he moved over the rocks as swiftly as a lithe youngster. He carried an ivory tipped harpoon and a sealskin line, and stayed long enough to comment on his wife’s drawings of the spirits she saw in everything,

“I think the devil whispers things into her ear,” he said and left the tent.

We went over to visit Sheouak, a wild haired woman in her mid-thirties, small and dainty with an impish smile, a whimsical twinkle and she also had a penchant for drawing devils, spirits and the things of “Satanisee.” Her tent was pitched on a rocky shelf and its door was so small and low that you had to stoop and buckle your knees to scramble in, nearly carrying the door frame with you where your hips wedged in the Eskimo-size entrance.

Inside, the canvas was smoke-blackened with a long kippering from her seal oil lamp, and the tent poles were laced with string and sealskin line over which were thrown duffle socks, sealskin boots, fleece lined knickers, terry towels and mittens.

The only immaculate thing was a clean white folder of drawing paper and cardboard on the sleeping platform. It lay in a welter of caribou sleeping robes, down-stuffed quilts, duffle parkas and clothing. The tent poles were worn smooth with generations of handling and where they had fractured in severe storms they were splinted because long poles of wood are not easily come by in a treeless country. The floor would have horrified a home economist. It was sprinkled with seal meat, blubber, more sealskin boots, cigarette butts, pots of soup, clean kettles, a coffee pot, enamel cups, ulus and tea pots. Poor Sheouak lived in a muddle.

But her delicate prints, drawn in the smoke darkened tent on the rocky beach were among the most coveted of the 1960 series.

The two women artists were good friends and frequently called at each other’s camps. Of the two, Sheouak was the merrier and more boisterous personality. The gentle Kenojuak had been sent to a sanatorium shortly after her marriage, and when she returned five years later, Sheouak, who had six children, gave one of her sons to Kenojuak because Kenojuak had none of her own. (Eskimos love children and the gift of a son was the most generous welcome home present Sheouak could have given. The stigmas of illegitimacy and adoption, which wreck so many lives in a White man’s civilisation do not exist in Eskimo society, where children may change hands but never lack love and affection.)

The boy, Anaco, was full of fun like Sheouak, the mother who had given his birth. Her constant impish humour was evidently his inheritance, and to me, it was quite unforgettable. When Sheouak died in a flu epidemic the winter after we left Cape Dorset, she left behind her a perfect epitaph to an Eskimo woman’s wit. It was a colourful print named “The Pot Spirits,” in which her pans, cups and, kettles were running on strange spindly legs across and out of the picture. Remembering Sheouak’s kippered, untidy tent, it was easy to imagine she had drawn it in amused exasperation after very trying day amidst the comfortable disorder in which she lived.

The finest male artist was Niviaksiak, whose collected drawings were being made into prints while we lived in Cape Dorset. His sudden death, the previous winter was shrouded in mystery and had already given rise to an Arctic legend which was related among the Eskimos and to me. It was said to be a true hunter’s tale.

Niviaksiak was highly thought of among his people. He was a tireless and a successful hunter. He was a born leader and he was a fine sculptor. When a documentary film was made about the significance of carving in an Eskimo hunter’s life, the handsome Niviaksiak and his family were chosen as the players in the film.

When filming began, he chose to carve Nanook the polar bear as subject matter. When the art centre opened and the print making began, he drew wonderful studies of polar bears and it was said he became so obsessed with them that he made carvings and drawings of them almost exclusively.

The winter before our arrival in Cape Dorset, Niviaksiak set off by boat for his winter camp. Snow was already lying on the land. The weather was bad, and when the story of his sudden death was recounted later, it was suggested that bad weather may have had something to do with his death.

Two of the hunters in his party became lost in a storm. Niviaksiak set out to search for their canoe without stopping to sleep. He found the missing men on an island and took them aboard his boat. They did net stop to rest but carried on to the winter camp. They went ashore and almost at once came across the fresh tracks of a polar bear, and Niviaksiak led the immediate hunt. The trail was well defined and easy to follow, and when they came upon the polar bear, Niviaksiak, being the best hunter, was acceded the right to shoot first. He stopped, faced the bear, raised his rifle to his shoulder and put his finger to the trigger. Before he could squeeze the trigger, he fell down dead. And the hunters who were with him said the polar bear and its tracks immediately disappeared. It took Niviaksiak’s spirit with it.

Niviaksiak was buried and the party returned with the bereaved family to Cape Dorset. The settlement was shocked by the news and in case there had been foul play an autopsy was ordered and Niviaksiak’s body was recovered, preserved intact by the cold. An Englishman working at the nursing station said he could find no apparent cause of death. There was no evidence of disease nor of injury. He told me it might have been an obscure attack of trichinosis although there had been no sign that he could find.

The Eskimo people of Cape Dorset were sage about the matter and nodded their heads wisely. Had they not already said, Niviaksiak’s spirit had gone with the polar bear.

I have a print of Niviaksiak’s. It is, of course, of polar bears, hungry and searching the tundra for who knows what.