Chapter 27 ~ Is there a Mechanic in the Camp?

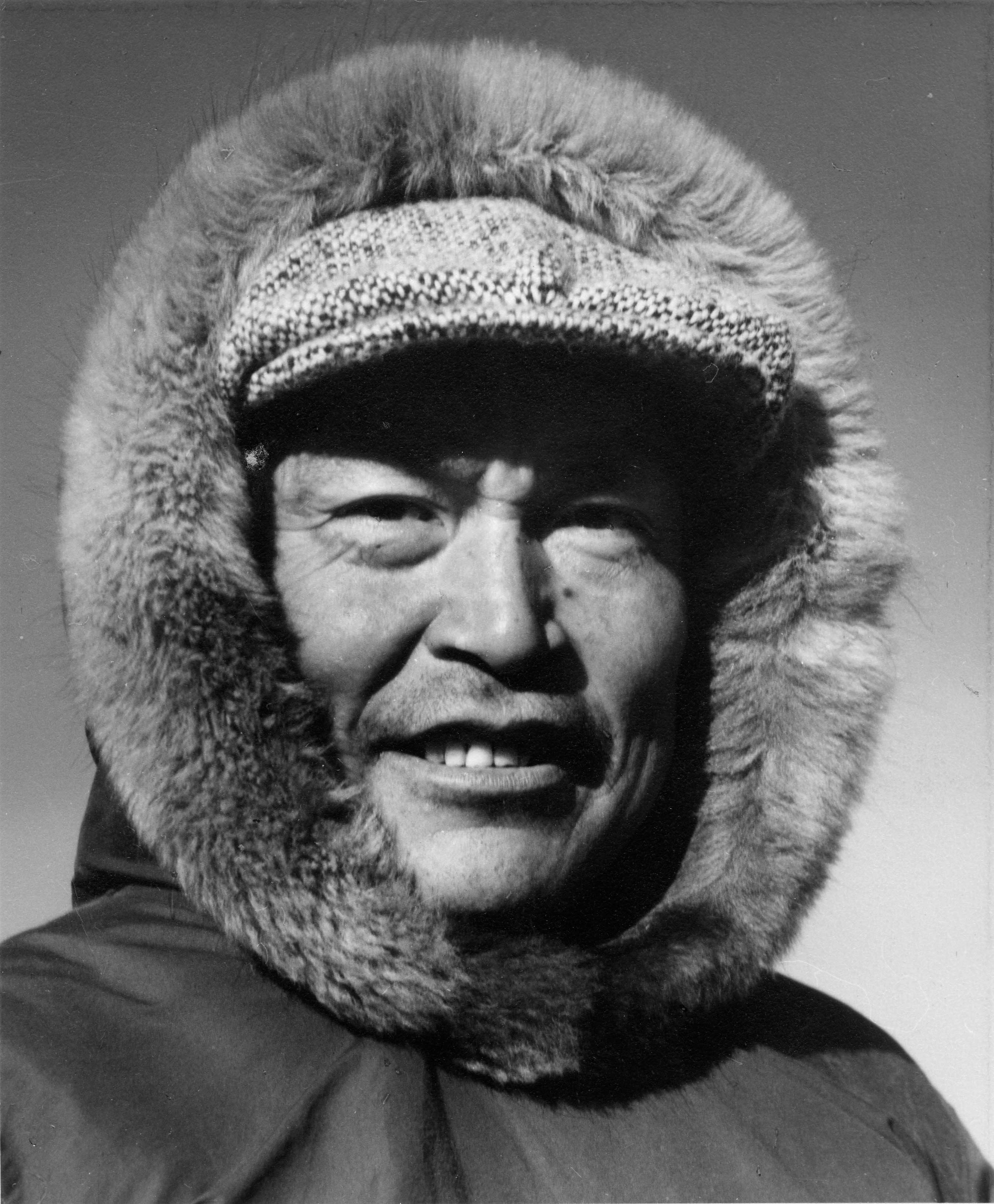

Soon after our arrival in West Baffin Island, we developed a friendship with an Eskimo named Oshowetuk. The relationship was sparked off by his cavalier attitude when one of the journalists gave him explicit and loud instructions as we set off on a seal hunt from the luxury camp.

Oshowetuk was on light duties through Jim Houston’s insistence, because Oshowetuk had recently returned from hospital where he had had resection of both lungs, and like most Eskimos he was the type of man who worked to the limit of his strength, and in his case that would be a dangerous thing to do.

One of his light duties was to take charge of a whaleboat on the seal hunt. Food and flasks of hot soup were loaded into the larger Peterhead boat, which had a cabin for the comfort and protection of its passengers. One of the passengers, a hustling American photographer ordered Oshowetuk to follow the Peterhead closely and to go alongside when signalled to do so.

Rosemary and I were in Oshowetuk’s open boat, and we watched him listen patiently to the photographer and dutifully set course, following the Peterhead wake. It was a poor position if Oshowetuk wanted to get any seal for himself.

A rendezvous had been arranged for mid-day, by which time the rain was dousing us, and Oshowetuk was again told to keep as close as his boat would permit. He was to be ready to take the photographer aboard as soon as a seal was shot, and we were to keep out of his way while he took action shots.

It was plain to see Oshowetuk would not be hauling any seals aboard his boat if he did everything he was told, so when the stout Peterhead bucked into a head wind, squalls of rain and the open sea, he blandly turned his helm in the opposite direction and steered for the coast with his gaze fixed on a flock of eider ducks.

If the Eskimos have proverbs, then they surely have one: “There are none so deaf as those who won’t hear,” and the broad smile on Oshowetuk’s face as he later lifted aboard his bag of eider ducks was too bland to be innocent.

Although the co-operative craft centre had many carvings for sale I wanted one only from an Eskimo I knew, so I went to Oshowetuk and asked him in manual English if he would make me a carving. I wanted it small enough to hold in my hands, and I left the subject matter to him.

A few days later he approached me with a piece of rag in his hand and a broad smile on his face mixed with a certain self consciousness. He dropped the rag into my palm and I opened it to reveal a smooth green soapstone carving of a bird, more perfectly finished than any carving I had seen.

The pleasure on my face was plain for him to read, and he wrinkled up his nose as though to say: “It’s a poor thing. Anyone could do better than that.”

His modesty was typically Eskimo. I learned afterwards that the highest price ever paid for an Eskimo carving was for a piece of Oshowetuk’s work. It depicted a woman and child and it passed through several hands before it brought the lofty price of one thousand dollars and found a niche in a New York museum.

Oshowetuk, the carver, had been paid ten dollars for it. The profit, of course, had gone to the dealers.

For his carving of a bird, I gave Oshowetuk a box of ammunition with which he seemed well pleased, and I reasoned if it were well expended, it would provide him with some meat, blubber oil and clothing for the winter.

Ammunition and rifles were a heavy and constant expense to Eskimos, but in Cape Dorset, the men had been given a rare opportunity to take advantage, unknowingly, of the White man’s “cold war nerves.” The Eskimos could not appreciate the full significance of what was expected of them, but they had been supplied with rifles and ammunition and put in the front line along with the billion-dollar Distant Early Warning bases in the Arctic. If ever North America were invaded, the enemy would first have to reckon with the West Baffin Militia.

The militia were crack Eskimo marksmen, raggedy but formidable, undisciplined but sturdily individualistic. If ever they were called upon to fight, they would probably give a good account of themselves, but unless the Russian Communisticos labelled themselves as enemies or announced their arrival with volley of telling shots, they were likely to be greeted by Eskimos with sealskins to trade, carvings to sell and promises of an Eskimo dansee in the school house to celebrate the visit.

Eskimos are sociable people and liable to treat strangers as friends whether they be French speaking priests, English speaking traders, American speaking airmen or Russian speaking Communisticos. Meanwhile the rifles and ammunition were not allowed to idle and were useful for seal hunting.

Dansees, or dances were held fairly regularly during the summer. The word would spread like wildfire across the tundra, and some child would come dashing to our tent calling, “Dansee, Dansee,” and caper off over the hummocks and rocks to the next tent, full of joy and excitement. It was the signal in Eskimo and English which heralded the gayest evenings we spent in Cape Dorset. The entertainment was held in the schoolhouse and was usually preceded by a show of films from Canada’s National Film Board. The most frequently shown was “The Living Stone,” starring Niviaksiak, the man whose spirit went with the polar bear, and his family. The crowd of “extras” still lived at Cape Dorset and greeted their own images on the screen with cries of “Eee.” At Niviaksiak’s appearance the people would murmur in low voices and his widow, unable to resist watching, would cry softly as Niviaksiak, lifesize, robust, skilled in hunting and so real in colour film appeared on the screen almost close enough to touch. We all squatted on the green linoleum floor to watch the films, massed so closely that we held each other upright, hot and steamy and full of sealskin smells.

When the projector was cleared away, the dance began and the schoolroom came to ebullient life. Dancing was not limited to the youthful. Men and women, children and the aged joined in the marathon shuffles. The music was provided by an accordion played either by Udjualuk, the luxury camp waiter, or by Ageak, the wife of Pitsolak the trapper.

We all doffed our parkas and sweaters. The women wore blouses and skirts over their slacks, and the men contrived in some impossible fashion to wear uncreased, spotless white shirts although I never saw an iron or an ironing board in any of the tents.

The dances seldom began before eleven o’clock at night and they went on until two in the morning – or even later. My first Eskimo partner was a round-cheeked fellow of eleven years named Hatsiak. He was pushed towards me, his hands stuck in his pockets, grinning until his eyes twinkled right out of sight, and presented himself, hat still on the back of his head, for the first measure.

Eskimo dances are a conglomerate of Scottish reels, English country dancing and American square dancing, and while they last, they are far lengthier than three of their source dances put together. Rosemary declined the initial gambol round the floor, saying “I’ll watch one first.”

An hour later, she was still watching as we trotted and shuffled, jigged and reeled to and fro, round and round, while Ageak, the accordionist, flashed her fingers up and down the keyboard, her parka hood slipping lower and lower over one shoulder, her eyes our eyes fixed on our kamiks, and our sweat pouring out in the stifling atmosphere.

Kanangihak, president of the co-operative was obliged to display more agility than the other men, and did so. He leaped higher and higher with a wild abandon, yet organised the routine for the rest of us as the dance progressed.

I was pulled through the complex figures as an example, then everyone joined in and I went through them again. The music went on non-stop, and my breathing became more and more laboured as clouds of green dust rose from the linoleum on the floor. It wafted higher and higher until our faces and hair were rimed with a choking green fog. When Ageak finally squeezed the last splendid note from her green accordion, we dashed outside into the frosty night air where the wind blew chill and rapidly closed every open pore.

Racking coughs filled the air, the darkness was studded with the small red glows of burning cigarettes which throw a ghastly light on each smoker’s green face, and when we were all thoroughly chilled enough to face the next dance, we filed back into the schoolroom.

Some of the men were extremely handsome and graceful as they danced. Divested of their bulky clothing they appeared lithe and tireless. Even Simonee, the catechist, lost his solemnity as he step danced and waved his arms over his head in an ecstasy of rhythm, each time the accordionist burst into a fresh version of the same tune. For me, the dances always ended too soon though they were harder exercise than a day in the hills, and they always necessitated a large laundry and a vigorous hair wash the following day.

The arrival of a ship was often the excuse for holding an extra dance, and towards the end of September, there were two ships which justified celebration. One was an icebreaker on its maiden voyage, and the other was a vessel which called to collect a cargo of empty oil drums. In Cape Dorset, as in many other Arctic settlements, the presence of man was indicated by a litter of old tin cans and empty oil drums. The drums were found in every pocket of non-Eskimo civilization because oil was used by White men for cooking, transportation and generating electricity.

The sudden appearance of a helicopter in front of Jim Houston’s house on September 27 brought work to a standstill everywhere in Cape Dorset. The strange machine, yellow and plastic-bubbled, hovering slowly in the sky drew people to it like wasps to a jam pot.

The pilot said he was from the ice breaker John A. MacDonald, a deep draught ship, which the captain prudently kept at anchor far outside the harbor. She was on her maiden voyage seeking ice in Foxe Basin to practice in, and iron out wrinkles prior to her work in the St. Lawrence in the coming winter.

Hundred mile an hour winds in Hudson Strait during the previous few days had given the crew some anxious moments, even though the ship was powered with engines generating fifteen thousand horse power, and the hospitable captain sent an invitation to anyone on shore to inspect his ship if they cared to go out.

Accordingly in best, locally made parkas, we presented ourselves in the queue of would be passengers standing before the two helicopters on September 28.

The settlement developed into a turmoil.

The people on board ship wanted to be ferried ashore. The people on shore wanted to get aboard so there was busy two-way traffic. Accommodation on a helicopter was restricted to one passenger and one pilot per trip, so the Eskimos boarded their own boats and swarmed out to the ice breaker.

We were given the customary tour, which included the engine room, at which point, Jim Houston asked if the Eskimos could come too. Neither the Eskimos nor ourselves had seen such an engine room before. It looked like a tiled swimming pool, gleaming, clean, fresh with white paint and a spotless floor. Nine great engines nestled in a complex of vari-coloured pipes, taps, tanks and catwalks,

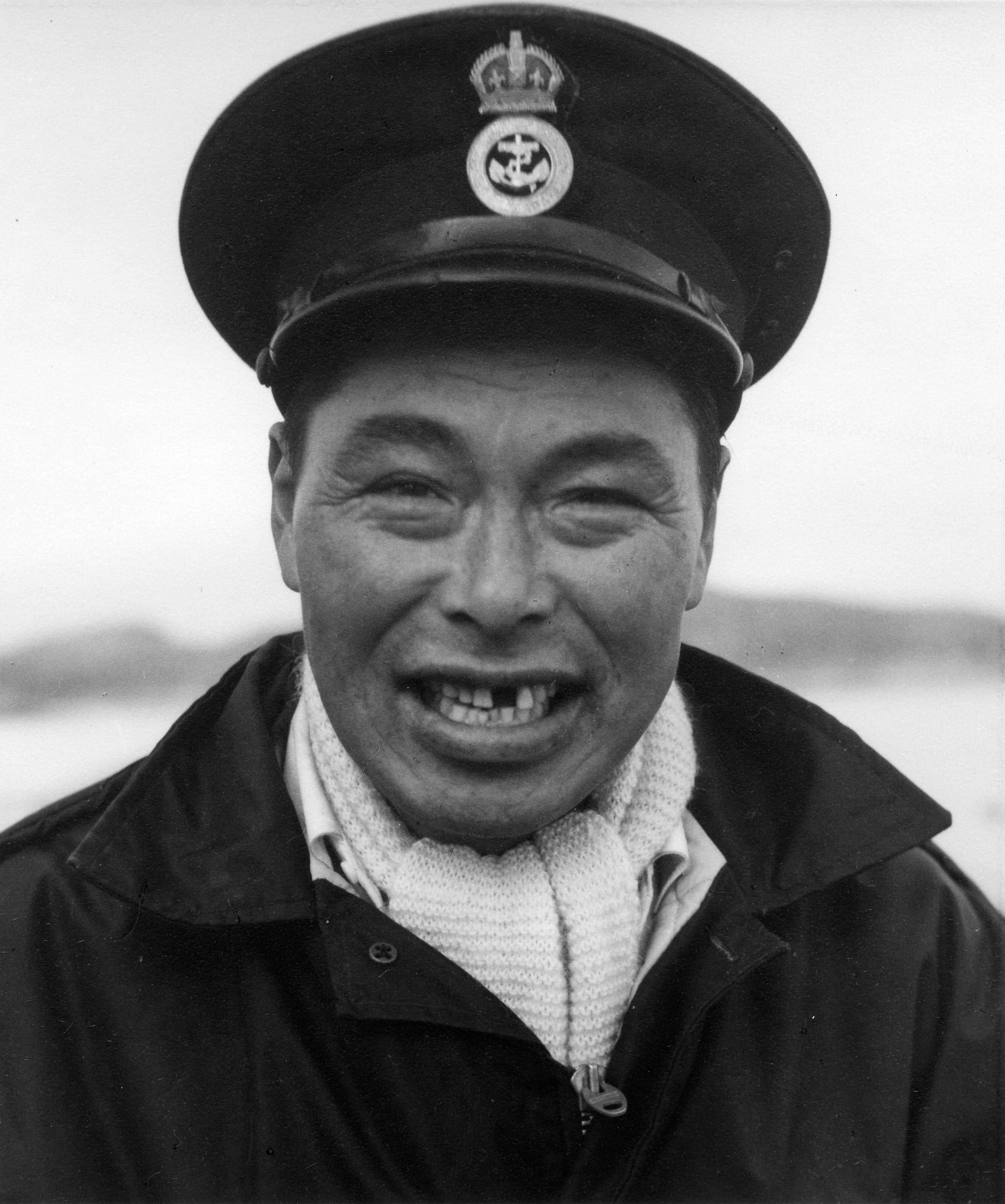

Pudlat, an Eskimo who had his own diesel powered Peterhead, gazed in wonderment, turned to Jim Houston and said, “When I think about the man who designed this engine room, I know my thinking is on the level of a dog.”

When the time came to go home, the ship was rising and falling in the winds of a gathering storm, and the helicopters were grounded. We then turned to the Eskimos in their boats to take us home. A Peterhead tied alongside, slopped, rose, fell, hesitated in the troughs and rolled up again as though the sea were breathing. As it came out of the blackness below, the cabin roof, painted white, glistened in the great ship’s deck lights. We waited near a hatch in the ship’s side ready for our turn to jump down. As each person poised on the narrow ledge of the hatch, there was a shout of “Now.” I was last to jump and waited for the white roof of the little cabin to come into view from the shadows.

Someone said to me, “Don’t jump when they tell you to. Use your own judgement but be sure you don’t go until it reaches the top of the swell.”

Up came the Peterhead, she hovered on the crest of the wave and I plunged down into the dark. An Eskimo caught me and we fell flat on the roof as the engine kicked into action and the Eskimo helmsman steered into the darkness for the shore.

Cloud obscured the noon and stars. Pudlat leaned forward trying to see through the gloom. We must have passed the cape closely, for soon the glimmer of a lighted tent slid into view, glowing like an opal as the wind buffeted the canvas, and soon we were jumping into the shallows and back on the beach.

Hand lamps began to stab the shadows and a line of Eskimos started to gather at the landing place, ready to unload cargo from the ice breaker on the three o’clock tide. They chatted cheerfully together the pointed hoods of their parkas pulled up against the cold night air.

I called out, “Aksuni,” and stumbled up the shore, home to bed. The time was nearly two o’clock.

Pudlat’s remark in the ice-breaker’s engine room stayed in my mind for several days. Of all the visitors on the ship, he probably knew more than any other about diesel engines built on a small scale, but he had felt the most humble.

Within a few days another ship arrived.

The captain came ashore and said he had a liberty boat on deck but it was out of commission. It had an outboard motor and none of his seven engineers had been able to mend it. He had heard Eskimos were wizards at fixing such things. Was there an Eskimo mechanic in Dorset who could look at it?

He was assured there was, and Pudlat was sent out to mend the motor. In a couple of hours he had succeeded where qualified engineers had failed and the captain left Cape Dorset with his regard for the Eskimos’ mechanical ability higher, and more justified than ever.